‘Our bones hold the nuclear tests in New Mexico, and so do wine cellars, trees and soil,’

Each year the Association for Scottish Literary Studies publishes their New Writing Scotland anthology. Here, we share two poems from the anthology, which includes work from from forty authors – some award-winning and internationally renowned, and some just beginning their careers.

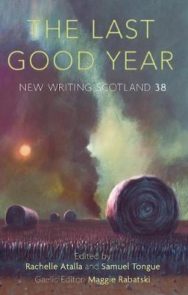

Poems taken from The Last Good Year: New Writing Scotland 38

Edited by Rachelle Atalla, Samuel Tongue and Maggie Rabatski

Published by the ASLS

GARDENER

Susan Mansfield

That’s how I see my father, looking back,

always stooped with a spade in his hand

slicing square sections from the rich, dark earth,

the rhythm of it, the heft of each cut,

leaving it furrowed and fresh, full of promise,

the mica gleam of it, ready for growing,

ready for roots. For the magic of growing

happens deep down where the land gives back

the lifeblood to the seedling, promising

fragile new things which need tended by hand,

and some will wither, such is the cut

and thrust, the mixed blessings of the earth.

My father claimed as his this patch of earth,

set aside plenty of ground for growing,

how he paced it out, how the sod was cut

without ceremony, how he bent his back

to building a home with his own hands,

with enough room in case the promise

in her eyes became more than a promise

and tending his seedlings in the dark earth

was just the beginning. How one small hand

changes all you know about growing,

the unflinching force of it, no looking back,

eyes on the wide horizon ready to cut

and run, but all so soon, the toughest cut

for man or gardener, seeing a promise

fulfilled by leaving you, then going back

to lay down next year’s crop in the mulched earth

and wait for the consolation of growing

while the furrows deepen on your gnarled hands.

I wasn’t even there to take his hand

at the last, which is the strangest cut,

holding the phone in the half-light, the growing

sense that the things we think are promises

are only good intentions, and the earth

receives everything but gives nothing back.

Now, the weeds grow thicker and in my hand

no spade to cut them. I made no promises,

feeling the turn of the earth at my back.

BLAST ZONE

Lotte Mitchell Reford

I want to write about meaningful things

but everything coming out is about fucking

or sometimes about churches. Often about how

I’m worried about drinking myself stupid

or to death. There is a story I’ve been wanting to tell

about the time I broke my leg and the morphine barely

worked,

how a man who loved me held my calf for an hour and felt

the split bones

pressing into his palms, and also a scene stuck bouncing

round my brain,

something I heard in an interview on NPR about nuclear

tests

in the ’50s and how they made young men bear witness to

the devastation

and gave them questionnaires afterwards to gauge its effect

on their mental health. Was it like a psychiatric intake form?

‘In the last week, on a scale of 1–7, how often have you

thought

about death’ – this one is always a 7 – or more like the

pain charts

they give you in an ambulance. Those ones have faces

to represent 0, 1–3, 4–6, 7–10. The only time I have pointed

at one of those little faces I had to ask what I was comparing

my current pain to. I’ve never felt anything worse than this

I said, my left tibia and fibula smashed into several pieces,

But someone must hurt more? Like, where are those men

now,

who after they watched the blast from a trench at a distance,

walked out in a line,

a search party, and combed the desert for what was left.

Those bombs are used now to measure everything

temporally. There is a before and an after; for bones, for

wine.

And in the middle of that hard dark line across time

were animals penned in the blast zone. The furthest out

lost limbs

and survived a while. Most of the animals were pigs

because pigs die like humans, and the guy I heard

on NPR, he said the worst part was how delicious

the whole desert smelled, a giant barbecue,

and that as they are dying like humans, pigs scream like

us too,

and yet, still, he thought of food. While we waited

for the ambulance Thom and I talked about pizza to

distract me,

pretending I’d be home in time for dinner.

In the hospital they pulled on my foot to reset the bones

above.

They told me not to worry because pain

is something we never really remember and anyway

I’d had all the morphine they could give me. I didn’t want

to point out

there are many kinds of pain, and some are hard to forget

some remain etched into you, your body and bones

or become a new kind of glass, Trinitite, superheated sand

which registers as radioactive. I didn’t want to tell them

that I had a hefty tolerance for opioids.

I never want to tell people who fix bodies

about the things I do to mine. Most of those men,

young as they were, must be dead now. Our bones hold

the nuclear tests in New Mexico, and so do wine cellars,

trees

and soil, but how do we hold those boys

with us too, how do we keep bearing witness,

how do we remember to remember?

The Last Good Year: New Writing Scotland 38, edited by Rachelle Atalla, Samuel Tongue and Maggie Rabatski is published by the ASLS, priced £9.95.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

The Last Good Year

The Last Good Year

‘Our bones hold the nuclear tests in New Mexico, and so do wine cellars, trees and soil,’

The Book According to… Craig Russell

The Book According to… Craig Russell

‘I think every writer explores the complexities, paradoxes and contradictions of their own cultural …