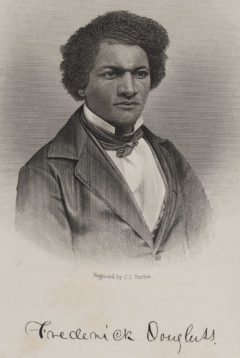

‘Scotland is at the heart of Frederick Douglass’ journey from slavery to freedom.’

Frederick Douglass is the most important nineteenth-century African American author, orator, anti-slavery activist, civil rights campaigner, statesman, and freedom-fighter in the world. Ahead of publication of the landmark book, If I Survive: Frederick Douglass and Family in the Walter O. Evans Collection, published later this year, the authors introduce Douglass’ pioneering life and trace how his fight for freedom over slavery led him to Scotland.

Frederick Douglass is the most important nineteenth-century African American author, orator, anti-slavery activist, civil rights campaigner, statesman, and freedom-fighter in the world. Born into southern slavery in Maryland, USA, in 1818, Frederick Douglass survived the traumas and tragedies of a life lived in “chatteldom” as he bore witness to his family being bought and sold on the auction block. In 1838, and at barely 20 years of age, he risked life and limb to make his escape from the “prison-house of bondage” and went on to become the most famous African American antislavery author and freedom-fighter in US history. As of April 2017, he was commemorated on the US quarter dollar, while his life remains the defining inspiration for former President Barack Obama as he repeatedly quotes Douglass’s belief: “There is no progress without struggle.”

Living a new life as a self-emancipated man in the nominally free North, Frederick Douglass was immediately appointed as an agent to the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery organization by radical white reformer, William Lloyd Garrison. Working tirelessly night and day, Douglass delivered thousands of speeches in which he powerfully and poignantly told “the story of the slave.” Starkly contrasting to white abolitionist supporters who relied on statistics and second-hand accounts to galvanize their listeners into action, Douglass became an instant sensation and a celebrated phenomenon due to his inarguable status as a living witness to slavery’s abuses and atrocities. An unparallaled orator, he was gifted with an unsurpassed eloquence: he relied on dramatic re-enactment, impersonation, invective, and song as he shared his first-hand memories and converted audiences in their thousands to the antislavery cause.

Scotland is at the heart of Frederick Douglass’ journey from slavery to freedom. When he made the transatlantic voyage in August 1845, he was on the run as a fugitive slave. His European sojourn in which he worked day and night to “tell the story of the slave” to audiences in Scotland, Ireland, England, and Wales was pragmatic as well as political. In April, 1845, only months before he embarked on the transatlantic steamship Cambria for Liverpool, he had published his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave. An instant bestseller, he put his life at risk by naming his white slave owners with the result that audiences knew, for the first time, that Frederick Douglass, the free man, had in fact started life in slavery as Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey. Here began the first role Scotland was to play in his life: he had made it to freedom in the North as Frederick Johnson but there were too many men of color of that name. Nathan Johnson, his friend and leader on the Underground Railroad, supplied him with the alternative that was to make him famous. As Douglass himself remembers, “Mr. Johnson had just been reading the ‘Lady of the Lake,’ and at once suggested that my name be ‘Douglass.’”

For Frederick Douglass as a formerly enslaved man, the association with the famous Scottish knight, Sir James Douglas, as memorialised by Sir Walter Scott in his romantic epic, Lady of the Lake, went beyond their shared surnames. Frederick Douglass saw in James Douglas, one of the chief commanders during the Wars of Scottish Independence, a kindred spirit who was equally committed to the overthrow of tyranny, despotism, and oppression. Writing from Perth, on January 27, 1846 to William Lloyd Garrison, Douglass jubilantly confides his new found sense of liberty by urging, “Frederick Douglass, the freeman, is a very different person from Frederick Bailey, the slave.” He declares, “I feel myself almost a new man – freedom has given me new life.” Yet more revealingly, he includes a direct address to one of the many white opponents he had known while he was still living as enslaved man in Maryland. “When I used to meet you, I hardly dared to lift my head and look up at you,” he concedes only to draw immediately on the living memory of Scott’s celebrated knight to proclaim that nothing could be more different now he is living in the land of James Douglas: “If I should meet you now, amid the free hills of old Scotland, where the ancient ‘black Douglas’ once met his foes, I presume I might summon sufficient fortitude to look you full in the face.” Celebrating his new found heroism that takes root in Scottish soil, Douglass issues an impassioned declaration of independence to his former oppressor: “were you to attempt to make a slave of me, it is possible you might find me almost as disagreeable a subject, as was the Douglas to whom I just referred.”

Over the decades, Frederick Douglass took repeated inspiration for his antislavery campaigning from the land of James Douglas which he celebrated as a centuries long battleground in the fight for freedom over slavery. Writing to his white abolitionist friend, Francis Jackson, from Dundee on January 29, 1846, Douglass exalts in “old Scotland” as a crucible of the struggle for human rights: “Scarcely a stream but what has been pouring into song, or a hill that is not associated with some fierce and bloodly conflict between liberty and slavery.” On remarking that he had seen “the Grampian mountains that divide east Scotland from the west,” he observes: “I was told that here the ancient crowned heads used to meet, contend and struggle in deadly conflict for supremacy.” As he freely admits, “I see in myself all those elements of character which were I to yield to their promptings might lead me to deeds as bloody.” While he was living in Scotland, Douglass lost faith in peacable antislavery protest and instead endorsed the “bloody deeds” of war. As US history confirms, he was to be proved right: slavery ended not as a result of abolitionist activism but due to the “deadly conflict” of a national Civil War.

Celeste-Marie Bernier is Professor of Black Studies and Personal Chair in English Literature at the University of Edinburgh. She is the author of African American Visual Arts; Characters of Blood: Black Heroism in the Transatlantic Imagination; Suffering and Sunset; World War I in the Art and Life of Horace Pippin; Stick to the Skin: African American and Black British Art (1965-2015).

Andrew Taylor is a Senior Lecturer in English Literature at the University of Edinburgh.

If I Survive: Frederick Douglass and Family in the Walter O. Evans Collection is published in September 2018 by Edinburgh University Press.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

Hari and His Electric Feet

Hari and His Electric Feet

Alexander McCall Smith: ‘Such is the power of dance to change our lives!’

The Sealwoman’s Gift: David Robinson Reviews

The Sealwoman’s Gift: David Robinson Reviews

‘Christian northerners being forced to survive among the infidels; the dismal realities of slavery a …