‘Once more I saw the Universe for what it is, infinite and pitiless; I could feel the sting of death in the barren frost, and yet was utterly happy.’

Martin Moran lived life in the mountains to the full. He climbed and guided in the Alps, Norway, the Himalayas, and in the mountains of Scotland, and his memoir describes his climbing experiences with a deep awe and respect.

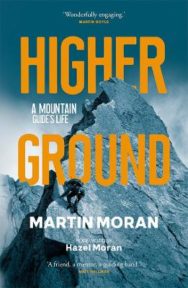

Extract taken from Higher Ground: A Mountain Guide’s Life

By Martin Moran

Published by Sandstone Press

‘Only a hill; but all of life to me

Up there between the sunset and the sea.’

Geoffrey Winthrop Young

I never especially wanted to be a mountain guide, but it was the hills that opened my soul to the wonders of existence. By the age of eight they had become a major part of my dreams and imaginings. I was born into an aspirational household that was making the post-war transition from working to middle-class status. Neither of my parents had the least inkling towards outdoor adventure. My mother was a dreamer, but was tied by the conventions of a housewife’s life. My father was provider and disciplinarian with scant time to spare from his career as financial accountant to a company in Wallsend on North Tyneside. Like so many of their generation both Mum and Dad sacrificed personal indulgence to give my brother and me the best possible starts in life, but their greatest contribution to my cause was unwitting.

Both parents had distaste for the conventional seaside holiday of the 1960s, and instead we were taken on touring trips in the Lake District and Scottish Highlands. My eyes were first opened to the hills through the back windows of a Vauxhall Victor. On Kirkstone Pass I saw grim crags rearing up into the mists on Red Screes. In Glen Lyon I marvelled at pencilled torrents which plunged from hidden heights. I urgently needed to find out what was where, to define and contain the world, and so became obsessed with maps. I accumulated a collection of Ordnance Survey One Inch sheets and became a devotee of Wainwright’s guidebooks. The strange Gaelic names of the Highlands – Sgurr nan Clach Geala, An Teallach, Bidean nam Bian – evoked a mix of fear and enticement.

Soon I was scampering up hillocks and hummocks during Sunday picnics in the Cheviot Hills. Langlee Crags and Humbleton Hill briefly meant all the world to me, but by now I had found the mountain bookshelf in North Shields library and my horizon widened. On a family drive to Devon the billowing masses of summer cumulus became my own Himalaya, every cloud cap a new and unfathomable summit, and with excitement came fear. One night in bed my imagination passed from the hills to the whole of the Earth and up to the sky. The stars stretched into a yawning and terrible abyss. Suddenly I sensed the ultimate truth and in a spasm of panic rushed downstairs to the arms of my mother. I now knew that a search for the absolute was futile, but I was not deterred from the quest. From fell-walks and camps to rock faces and bivouacs, the hills gave me solace and inspiration through my teenage years. All else in life seemed dull by compare and I won revelations of a life beyond the plain.

*

By December 1978 I was married and living in Sheffield. So far the magic of Scottish winter mountaineering had eluded me. I was steeped in the works of Bill Murray and the legends of Tom Patey, Jimmy Marshall and Robin Smith. The sublime experiences described by Murray in Mountaineering in Scotland convinced me that it was in this genre that the true force lay. Yet my previous trips north had all ended in storm or retreat through want of courage.

Lacking a ready partner I resolved to make a weekend visit to the Cairngorms alone and absconded from a tedious accountancy audit in the early afternoon. We owned a seventeen-year-old Ford Anglia, inherited from my late grandfather. I dropped Joy, my wife, with her family in Durham and drove north through torrential rain, battling self-doubt and loneliness. The 350-mile journey seemed interminable but the rain petered out to be replaced by snow showers, which fired mesmerising volleys of white daggers across the headlight beams. On the climb from Glen Shee to the Cairnwell thick banks of powder snow defeated the car. I parked and bedded down on the back seat, my mood morose but still determined.

A snow-plough appeared at 7.00 am and, tucking in behind, I surmounted the pass in triumph. My perseverance had paid off. Remembering the joys of a summer crossing as a fifteen-year-old Scout I was drawn to the Cairn Toul-Braeriach massif. The hike up Glen Dee was a soulless trudge and the hills were shrouded behind the veils of falling snow, but I kept my head down and climbed Cairn Toul from Corrour bothy without a stop. On the summit the visibility was less than twenty-five metres, so I took a direct descent past Lochan Uaine and cramponned delicately down the frozen water-slide of its outflow stream. Just before darkness I found the squat stone-clad Garbh Choire bothy, and settled in for the sixteen-hour night. Tomorrow’s likely outcome would be another dull trudge back to the car and yet another disappointment, but at least I was secure and warm.

In such expectancy I overslept my alarm by an hour. The bothy door opened to a morning of absolute clarity. The mountains shone under a white blanket of fresh snow. I couldn’t get packed quick enough. The snow was dry and aerated making the 600m climb to Braeriach an exhausting struggle, but what recompense there was in the views of the snow-plastered corrie walls around me. On reaching the summit, my sight ranged westward across the upper Spey valley to the white rump of Ben Nevis, which sailed on the skyline sixty miles away.

Anxious to squeeze every moment of pleasure out of this precious day, I ploughed down to the Pools of Dee in the jaws of the Lairig Ghru, straight up the east side, and on to Ben Macdui. Already the sun was slipping from my grasp. I pounded over the summit and descended towards the Luibeg Burn. Midday’s glare faded to a pale pink alpenglow, which flushed the high tops for a magical half-hour until the heavens turned to indigo, leaving only the western horizons with a fringe of light. The immensity of the vision moved me close to tears. A blanket of freezing fog gathered in the glen as I jogged down the icy track. Once more I saw the Universe for what it is, infinite and pitiless; I could feel the sting of death in the barren frost, and yet was utterly happy. The paradox is inexplicable. Back at Linn of Dee the Ford Anglia’s engine fired first time and a wind of elation carried me home.

Higher Ground: A Mountain Guide’s Life by Martin Moran is published by Sandstone Press, priced £11.99.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

Joan Eardley: Land and Sea – Life in Catterline

Joan Eardley: Land and Sea – Life in Catterline

‘Many of her landscapes were painted less than thirty paces from her front door.’

Environmental Picture Books

Environmental Picture Books

‘We share the best of our inspiring and beautiful picture books which help encourage wee ones to gro …