‘What I love about Harris’s novels is the way that they take the uncertainties we all have about the present and plonk them down again in that other, usually more certain country (because we know what happened) of the past.’

For some reason David Robinson had never read any Jane Harris books until recently. Now having read and enjoyed them all he urges everyone else to do the same.

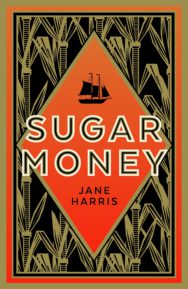

David Robinson Reviews: Sugar Money

By Jane Harris

Published by Faber & Faber

Every newspaper books editor makes mistakes. Even if they don’t always admit it, there is always some writer they feel guilty about, whom they ought to have read but never did. Maybe on the day the press release arrived making stonking claims for a debut novel they subsequently ignored, they were feeling just a little bit jaded. Perhaps they had seen the balloons of hype burst too many times, all those hundreds of books that never came close to matching their publishers’ promises. It happens.

In the first 15 years of this century, when I was The Scotsman’s books editor, I probably interviewed, reviewed or at least read most of Scotland’s best writers. Jane Harris, for no good reason, never made that list. I made sure that we reviewed her books, but I never read any of them. Now that I’ve just finished reading all of them, I’m feeling very guilty indeed, because she clearly is the reigning queen of Scottish historical fiction.

So let me, not just as a penance, but because there may still be some benighted souls out there who still haven’t read a Jane Harris novel, try to back up that claim.

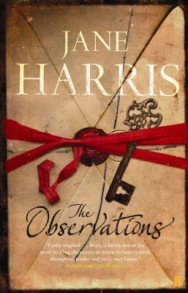

If you start reading Harris’s debut novel, The Observations, you realise how quickly her multiple narrative hooks sink in. In the early 19th century, a 15-year-old girl in a bright yellow frock with white satin bows is walking to Edinburgh from Glasgow, trying and failing to shake off a randy young Highlander, when she sees two policemen on horseback riding towards her, and decides to take a side road signposted to “Castle Haivers”. Maybe they’ll have a job for me, she thinks, and indeed there is, working as a maid for the beautiful English mistress of the house, who makes it a condition of employment that every day she must keep a record of her thoughts and deeds.

The maid is Bessie Buckley, and she is irresistible. When the judges for the 2006 Orange Prize put The Observations on their shortlist, they probably did so because they’d never come across such a thoughtfully brassy, and irreverent ingenue. And of course they hadn’t, because those adjectives, which are usually antonyms, can only apply to a fully three-dimensional character. These are rarer than they ought to be, but Harris seems to be able to turn them out at will.

Look again at the set-up. Why the yellow frock with white satin bows? What is Bessie running away from? Why is she avoiding the police? Will Castle Haivers be a Scottish Gormenghast? Maybe the randy Highlander is there for comic effect, but surely Bessie’s relationship with her new home’s beautiful chatelaine is different? All of these are questions that make the reader keep turning the pages, but as they do, still deeper questions emerge. Is this a love story, or something more complicated? Isn’t it also about writing itself, and how those observations about her own life that Bessie is tasked with producing, can never tell a true story?

What I love about Harris’s novels is the way that they take the uncertainties we all have about the present and plonk them down again in that other, usually more certain country (because we know what happened) of the past. Our guesses – even those made with apposite triangulations of class and gender – about her characters invariably turn out to be wrong. And yet for all Harris’s skills of characterisation and her fine ear for dialogue, buried within her books is an even bigger hook. Because when you read one, you’re never entirely sure what kind of novel it is going to turn into.

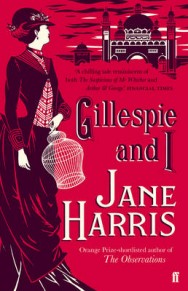

Take Gillespie and I, her second novel. All three are good, but this one – set in late 1880s Glasgow with a coda in 1930s London – is my favourite (it’s hers too – mainly, she says, because she felt she pulled off the challenge “of writing about a character far more intelligent than I am”).

To me, Gillespie and I is a “buttonhole novel” – one you really just want to shake people by the lapels and tell them to read, rather than explain why. In fact, explaining exactly who its central character is and precisely what she does would spoil your enjoyment of the book just as much as someone in the next seat at the cinema nudging you in the ribs and warning you to watch out for Michael Myers would ruin watching Halloween.

Its plotting is extraordinary. Most writers would deal with the deceptions at its heart by splitting the story into two and telling it from two different characters’ points of view. Instead, Harris stirs a pile of contradictions – carefully rationed at first, heaps at the end – into a single narrative. Lord knows how she manages to pull it off – along with a credible time shift and a plot turned almost inside out – but she does. It is one of the finest examples of Scottish historical fiction written this century, and why it didn’t even make the shortlists of a single prize for literary fiction baffles me.

Sugar Money, the novel Harris will be talking about at the Edinburgh book festival, is hugely different from both these novels: Lucien, her first male narrator, is a teenage slave with an adored elder brother, and the plot is based on a true story that happened on the island of Grenada in 1765. Fidelity to the historical record is a necessary constraint on the plot, in which Lucien accompanies his elder brother on a mission to assemble and transport a shipload of stolen slaves from Grenada to Martinique. Harris’s use of language, however, remains mercurial, with Lucien’s wild mixture of English, French and Creole consistently convincing.

Harris is white; her lead characters here are black, and many white writers might have been deterred by that from starting the story in the first place. “Of course I’m aware of my white privilege,” she says, “and I did ask various friends, writers of colour, if I was crazy to tackle such a subject. They told me that yes, I probably was crazy – but as long as I did it well enough, it wouldn’t matter. So I knew I’d have to write a good book.”

She has. This is a book that fully realises, through the lively mind of an adventurous but essentially naive 13-year-old, the horrors of slavery largely by showing just what Lucien has learnt to take for granted. It trashes any notion that Scots were somehow uninvolved in slavery, and fully realises all the cruelty, horror and tragedy involved. Yet this is, at the same time, a story of fraternal love, escape and adventure: the spirit that hovers above it is that of Stevenson, whose The Beach at Falesa was, Harris says, her “touchstone book”.

Though it didn’t win, Sugar Money was shortlisted for the Walter Scott Prize for historical fiction earlier this summer, the only novel by a Scottish writer on it. Her next novel will, she says, be her first with a contemporary setting, so her reign as Scotland’s queen of historical fiction could be coming to an end. Before it does, don’t make my mistake. Read a Jane Harris novel. If you’ve already read one, read all three. Because you’re worth it.

Sugar Money by Jane Harris is published by Faber & Faber and priced £14.99.

Jane Harris will be at the Edinburgh International Book Festival on 23 August.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

The Inciting Incident

The Inciting Incident

‘A room can have disorder or stains in it. But this room does not, will not. All is in order, now. L …

David Robinson Reviews: Sugar Money by Jane Harris

David Robinson Reviews: Sugar Money by Jane Harris

‘What I love about Harris’s novels is the way that they take the uncertainties we all have about the …