‘I feel as if my skin were glass, as if you read my thoughts almost before I think them.’

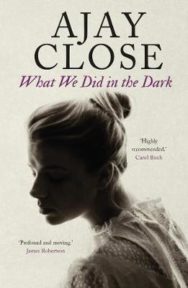

Catherine Carswell was an author, biographer and journalist of the early 20th century best-known for her controversial biography on Robert Burns. Before her writing career took off, she married Boer War veteran Herbert Jackson after a very quick courtship and their separation led to a landmark divorce case. Ajay Close has written a stunning novel, What We Did in the Dark, based around the events of this first marriage, and in this extract, we witness one of their first outings together.

Extract taken from What We Did in the Dark

By Ajay Close

Published by Sandstone Press

A school of arms!

You are amused by my surprise. Did I think you would belong to the sort of club that charges its members to sit in button-backed armchairs and read the newspapers? You had your fill of that in Liverpool. A nest of bullies and gossips, just like school. After a day at the easel, a physical contest, man to man, is just the thing for your aching muscles. They are all vigorous, good-natured fellows here. Anyone with a nasty streak would soon be drummed out.

The ladies’ sitting room overlooks the fencing hall. A smell of powdered rosin and sweat rises from the men below. Some are stretching, awaiting their turn with the foils. Others watch from benches. The wooden floor is marked with broad red stripes, allowing four separate contests to proceed simultaneously. The swordsmen dance up and down their allotted ground, left arms raised in a courtly flourish. Then, all at once, an interval of effortful grunting, the deft flurry of foils, and the hit, after which they separate. I would like to select a favourite and silently cheer him on, but how to choose when all look so alike in their white suits and padded breastplates, faceless behind their masks. It is a little like dreaming, watching so many ghostly antagonists fighting without motive or passion or the possibility of blood.

And yet my eye finds one of these grunting phantoms more sympathetic than the rest. I make him my champion. My ear picks out his stertorous breath, the thump of his soft-soled boots on the wooden floor. He and his opponent seem evenly matched, moving forward and back, neither gaining much ground. Attack, feint, lunge, parry, counter-attack, circle parry, disengage. No hits. For a long time it could go either way, but eventually my man’s movements grow sluggish, his foil less exact. Under the arms, his white jacket is wet. I watch the ebbing of his stamina, the effort to draw breath. The other’s eye is a fraction sharper, his hand a split-second faster. My champion knows it, and the prospect of defeat lends his swordplay a new fury. The thrilling pace is almost too quick for my unpractised eye to follow. It cannot last. My man begins to flail and stumble, lunging too violently, exposing himself to the counter-thrust.

A hit.

The men step back, lowering their foils. My champion rests a hand on his heaving chest and pulls off his mask to reveal a violent flush. The victor, too, unmasks. You! In my astonishment I laugh out loud. You look up, catching my eye.

In Glasgow there is an unbridgeable gulf between the burly coalmen shouldering their hundredweight sacks, the draymen hefting casks of ale, and virile intellects like Walter, pale from long hours indoors, eyes red-rimmed from straining to read fine print by lamplight. I never dreamed of meeting a man with an artist’s soul and the ruthless physicality of a soldier.

The restaurant is hardly bigger than a shop. The dim interior with its densely patterned wallpaper encourages conversation in lowered tones. To me the place feels delectably illicit. We take a table in the corner furthest from the window. Three prosperous-looking men sit over snifters of brandy. A pair of elderly widows despatch plates of breaded plaice. In the other shadowy corner, an exquisitely pretty woman is whispering with an older man too ugly to be her father. When you turn to see what I am looking at, your face shows such disapproval that I am moved to defend her. We can’t know she is a paid companion. Yes, he is old and fat and balding, but then so is the king and, if rumour is to be believed, he has broken his share of hearts.

‘Because he was Prince of Wales.’

‘Partly,’ I concede. ‘But don’t you think grossness can be attractive – at least, when it’s in tension with other, finer qualities?’

‘No, I don’t.’

‘Perhaps women are more susceptible to it.’

‘And perhaps you’re in a contrary mood, and you’d argue with me whatever I said.’

‘I would not!’

Your heavy-lidded eyes fix on mine. ‘Then those maidenly blushes hide a streak of depravity.’

There is a delicious edge to this teasing. I think your foil is safely blunted, but how can I be sure?

‘Never lie to me, Catherine. I shall always know.’

‘Is there no end to your talents – portraiture, swordsmanship and mind-reading too?’

You smile. ‘You have an unusually candid face. It shows every thought, like a pool rippled by the wind, never quite at rest.’

I am too pleased to know what to say.

‘Has no one ever told you?’

I shake my head.

‘Your eyes darken, or lighten. Your colour changes, flushing or paling—’ your hand stops just short of my cheek ‘—here. And here.’

You find me beautiful. It is as if I have been teetering across a rickety bridge, refusing to look down, my whole life. And now that you have handed me across to firm ground, I know I was never in danger of falling.

‘When a woman looks in the glass,’ I say, ‘that is, when I look, I refuse the face I find in that first instant, composing my features, almost without thinking, to achieve a more alluring reflection. I’ve had so many years of practice, it’s the work of a moment.’

‘So you’ve no idea how you appear to others?’

‘How can I know?’

‘I could paint you.’

And of course this is what I hoped you would say.

You ask what I did before studying at Glasgow University. I tell you about the Frankfurt Conservatory, how I went there in love with my own talents and, within a fortnight, knew myself quite ordinary. Even as I persevered, making the most of the opportunity I had been given, a spark in me had been snuffed out. Walter blew it into life again. He gave me an ear for the music of words. Not just Shakespeare and Donne, but the cadences of everyday conversation, the scope for playfulness and virtuosity over the breakfast table. His praise, quite unlooked for, resurrected my old brilliant self. Two blissful years as his student. If I had forgone Frankfurt, I might have had four and taken my degree, but the end would have come just the same. Brilliance might be charming in a girl, but it is no use to a grown woman, unless I marry well, like Mary, and can afford to host a salon. All my education has only rendered me less suited to living with a widowed mother who is good-hearted, but exasperatingly slow: a muddle-brained, trusting innocent. How can I leave her defenceless in the world? But how can I bear it, if I do not?

You listen without judging me, having your own forbidden thoughts about the futility of teaching. You have given up your position in Liverpool and plan to earn your living as a civilian engineer.

‘But you’ll still paint?’

You look down at the tablecloth. ‘It’s no great loss to the world.’

‘Even if that were true, it’d be a loss to you.’

It is so long before you reply, I wonder if you have taken offence.

‘I’m not sure it’s healthy to define oneself by a talent no one else believes in.’

‘I believe in it.’

The feeling in your eyes makes me think of a dog on a chain. Leaping up, to be yanked back down again.

‘Jackson! I thought it was you.’

A ruddy-faced man looms over our table. One of the brandy drinkers. There is a smear of custard in his half-handlebar moustache.

Your glance flickers, as if calling on all your reserves of patience. ‘Scotty,’ you say flatly.

‘What a turn-up, bumping into you down here.’

Scotty turns to me. You do not introduce us.

‘Just the other day, Gordon Duff was saying “I wonder what’s become of Jackson.” The club’s all at sixes and sevens, what with moving down the hill and all. No end of new blood about the place. That chap Muirhead they got in to fill your shoes seems very popular. Amusing fellow but solid, y’know. Not like whatsisname. Had to count the spoons every time he got up from the table. Dowdall says he’s a genius, but everything he painted looked sloppy to me. He’d do better swearing off the gin and getting fewer parlour maids in the family way. Still, rather them than Mrs D, if you catch my drift. What was his name… Julius, was it? Something of that sort. We miss those boxing classes of yours, y’know. Are you still fighting? In the ring, I mean.’ He prods your arm. ‘In the ring, eh, what? Never mind, old chap, just a joke. So, how are you making a living these days? I suppose studio work don’t put much jam on the table.’

He reminds me of a clockwork mouse I had as a child. It kept going, even when it met the skirting board, until the mechanism ran down.

One of his companions pays the bill. Scotty glances over his shoulder.

‘Well, I should really get back to, ah… Things to do, y’know. I’ll give the chaps your best.’

‘I’d rather you didn’t,’ you reply in the same flattened voice as before.

‘Oh, ah, as you wish.’ He sneaks another look at me. I make sure not to meet his eye. ‘Good luck, old chap.’ With a nod in my direction, he moves off to re-join his friends, who rise from the table and follow him out to the street.

‘I’m sorry about that,’ you say.

‘Who is he?’

Raising a hand, you get up to peer through the window. Satisfied, you sit down again. ‘He had the room across from mine at the University Club in Liverpool. For years I counted him as a friend.’

‘But not now, I gather.’

‘Many false friends have shown their true faces over the past two years.’

‘He seemed harmless enough.’

How cool you are suddenly. I curse this habit of commenting on things I do not understand.

The waiter passes our table bearing plates of empress pudding for the widows.

‘What’s the matter, Catherine?’

‘I hope you never despise me.’

You search my face. A blush rises up my throat and across my cheeks. I feel as if my skin were glass, as if you read my thoughts almost before I think them. Your gaze locks on mine, transmitting a beam of smoky light.

‘I hope so too,’ you say.

What We Did in the Dark by Ajay Close is published by Sandstone Press, priced £8.99.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

What We Did In The Dark

What We Did In The Dark

‘I feel as if my skin were glass, as if you read my thoughts almost before I think them.’