‘There’s an effortless joy in just standing still and letting the landscape – weird and familiar at the same time – seep into us.’

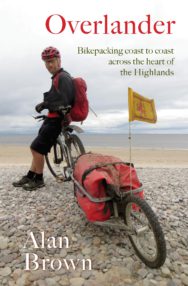

Alan Brown is some adventurer! In his new book, Overlander, he shares his story of one man and his bike, and a whole lot of stunning – if tricky to navigate – scenery.

Extract taken from Overlander

By Alan Brown

Published by Saraband

It’s only a short distance up the glen to the planned stop for the night – a bothy three kilometres away. The track up is loose but easy to ride, closely hemmed in by the trees at the start but opening out with a great view up the glen in the evening sunshine.

Bothies come in all shapes and sizes and all states of repair, and what little I’ve found online gives only a vague picture of the state of the building. When we reach the location, it is not that easy to spot as it’s set back some way from the track and nestled in among some mature broadleaved woods that run down from the steep crag above. The crag is cut in two by the gorge of the Allt Narrachan in a way that reminds me of Chinese silk painting, with the strong diagonal of the stream flicking from side to side before leaping off into a waterfall with trees perched either side on crazy ledges, the whole thing draped in half-formed or half-dispersed clouds. It is utterly bewitching.

There’s a long-forgotten field of rough, tussocky grass between the track and the bothy itself, and the kidney-swilling lurch across it, with the suspension squeaking and groaning in the perfectly still Highland evening, is a lovely end to the first day’s cycling. The thing with bothies is that you never quite know what you’re going to find. It may be that the bothy burnt down the day before or got trashed, but what you usually find is a rough shelter in perfect order, and sometimes there will be a couple of candles, some packet food or even a can of beer.

The outside aspect of the building is in harmony with the surroundings. It’s a traditional cruck-framed cottage, likely from the era of the iron foundry. The cruck-frame design allowed people with timber but no cement to build cottages where the roof beams sat straight on the ground, and the stone walls were built to fill the gaps in the timber structure rather than to bear any weight. The lack of pointing or rendering makes the whole construction look like something talented children have put together on a dry riverbed, and it has an organic feel to it. As I move to open the door, a mouse, disturbed in the long grass, shoots into the space between two boulders in the wall. Anyone squeamish about sharing with mice or spiders might be best advised to avoid bothies altogether, but they’d be missing out on one of the great pleasures of the Highlands.

Because bothies are open to any traveller to use, you never know who’s in residence. It’s polite to knock, so I do and wait for a reply that doesn’t come. It feels like we are completely alone here, apart from the mice. I duck under the projecting edge of the roof and step in and down onto the floor, which is what the French would call terre battue if it was beaten a bit more. It’s actually fine, dry earth. My first instinct on entering a bothy is to have a good sniff. This place smells clean and dry. It’s dim but there are a couple of neatly fitted windows made from corrugated PVC sheet. The interior décor is sparse but functional – three benches made from a pair of logs and a plank each, a couple of coffee tables of the same design, a rustic fireplace and a couple of branches that have been taken inside to dry. The inside surface of the walls has been neatly pointed with cement and the whole place is wind- and watertight. Some bothies have wooden floors, interior walls even, and furniture. This is the real thing, just a dry shelter open to any passing traveller.

***

Later that evening, Nathalie and I set out up the glen for a short stroll. It is simply beautiful. Not in the slap-in-the-face picture postcard way that Glencoe is, but there’s a verdant intimacy about the flat ground either side of the river, with the rugged foothills of Ben Starav to the north and the gentler hills to the south. The floor of the glen is carpeted in lush, green grass that comes up to our knees and in which each wave of the breeze is visible as it rolls down the glen and into the scrubby oaks and alders, their leaves flashing their silvery undersides in ripples.

There’s an effortless joy in just standing still and letting the landscape – weird and familiar at the same time – seep into us. Wandering slowly through the tussock grass, we come across the clear impression of a deer that’s been resting there, quite possibly until just a few minutes ago, out of sight and out of the wind. We could curl up together in the green saucer and see nothing but the clouds ambling across a blue sky now tinged with pink as the sun goes down.

Overlander – Bikepacking coast to coast across the heart of the Highland by Alan Brown is published by Saraband on 21 March 2019, £9.99

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

All Creatures Great and Small with Little Door Books

All Creatures Great and Small with Little Door Books

‘This is not just another Nessie tale, it’s a MONSTER story…’

Welcome to the Heady Heights

Welcome to the Heady Heights

‘Heady Hendricks looked like a million dollars … and he smelled like he had just bathed in Hai Karat …