‘Many of her landscapes were painted less than thirty paces from her front door.’

Joan Eardley’s art was greatly inspired by the places dear to her. The latest book to celebrate her work focusses on the landscapes of Catterline, where she lived until the end of her life. Here, Patrick Elliott pays tribute to the spirit behind her work.

Joan Eardley: Land & Sea – A Life in Catterline

By Patrick Elliott

Published by the National Galleries of Scotland

The artist Joan Eardley would have been 100 this year, but her life was cut short in 1963, at the age of forty-two. She liked the countryside, but not the wilderness. Sublime Highland peaks and picturesque lochs held no interest for her; she responded instead to downtrodden working environments, particularly places where tight-knit communities held on in the face of modernity. Her favourite haunts, where she made most of her work, were the narrow Victorian streets of Townhead in the centre of Glasgow and the fishing village of Catterline on Scotland’s east coast, just south of Aberdeen – the focus of this book.

Eardley first visited Catterline in 1951, when she toured the area by car. A thriving fishing village in Victorian times, it had been bypassed by the railway and was too small for the bigger fishing boats, so fell into steep decline in the twentieth century. The young left and many of the cottages were abandoned. But the village spoke directly to Eardley’s interest in human resilience; the old and dilapidated were always, she said, more interesting than the new. A friend bought the old custom’s watchhouse for £40 and Eardley stayed there regularly until 1954, when she found a cottage of her own: No.1 South Row. She rented it for £1 a year. It had no electricity, gas or running water, a bare earth floor, no ceiling and hardly any furniture. It suited her perfectly. She eventually bought the cottage in January 1963, unaware of the cancer that would take her life just a few months later.

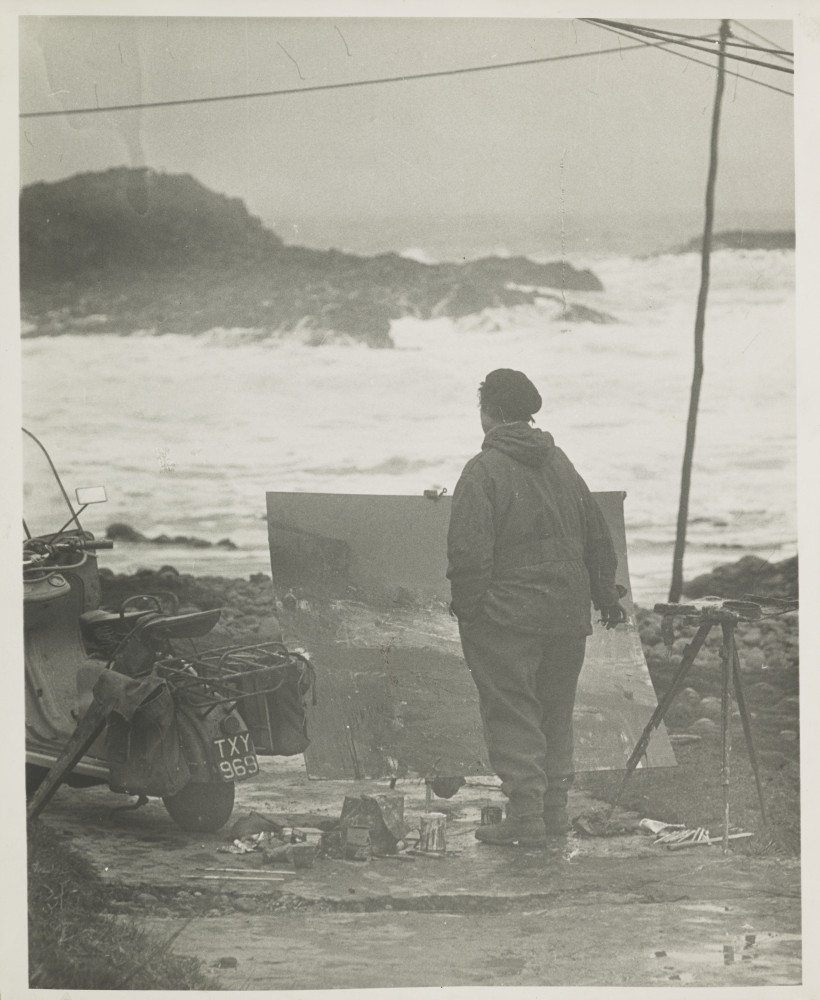

Eardley painting on the Makin Green, Catterline by Audrey Walker Credit line: © Audrey Walker.

Catterline provided her with all the subject matter she needed. The fields right behind the cottage offered an ever-changing source for her landscape paintings. The crops changed each year, from barley to corn, oats to grass – and the weather changed constantly too. Many of her landscapes were painted less than thirty paces from her front door. As she remarked in a letter: ‘It’s a lovely spot as no one comes near and I can always work away undisturbed … But every day and every week it looks a bit different – flowers come and go, and the colour grows – so it seems silly to shift about. I just leave my painting table out there, and my easel and palette.’[1]

Surprisingly, in the first five years she spent in the village, she seldom painted the sea. Rather than look out over the magnificent, crescent-shaped bay, she focussed her attention on the cottages. It was partly because she was used to painting tenement buildings in Glasgow, so she could adopt a similar formula in the village, and partly because she found the sea too difficult to paint at first. For a realist artist, whose training was based on analytical drawing, the churning, restless form of the raging sea must have seemed daunting. She approached it gradually; only in the last few years of her life did it become her central preoccupation. She painted the fields in the summer months and the raging sea in the winter. If she were in Glasgow and heard that gales were brewing in the North Sea, she would head over to Catterline on the train. She worked in all weathers, even using an anchor to moor her easel to the ground. You can still see the tight clamp marks at the edges of many of her sea paintings.

It is often remarked that in Glasgow Eardley painted the street children, and in Catterline she painted the fields and the sea, as if they were entirely different things. In fact, her Catterline paintings, like her Glasgow paintings, are rooted in the community. That was the main point of the book: to show that the village and the villagers were essential to her work. I was lucky to interview a number of people who grew up in Catterline and who remembered her; and chanced upon heaps of unpublished letters which tell of her daily routine – what she read, the music she listened to, village small-talk, long winter evenings sat by the fire. She painted the fields which had been sewn and harvested, the boats and nets which were used by the dwindling number of fishermen. Although she did not paint the people of Catterline, their working materials and their cottages and crops act as analogues for their lives. Stooks of corn and old nets can serve pictorial ends, but, in Eardley’s work, they also speak of resilience in the face of change.

Joan Eardley: Land & Sea – A Life in Catterline by Patrick Elliott is published by the National Galleries of Scotland, priced £24.99

Joan Eardley & Catterline is on display at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art (Modern One): Joan Eardley & Catterline | National Galleries of Scotland

[1] Joan Eardley Archive, National Galleries of Scotland Archive, A09/6

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

The End

The End

‘I think in general culture hasn’t fully reckoned with the climate crisis yet – both in real life as …