‘None of the faces wore masks – fear and hope, sadness and joy were etched on all the faces.’

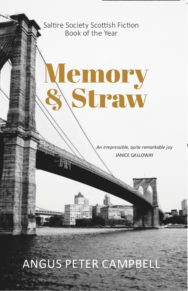

Extract from Memory and Straw

by Angus Peter Campbell

Published by Luath Press

Extract from Chapter 1

The clearest lesson I learned during my research was that features on faces are earned, not given. The age lines, the wrinkles, the curve of the mouth, the light – or darkness – in the eyes. These are the consequences of lived lives, not just the DNA. Hurt, pain and joy experienced are all etched there, as if Rembrandt had suddenly caught the moment when joy or sorrow had called.

I stripped naked and looked at myself in the mirror: the slight middle-aged paunch, the stoop of the shoulders, the face that reminded me of a boy I knew once upon a time.

I probably broke some unwritten rule that you never complicate your research with your personal life, but one day as I was idling at the computer I entered my father and my mother’s name, and the day disappeared leafing through their history. Or at least the history that was recorded there, for like all histories, most lay unrecorded. Like those gaps which Emma saw between the leaves, I suppose.

The Internet is such a recent phenomenon, but nevertheless it has already harvested the work of centuries, so it wasn’t that difficult to scour genealogical and historic sites. The photographs were particularly fascinating: the further back I went the more difficult it was, of course, to find images of my own ancestors, but there were so many historical society sites that it was easy enough to get a sense of the times and places they lived in.

Old men with beards and old women with long black skirts outside little stone houses. Sometimes children playing in black and white, with toy wooden boats or prams. Horses and dogs and carts carrying luggage. Hundreds of faces looking down as the ship left the quay. I showed some of the material to Emma that evening. She didn’t seem greatly interested.

‘Isn’t that what people of a certain age do for a hobby? Start finding their roots?’

‘Well, I never really fancied stamp-collecting.’

I told her a bit about my family tree.

‘You should go to a séance. You could meet them there,’ she said.

What fascinated me immediately were the objects my ancestors had. Ploughs and hand-made saws, clay pots and spindles: things you could see in such fine detail once you digitised the old photographs. Sometime later, on one of Grandfather Magnus’s shelves I found a family photograph of my great-grandmother’s cottage with a bogle leaning against the thatched roof. The bogle was the slim stem of a dead fir, devoid of branches except at the top which was dressed, like a scarecrow, with a white cap and an old jacket. It was set on the ground leaning against the wall and roof overnight, and shifted every morning from one side of the doorway to the other to protect the house and the inmates from harm by the witch.

It was magic. Images were totems which brought blessings or curses. You could sail to success or starvation. I studied the photograph of the people on the emigrant ship for ages. There were of all ages, from babes on the breast to old women in shawls. None of the faces wore masks – fear and hope, sadness and joy were etched on all the faces. I realised that making masks for care work was essentially about tracing these emotions into the contours. The more I understood these emotions, the more effective these masks would be. More people would buy and use them.

I decided to make a test case of myself. To discover how my face worked – what had left it the shape it was, with all the anxieties and hopes that made it more than a fixed mask. The face that I was, beyond DNA, uniquely sprung from all the faces that had been. I travelled. Read. Remembered. Visited ruins and homes. Talked to relatives. Found Grampa’s notes in his old shed, studied the local papers in the Inverness Archive Library, met Ruairidh on the old bridge that takes you to Tomnahurich. Borrowed, plagiarised, and invented things.

‘Will you come with me?’ I asked Emma. But she had her reasons.

‘I’m working on a new composition. And there’s a deadline, Gav. You know that.’

‘The real answer is that you don’t want to go.’

These are the stories I rescued out of the infinity that opened up before me, beginning with my great-great-grandmother, Elizabeth.

Memory and Straw by Angus Peter Campbell is published by Luath Press. The paperback edition is out in July 2018 priced £8.99.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

Memory and Straw

Memory and Straw

‘None of the faces wore masks – fear and hope, sadness and joy were etched on all the faces.’