‘We wanted to experiment, try things out and see where they might lead. We still don’t know if what we do is art. That issue seems superfluous.’

Scotland’s visual artists were at the forefront of the cultural changes throughout the 20th century, and Bill Hare has captured their stories in his brilliant new book Scottish Artists in an Era of Radical Change. In this extract, Bill interviews The Boyle Family, the artist collective founded by Mark Boyle and Joan Hills in the 1950s who went on to become central to the counterculture scene in 1960s London.

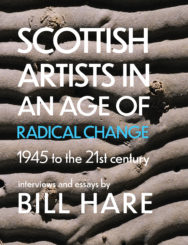

Extract taken from Scottish Artists in an Age of Radical Change: 1945 to the 21st Century

By Bill Hare

Published by Luath Press

The particular occasion for this interview is the acquisition and display of your Tidal Series at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art (currently on display in New Acquisitions at the SNGMA). Maybe we could begin by you giving an account of the making of this important work?

Sebastian Boyle: We all first went to Camber Sands in 1966, which is a very important trip in our work as that was when Mark and Joan made the first resin and fibreglass studies of the surface of the Earth. They had already moved on from making their assemblages to making the first Earth pieces using a grid system to transfer real material onto boards covered with resin. In the demolition sites in west London they were working in, they would find a board, cover it in resin and then transfer the real material from the site – whether that was bricks, stones, twigs, bottles, newspaper, dust, etc – to the appropriate place on the board.

But these transfer pieces were very heavy and had to be flat and Mark and Joan wanted to make larger pieces that presented the details and shape of the surface of the Earth, not just the detritus lying on top. They’d heard about resins and fibreglass and they wanted to experiment with these new materials. They needed somewhere where they would be relatively undisturbed and so a beach close to London seemed a good idea.

So we went there around Easter 1966 and the first Beach Studies were made. We then went back in 1969 when Mark and Joan wanted to make a series of works that included time as being an element in the work. Questions of time and change had been present in the 1960s projection works but the Earth Studies seemed fixed and permanent and they wanted to show this isn’t the case. So Tidal Series is a critical series for us. It introduces time into the Earth Studies and provides a link to the wider Boyle Family project. The series comprises 14 studies made on the same square of the beach after each tide, two tides a day, for a week, showing the constantly changing tide and ripple patterns created by the sand, the wind and the tide.

I would now like to turn to the broader aspect of Boyle Family as an artistic phenomenon. Unlike other artists, you have operated under a number of different names, such as Mark Boyle, Boyle and Hills, the Institute of Contemporary Archaeology, the Sensual Laboratory, through to Boyle Family. What were the reasons for all these name changes?

sb: Initially works were exhibited under Mark’s name, which was partly because when Mark and Joan started out, they didn’t expect to be making a living as artists. They and all their artist friends were sure they would always have to have second jobs to get by. When they started to exhibit in the early ’60s, most art dealers thought it was easier to sell work by a single male artist and, for Mark and Joan, the possibility they could actually make a living out of making art seemed so amazing that it was a battle which they felt they didn’t need to fight. All their friends knew that Mark and Joan were working together as a team. Mark’s name was almost a nom de plume for the two of them. Later in the 1960s, they created the Institute of Contemporary Archaeology and the Sensual Laboratory almost as front organisations to interact with ‘officialdom’ in some way, whether that was to help get permission to work at a site or deal with the police, a film lab or a hire company. Companies didn’t like dealing with scruffy looking artists. So the Institute of Contemporary Archaeology sounded appropriately official for doing the Earth Studies, and Sensual Laboratory was their production company for the projection pieces and later for their interactions with the music business. Then, over time, we shed those cover names and it just came down to the four of us working together and to give a public face to that fact we adopted the name ‘Boyle Family’.

Can I now go back to the beginnings of what eventually would become Boyle Family? Although both of you were originally from Scotland – Joan, Edinburgh, and Mark, Glasgow – you met by chance, or fate, in Harrogate in 1957. Neither of you had much, if any, formal art training, yet you wanted to make art together. What was it that made you feel you could form a creative partnership?

Joan Hills: Passion. I think it was just a sum total of wanting to be together, and working together, and bashing ideas around in the same space for a number of years and this is what came out of it. From the very first meeting we knew that we would be creating something together. He was writing poetry, I was painting, and we were interested in music, jazz, theatre and performance.

sb: You thought you were going to do something creative together but you weren’t thinking that would be necessarily as visual artists. It was a whole spectrum of possibility. Over the next few years you experimented with different art forms and techniques, such as happenings, projections, film, photography and sculpture because you were not sure which techniques and abilities you might need.

jh: Exactly. We wanted to experiment, try things out and see where they might lead. We still don’t know if what we do is art. That issue seems superfluous.

Joan, you and Mark moved to London at the beginning of what would later be known as the ‘swinging ’60s’. What was it like for you trying to break into the London art scene then and how did you establish your credentials as radical and innovative artists so quickly?

jh: When you were in it, how did you know when it was starting to swing? You didn’t. You were just leading an everyday life and still interested in the things that you were interested in, like going to galleries, listening to plays on the radio. If anything like the Theatre of the Absurd plays came to the Royal Court, we would go and try to see them. We were extremely interested in Beckett and seeing everything that was possible. There weren’t hierarchies that you had to get through. The old ICA on Dover Street was a place that people went to and hung around in because they were interested in pictures or writing or communication. We went to some of the shows and talks and met a few people.

sb: It was a small scene – I remember that you and Mark would say that when you were putting on an event, slightly later, in 1963–4, that you would call up 20 or 30 contacts and friends who were interested in what you were doing and who would come and support you – and vice versa. Whether it was at Better Books bookshop, the ICA, Signals, or, what did you say, Gallery One or Gustav Metzger’s event with the acid at the South Bank?

jh: That’s right.

sb: You weren’t really looking to establish yourselves as radical and innovative artists, were you? You were just trying to make work?

jh: No, we were just trying to get on with our lives.

sb: I think 1963 was really quite a turning point. Somehow you got the show at Woodstock Gallery under Mark’s name. You also went up to Edinburgh to visit your parents, taking slides of the assemblages with you and went round to see Jim Haynes who had started his paperback bookshop. He had a gallery in the basement, didn’t he?

jh: He wanted very much to get the things down into the basement gallery but some of them were just too large to go down the staircase. It was his suggestion that I take the slides round to the Traverse Theatre, which was in a tenement on the Royal Mile and when I got there, they were preparing for their first production at the festival. That’s when I first met Ricky Demarco. They didn’t have a gallery but he was very enthusiastic about what they were going to be doing and thought it would be great to put on our show at the same time in a room upstairs. So that was the beginning of the Traverse Gallery.

sb: It was in doing the exhibition during the festival that you met the artist Ken Dewey who’d been asked by John Calder to put on a ‘happening’ as one of the events at the international drama conference at the McEwan Hall.

jh: Yes. It was a very conflicting period for drama because many people thought that British theatre and drama in London were pretty superb but we felt that more exciting things could happen. Ken Dewey brought that out in all of us.

sb: Calder had asked two American artists, Alan Kaprow and Ken Dewey, to come over and do events to mark the end of the conference. Dewey worked collaboratively, particularly with local artists, and he must have thought that you and Mark were good people to get involved with his ‘happening’ or event. The event they put on, In Memory of Big Ed, was really the first British performance art event that went out into the wider public consciousness. It caused a huge furore because it had involved a nude model being taken across the balcony and was on the front page of most of the national papers. Questions were asked in Parliament and the police prosecuted Calder and the model. It caused a major scandal, but one unexpected consequence was that you were then the artists who’d put on ‘that’ event in Edinburgh. It wasn’t planned but it gave you a bit of a name and meant you were able to put on more events in London and get more people to come and see them.

jh: It didn’t feel as rapid as that at the time, but I’m sure these things counted. That’s absolutely true.

During that period of great social and cultural upheaval in post-war Britain, you were regarded as a vital force within the British Counterculture movement. How did you see what you were doing in relation to all the other changes that were taking place at the time?

sb: I have the sense that Mark and Joan were beginning to find a kind of identity among a group of people at the ICA who were trying to do something different, whether in music, theatre, film or art. It was a group of people who believed in experimentation, aware that they were part of a new generation trying to do something alternative to abstract expressionism or Pop art. They wanted to be grounded in the real world and real experience. Joan had done a bit of work with her film colleagues, working for the Labour party of Harold Wilson.

jh: Inserts for the election of 1964. We never saw Pop art as our thing, we saw it as fantasy somehow.

sb: You felt, though, that it was an exciting time, with Kennedy as President and Wilson talking about the white heat of technological change – the world was changing and Britain was changing.

jh: There’s no doubt that we were aware things were developing in different directions. Society was just breaking down a bit, as far as new ideas were concerned. It was a stimulating time.

Your wide-ranging activities during the 1960s such as your initiatives in the area of happenings and light projections have had a profound impact on the development of both British art and popular musical entertainment. Looking back, are you surprised that this aspect of your work has been so influential?

jh: No, because in the days of going to dances and things in the 1950s and early ’60s, ballrooms had glitter balls, music, perhaps a colour wash on a wall and that was it. Suddenly, we were able to create something that came from another background altogether, slightly scientific. In our projection events we were setting up little scientific experiments, which we watched as they developed and then we’d start another one and that would go on top of the first, then we’d fade one out, start another and so on. When we went to the States with Hendrix and Soft Machine, we found the big New York and Californian light show teams were doing something very different. In some ways more commercial.

sb: You weren’t thinking of it as being popular entertainment but an art event. You did some experiments with the projections on your own terms at home, for us, and for friends, then you started doing it on a wider scale, developing projection events such as Son et Lumière for Earth, Air, Fire and Water in art spaces, before you were asked to do a projection event, at the first night of the London underground club, UFO. I think it is important to say that UFO wasn’t only a great club and it wasn’t just about the music. It was a great art club. It was a place where theatre and dance groups performed, poets came and read and avant-garde films were shown. It was a meeting place for all sorts of alternative artists from all over the world and, while it became famous for the music and the projections that Mark and Joan were doing, I think that it was also very important as a creative hub. Their projections became the main visual element of the club and the bands who played there wanted these kinds of visuals for their gigs. The psychedelic light show has been credited with being the beginning of the big rock gig stage show with amazing projections and special effects – and Mark and Joan were there at the beginning.

Throughout the 1960s, in your monumental ambition to include ‘everything’ in your work, you took a multimedia, collaborative approach involving theatre, film, sound, music, archaeology and scientific research. Yet, by the beginning of the next decade you were cutting back on this highly varied approach and focusing mainly on what was to become the epic World Series. What brought about this change in artistic strategy?

sb: It wasn’t so much a change in artistic strategy as a change of scale. Up until 1971, Mark and Joan hoped that it might be possible to put on quite large-scale multimedia performances using projections, film and sound and at the same time make progress with the World Series and other Earth Studies projects. Indeed, the idea was that these events could be put on at museums to coincide with our exhibitions and that it would be an interesting way of showing the range of our interests, combining exhibitions maybe with our concerts with Soft Machine and contemporary theatre or dancers such as Graziella Martinez.

So the exhibition that launched World Series at the ica in 1969 was billed as being by Mark Boyle, the Sensual Laboratory and the Institute of Contemporary Archaeology, bringing together the Earth Studies, projections, events, body works and sound pieces. And Soft Machine did a gig with Boyle Family projections during the show and during the following exhibitions at the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague and the Henie Onstad Kunstsenter near Oslo. The combination of the exhibitions and the concerts was great for us, the museums and I think for Soft Machine, whose members liked playing in venues that weren’t the usual rock venues and festivals. It would have been great to have kept it going. Unfortunately, we then had a bad experience in Berlin in 1971 at an alternative culture festival, where we were putting on an exhibition, Soft Machine gig and a performance piece Mark and Joan had been developing called Requiem for an Unknown Citizen. This was an event piece studying society at large using theatre, random films, sounds and projections. The festival turned out to be a bit of a fiasco and we hastily performed Requiem instead at the De Lantaren Theatre in Rotterdam. This experience, coupled with the problems of having a theatre group and the financial problems it posed, led to the realisation that it wasn’t going to be possible to have a large team without major funding. Mark and Joan were still interested in making multimedia, multi-sensual work but the team was limited to us as a family and the presentations were kept on a smaller scale within the exhibitions, showing film installations before video became widely available to artists. There was a shift to the Earth Studies and the World Series in particular but we have always thought that the projections, films, sound works and happenings are part of our continuing overall body of work.

Maybe we should now concentrate on the work with which Boyle Family is most identified, the World Series. Could you tell us something about the circumstances that brought this mammoth project into being?

sb: After making the first Earth Studies in Camber Sands and then working on sites in the area around our flat in Holland Park, Mark and Joan wanted to do a London Series but, as they couldn’t drive, this was approximately a two square mile area of west London, which we could all walk to. Then we had to leave that flat as it was being knocked down to clear space for Shepherd’s Bush roundabout and Mark and Joan realised they couldn’t start a new London Series each time we moved and that, rather than do a British or European Series, they could expand the Earth Studies project to be a survey of the whole of planet Earth. The Americans and Russians might have been racing to get man to the moon but we could undertake our own study of the Earth. For the World Series, it was decided that 1,000 sites should be selected by using the biggest map of the world that we could find, blindfolding people, and then asking them to throw or fire darts at this map. We would then go to these sites and study them.

You must have realised that 1,000 sites randomly scattered far and wide across ‘the surface of the Earth’ would never be completed in any of your lifetimes. Thus you would have to be selective as to what you could accomplish. On what basis is the selection of sites made?

sb: No, Mark and Joan really did think that they were going to be able to do it in their lifetimes! They wrote in the catalogue for the ICA show that it was a 25-year project and that they could do 40 sites a year. We realised pretty quickly that it wasn’t going to be possible, probably when we went to The Hague in 1970 to do the first site and realised how much work was going to be involved. I think we’ve undertaken and completed approximately 20 of the 1,000 sites. Each one is a bit like making a short film – it’s a major undertaking. Of course, all the other works we’ve done have in a sense been helping us fund and make the World Series project. Quite often, the selection of which site we will do ties in with an exhibition. For example, while we were having a show in Oslo we went and made works in Norway and we made the Sardinian one for the Venice Biennale in 1978.

Your aim is to replicate these various sites as accurately as possible with80 out ‘any hint of originality, style, superimposed design, wit or significance’. When you’re in the process of making a World Series piece, what are the factors that allow you all to feel that you have fulfilled this demanding aim of absolute exactitude and objectivity?

jh: We use larger and larger maps to ‘zoom’ in to a site. Eventually, we throw a metal right angle in the air and where that falls is the first corner of the piece. We extend that six feet and work on that, and there’s never any question of saying, ‘it would be better over here or over there’. You couldn’t improve on what you get in a random selection.

sb: We know that it’s not possible to be absolutely exact and objective but we’re trying to be as objective as we can. The main thing is to take ourselves out of the site selection process. We then try and figure out how we are going to do it, whether it’s going to be one of our resin Earth Studies, or a film or video work that we’re going to make, or if there is some other way of doing it. I am not sure we ever feel we have fulfilled the aim of absolute exactitude and objectivity. Mark and Joan made a list of possible studies we were going to make at each site. We try to complete as many things on this list as possible, which includes making the actual study of the six-foot square, studying examples of animal and plant life on the site, the weather and what we call ‘elemental studies’ of the major types of rock and earth in the area. We include studies of ourselves in the project because we have to acknowledge that we are not neutral observers – just by being there we are having an effect on the site, so we include ourselves as active agents. We’ve never managed to complete the whole list.

Boyle Family had a major retrospective exhibition at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in 2003. That must have given you the opportunity to see the body of your work as an organic unity. From your point of view, what holds such highly complex and varied work together under the name of Boyle Family?

sb: That was a very important exhibition for us as it gave the British art world a chance to see the range and variety of the work and how it works together. There are all sorts of ideas and concepts that underpin our work. One of the key questions for us is how to look at anything objectively, to see it for itself. Not to look at it to tell a story or fit an agenda or even to make an artwork but simply to see, bear witness, record and maybe begin to understand. Mark and Joan came up with a number of frameworks for how to do this. One is ‘contemporary archaeology’ that we would study the contemporary world as if one were an archaeologist looking at evidence of a past society. Another key to understanding our work is the idea you have to ‘isolate in order to examine’. The question is how are you going to choose what to examine? Are you going to impose your value system, your value judgements, on that process? And how did you come by those values? Our random selection techniques are a way of trying to open up that process. They are far from ideal but they help. It’s not just the surface of the Earth we’re interested in, but everything – human beings, plants, animals, societies, physical and chemical reactions, bodily fluids and so on. We use random selection techniques to try and take ourselves out of the equation, to help us choose and focus on just a minute selection of the infinite number of possible subjects for study.

As artists who, although London based have their roots in Scotland, and over a long career have frequently exhibited north of the border, do you think of yourselves in any way as Scottish artists?

jh: You bet. This sounds parochial but because we have a World Series, that interest takes us everywhere.

sb: We certainly think of ourselves as Scottish artists and if there’s one trait which we see holding Scottish artists together – and maybe all Scottish people – it’s a certain bloody-minded determination to actually just get on with things. Maybe we needed that bloody determination in order to keep on going for 50 years.

This interview was conducted by Bill Hare in 2014 for Scottish Art News, issue 21

Scottish Artists in an Age of Radical Change: 1945 to the 21st Century by Bill Hare is published by Luath Press, priced £30.00

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

Enigma

Enigma

‘Balme’s pinch saved countless Allied ships and lives, and brought about the end of numerous U-boats …

David Robinson Reviews: This Golden Fleece

David Robinson Reviews: This Golden Fleece

‘Since the Bronze Age, much of Britain’s wealth has come from sheep’s fleece.’