‘All of a sudden, the age-old relationship between the subject and the artist’s representation of it has been turned upside down and inside out.’

In this latest book from National Galleries Scotland, coinciding with the exhibition at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art (Modern Two), Patrick Elliott shows us that collage as an art form has been with us for hundreds of years. Here he tells us why he put the book and exhibition together, and tells us a little about how the Cubists ‘invented’ the form.

Extract from Cut and Paste: 400 Years of Collage

By Patrick Elliott

Published by National Galleries Scotland

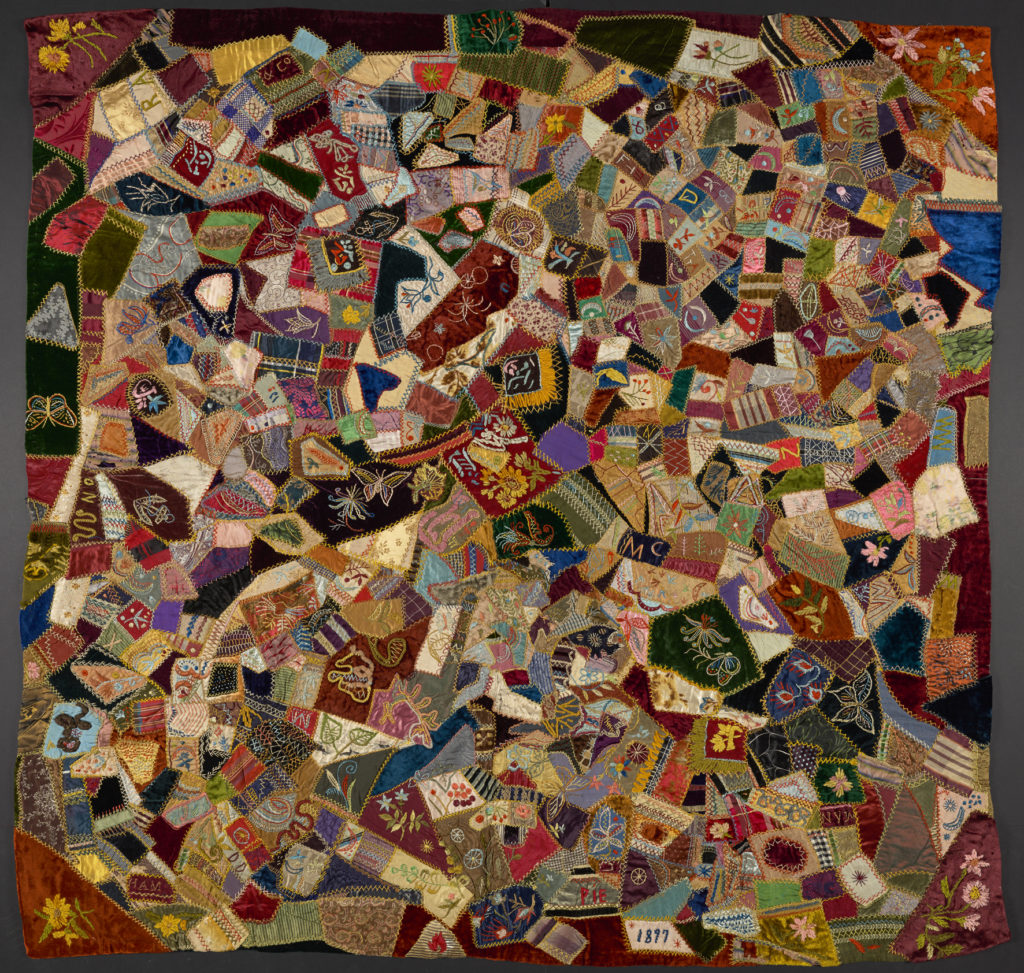

The idea of collage is so brilliant, so simple, so rich and imaginative in every way, that you might wonder why nobody had thought of it before. Well in fact they had, but historians of modern art have tended to ignore anything before 1912. Collage has a history stretching back hundreds of years, but at the time it was not called collage. That term, deriving from the French verb coller, meaning ‘to stick’, evolved as late as the 1920s. Before that it was called ‘scrap work’, ‘découpage’, ‘mosaick’ work and ‘adornment’. (In nineteenth-century dictionaries, the word ‘collage’ means bill posting and wallpaper hanging.) And the people who were cutting and pasting were not seen as artists. They were amateurs having fun, being creative and passing time. Many of the early collagists were women and children, and people with no formal training, such as tailors, writers and quilt-makers. Occasionally professionals used ‘cut-and-paste’ methods to save time and money, and early photographers used collage techniques such as photomontage and composite printing to get around the technical limitations of their art. Modern collage emerges from this amateur, craft activity.

In the 1910s collage – or papier collé as it was then known – was embraced by the Cubists, Futurists, Dada and Russian Constructivists as a way of attacking convention and mirroring the dynamic, modern machine age. In the 1920s collage became the favoured technique of the Surrealists. The French word ‘Surrealism’ means ‘beyond realism’ and that is where collage could take them. Collage allowed the Surrealists to fight academic traditions on the one hand, and on the other to create seamless, credible worlds suggestive of dreams and nightmares. The Pop Artists took to collage as a direct way of incorporating popular culture of magazines and posters into their work. In the 1960s and 1970s collage became a favourite tool of the Counter-Culture: it was cheap, quick and was, by its nature, disruptive. It was the technique of choice for the anti-Vietnam generation, and for Feminists, Punks and for anyone making photocopied Fanzines. Today, photoshop cut-and-paste techniques are used by millions of us, daily. Embracing the work of amateurs and professionals, men and women, children and photographers, film-makers and performance artists, collage is the most democratic, varied and inclusive of art forms.

We are in Paris and it is 1912: Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) and Georges Braque (1882–1963) have rebelled against the Renaissance ideal of trying to ‘copy’ nature and present a picture as if it were a fixed view seen through a window. Photography has taken over that job; a child with a Box Brownie can do better. Instead, they want to recreate the experience of looking at their subjects from a multitude of different angles and then build those different views into a single picture. It is an active approach, geared to the modern world of cars, planes, films and rapid change. They are wrestling with the paradox that the world is three-dimensional, and you can move about in it and it exists in time, while their pictures are flat and fixed. They are doing all sorts of innovative things: they introduce stencilled lettering which apes the flatness of newsprint; they add joke shadows to make it look as if nails have been driven into their canvases; they mix sand and grit into their paint. They want a new kind of realism, not illustration. Then in 1912 there is an epiphany. Instead of painting, say, a newspaper, or a wine label, or a chair, it occurs to them to glue a page of a real newspaper, or a real wine label or a facsimile reproduction of a chair seat, onto their pictures. All of a sudden, the age-old relationship between the subject and the artist’s representation of it has been turned upside down and inside out. Instead of trying to imitate something with paint or pencil, you stick it on the picture.

The ‘invention’ of collage by the Cubists is one of the most scrupulously analysed moments in the history of art. The story usually begins with Picasso’s Still Life with Chair Caning, which was made in May 1912 and includes a printed reproduction of a caned chair seat, stuck onto a Cubist still-life painting. It is often described as Picasso’s first collage. The baton then passes to Braque, who pasted pieces of paper bearing a printed wood-grain design onto a still-life drawing to make the first papier collé (‘stuck paper’), Fruit Dish and Glass, in the autumn of 1912. Picasso embarked upon a series of his own papiers collés in December 1912. Other Cubist artists, such as Juan Gris (1887–1927), followed their lead and added their own individual twists to the process: Gris stuck a mirror onto one painting and an engraving onto another but invited the buyer to swap it with a photograph of himself if he preferred. The Italian Futurists, the Russian Cubo-Futurists and Suprematists, and later the Dada artists, observed these developments with keen attention and took them in different directions. Braque and Picasso also made three-dimensional assemblages, which had a profound effect upon the development of twentieth-century sculpture. Even pure painters, particularly the Cubists, made paintings that looked like collages. Poets, writers and musicians also adopted the cut-up approach.

There is much literature on this watershed moment in art, largely focused on which one made which step, Picasso or Braque, and exactly when. In his celebrated essay ‘The Pasted Paper Revolution’ (1959), Clement Greenberg stated ‘Who invented collage – Braque or Picasso – and when is still not settled’. In his landmark study of Cubism, John Golding noted that Picasso ‘invented collage’ while Christine Poggi, in her detailed account of Cubist, Futurist and Dada collage, tells us that Picasso’s Still Life with Chair Caning ‘has acquired legendary status in the history of art as the first deliberately executed collage’. Another exhaustive account of Cubist collage and its aftermath, Brandon Taylor’s Collage: The Making of Modern Art (2004), begins with the chapter ‘Inventing Collage’.”

Cut and Paste: 400 Years of Collage by Patrick Elliott is published by National Galleries Scotland, priced £25.00