‘Some strange congress takes place when you look at a seal, some hint of recognition, reinforced by the sense that it appears to be mutual.’

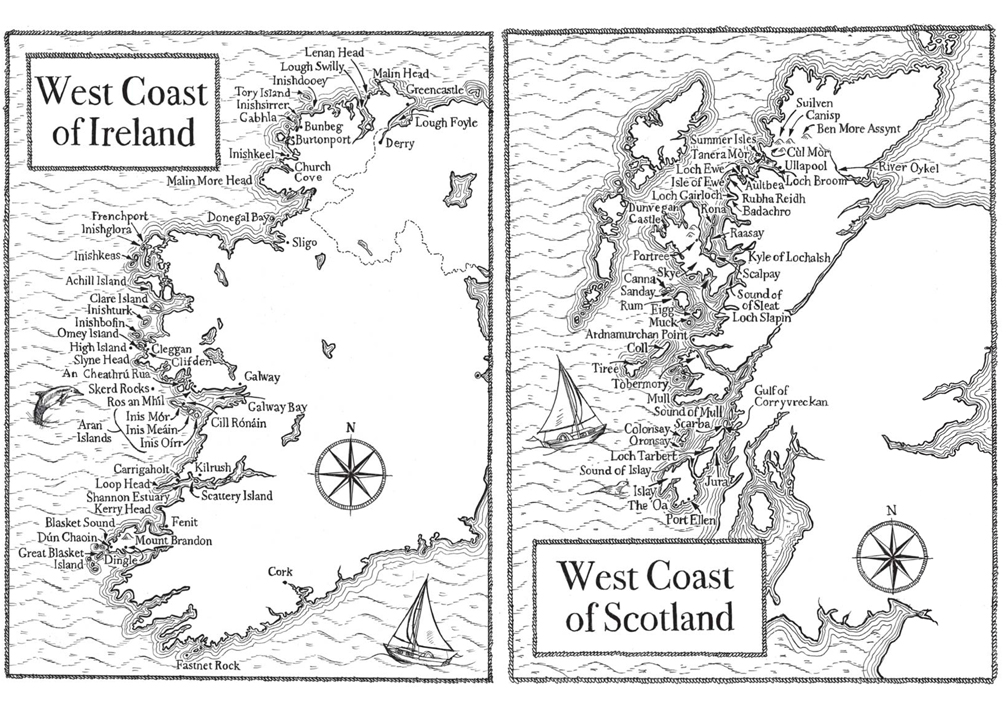

For Philip Marsden, the Summer Isles were a place of personal significance, a calling card to his imagination. In his latest book, The Summer Isles, he writes of his journey to the islands up the west coast of Ireland and Scotland. He explores how mythologies of places are created, and in this extract contemplates the importance of the Selkie while moored beside the island of Jura.

Extract taken from The Summer Isles

By Philip Marsden

Published by Granta

Map illustrations by Emily Faccini

Something made me turn. A head in the water, just a few yards from the boat’s quarter – two big eyes, whiskers, pale blotches on the neck. A grey seal. We looked at each other. It was hard not to read in its gaze a sense of surprise, an anthropomorphized reaction to this intrusive form in its bay: Who are you? What are you?

Seals were always selkies here, along the Atlantic coast. They led semi-human lives. They lived in their own world beneath the waves, one that mirrored that of people’s above. They were capable of human speech and human emotions, and they had underwater houses with doors and windows, the same as us. Once a year, they gathered at a place off the Donegal coast and elected from their number a leader a selkie king. Sometimes they could be heard singing of the seal city underwater, its coral gardens and its mother-of-pearl facades. To those who heard the song, it had a hypnotic effect: a delicate air, and words which spoke of a place ten thousand times more beau- tiful than the sky. The selkie world was a version of the otherworld.

Selkies could make near-seamless appearances on land. Female selkies would slip out of their sealskins and take on the form of women and sleep with men. Male selkies would also take on human form and father children. They might take those children back to the sea, or they might leave them on land. You could never be sure which were the selkie children; they might be very good at swimming, or very small, or ‘very sharp indeed at the learning . . . particularly at the Hebrew’. Then one day they’d just disappear. There were whole families in Ireland and Scotland who were known to have the seal blood in them, and the Scottish folklorist John Gregorson Campbell speaks of the Clann ’ic Codrum nan ron of North Uist, ‘the MacCodrums of the seals’, so named for their seal ancestry.

In the 1950s, David Thomson travelled in the west of Ireland and Scotland gathering selkie stories. In the tender account of his journeys, The People of the Sea, he tells of meeting a man of the road down in Kerry who was descended from seals. ‘The seals are a class of a fairy,’ explained the man. ‘They come out of the north of Ireland, from some place by the County Donegal.’ He then told Thomson about a boy who, collecting kelp one day, stabbed a seal. The boy watched as it turned into a red-headed man and ran away. Years later, when the boy was a man, he was fishing near Tory Island. When he went ashore, he saw that red-headed man, and the man said ‘thank you’ to the boy for what he’d done years earlier. He’d been freed from his seal-state by the stabbing.

Thomson not only recorded the habits of selkies and their place in the world, but also the relish with which their antics were told. The selkies could be malicious or a threat, but they were also characters, recalled like any old-time village eccentric. He remembered one man in north Mayo telling a selkie story: ‘Do you remember the seal we met outside chapel? You remember how it was walking like any dog.’ He said that someone hitched it up to a cart and put it in a hay shed and it spoilt the hay – no cow would touch it. It was Finoola Finney who drove the seal, he recalled, and she was a girl who was up for ‘any mad thing’ – and the man laughed so much that for some time he was unable to finish his piece.

Thomson heard another account of a man travelling to the annual fair in Belmullet. He was late and all the currachs had already left to cross the estuary. So he sat on a rock, feeling sad. A seal came up and addressed him by name. The seal said he was also going to the fair. So the man jumped on his back and they swam out to cross the tide. They were joined by other seals, all going to the fair. When they reached Belmullet quay, the man jumped off and waded ashore, then turned to thank the seal. But he was gone. Instead he saw ‘a fine gentleman’. ‘I am the seal,’ said the gentleman. The man took him to the pub and they drank rum together. Rum was the ‘seaman’s drink’.

The selkie stories were sustained on these coasts by the constant presence of seals. Some strange congress takes place when you look at a seal, some hint of recognition, reinforced by the sense that it appears to be mutual. In many places, seals were believed to be fallen angels, the ones who, expelled from heaven, fell into the sea. But it was less their angelic nature than their human habits that were recalled again and again. Seamus Heaney said of the seal belief that it represents ‘the old trope of human beings as creatures dwelling in a middle state between the worlds of the angels and the animals.’ Yet shape-shifting is less about affirming man’s separation from the beasts than the possibility that we remain a part of them. It implies a world in which the boundaries between things do not – or should not – exist. It is the same parallel country of fairies and angels, the spirit world, into which we might occasionally glimpse or even travel. We might be locked within our frames, within our own mortality, but a bit of us remains mobile. ‘Of bodies changed to other forms I tell,’ Ovid declares in the opening line of Metamorphoses, and goes on to make the case that our souls are essentially fluid, and ‘adopt / in their migrations ever-varying forms’. Introducing his own version of Metamorphoses, Ted Hughes reflects on the moment of transition, repeated in each of the poems: ‘Ovid locates and captures the peculiar frisson of that event, where the all-too-human victim stumbles into the mythic arena and is transformed.’ The tales might be salutary, cautionary or retributive, but they hold out the promise of transformation – and transformation answers to that perennial itch at the core of our condition: the dissatisfaction of being, and the promise of becoming.

The endurance of the selkie myth can also be explained as an example of the poetic faculty, where everything can be revealed by finding its parallel. It comes from that strange region of cognitive territory where the chaos around us is briefly ordered by analogy, and the analogy grows into story and the story evolves and mutates into myth, a species in itself, both true and untrue. Selkie belief is a measure of the abiding need for such ambiguity. We might think that belief means certainty, but it doesn’t – it works better as the accommodation of paradox. Seals can be people and people can be seals. That’s it.

In the Ordinalia, a series of medieval mystery plays written in the Cornish language, there is a discussion about the question that lies at the heart of Christianity, the same question that has vexed and divided Christians for 2,000 years: how can Christ be both mortal and divine? The Cornish play has an answer:

Look at the mermaid

half fish and half man.

God and man clearly

To that we give belief.

I woke in the night and lay listening. Every ten seconds came the sound of a wave being dumped on the beach. I went up on deck. The boat had drifted round to face north-west. Not a breath of wind. My masthead light was glittering on the water. Over the Paps a large moon was half-hidden in shreds of cloud, and I listened to the anchor chain below, mumbling as it dragged its links over the sand.

I became aware of another sound. It was coming from the skerries. I realized that it had been there on the edge of my sleep for some time. I focused the binoculars: in the moonlight, a jagged silhouette of rock, a black void, and, above the water, three softer shapes. The moonlight on their backs gave them a roundness, the sort of shape that only animate things can hold. Seals. The noise they were making was part foghorn and part wolf-howl – and for the briefest of moments, I thought I understood what it meant.

The Summer Isles by Philip Marsden is published by Granta, priced £20.00

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

The Stone of Destiny

The Stone of Destiny

‘Although the dream left her with a residual feeling of terror, she felt strangely hopeful.’