‘The water humbles us. That is a common refrain. It puts us in our place, and reminds us of who we are. And we are grateful for that.’

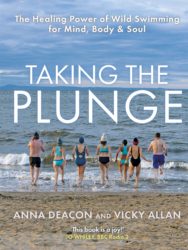

Wild swimming is becoming an increasingly popular pastime, and authors Anna Deacon and Vicky Allan extol the many reasons why this should be so in their gorgeous book, Taking the Plunge: The Healing Power of Wild Swimming for Mind, Body and Soul. Here they talk to fellow wild swimmers about the joy of being in nature.

Extract taken from Taking the Plunge: The Healing Power of Wild Swimming for Mind, Body and Soul

By Anna Deacon and Vicky Allan

Published by Black & White Publishing

THE INTIMACY OF NATURE

There’s something about being in water – the sea, a river, a lake, a pond – that takes being in nature to a whole different level. You are literally immersed in that wildness and it can feel as if you are more connected to the life that bobs, swims and plunges around you than to any other. That same water that runs over your skin runs over theirs too. The sea in which you float connects to waters on other sides of the planet. In it, you feel small, yet also in touch with a vastness beyond yourself. Swimming in the same water as other creatures feels more intimate than breathing the same air. In water, our relationship to nature changes. Away from our own built environments, we are more on a level with other wild creatures, in touch with some other aspect of ourselves.

We know that being in – and within – nature is good for us. The Japanese have been practising ‘forest bathing’ for decades. There’s even a word for the connection human beings seek out with other living things – ‘biophilia’, coined by the American biologist Edward Wilson in 1984.

Worcestershire-based NHS psychiatrist Charlotte Marriott has long been interested in how evidence-based lifestyle changes can make a difference to mental health. She notes that the evidence in favour of spending time outdoors, and in particular exercising outdoors, for physical and mental well-being, is ‘becoming hard to ignore’.

She says, ‘I started to become interested in the power of spending time in nature after noticing the beneficial effects on me and my family. How a long walk in the countryside can defuse an argument, a swim can invigorate and energise, and a stroll through the woods can calm and relax.’

Charlotte cites studies that show the physiological and psychological benefits of time spent in nature. ‘Spending time in a forest once a month,’ she says, ‘can increase scores for vigour, reduce scores for anger, depression and anxiety and reduce the risk of psychosocial stress-related diseases.’ Trees even release chemicals, phytoncides that make us feel better. ‘They have a direct effect on human immune function and stress hormones.’

The list of ways in which time outdoors in nature can help us is long. Charlotte says it has also been shown ‘to reduce the risk of type II diabetes, cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure, stress, anxiety and depression, and increase sleep duration, perhaps because exposure to green spaces reduces the level of stress hormones: cortisol in saliva and adrenaline and noradrenaline in urine’. And, here, in the UK, GPs in Shetland have piloted the social prescribing of rambling and birdwatching.

That sense of biophilia is there in our feelings about open waters. The sea, and other big bodies of water, are wild places. We can’t see beneath the surface and we can’t breathe, and so we feel like interlopers. Blinded, but for goggles, suffocated but for the gulps we take when we come up for air, we don’t know what’s down there, what monsters – or other more benign creatures – might lurk. More used to the sea, we might feel panicked by the darkness that greets us when we put our faces into a lake’s dense waters, more used to the clear waters of the sea. Yet, curiously, once in these wild waters, many swimmers feel like they belong. They find their wild selves, and they find themselves at home.

A DISSOLVING OF BOUNDARIES

People have always swum in the waters of this planet. Their watery adventures have been recorded in our art; in the paintings, for instance, in the 10,000-year-old ‘Cave of the Swimmers’, with their delightful procession of doggy paddlers. Swimmers are there in mosaics at Pompeii and Ancient Egyptian ceramics. For non-swimming reasons, we have settled next to our seas and waterways, travelled on them, fed ourselves from them. Some suggest we are evolved from aquatic mammals, and there is even talk of us having a ‘blue mind’.

Wallace Nicholls, who wrote a book with that title, in a popular a TEDx talk observed, ‘When we’re with the water, it washes our troubles away. When we’re standing at the sea, taking it in quietly it takes away our stress. It’s one of the reasons we love the ocean so much. It reduces our anxiety. It connects us to ourselves.’

Victoria Whitworth, in her wonderful memoir, Swimming With Seals, writes that in the water, ‘I know I am part of something much bigger than myself. I feel myself dissolving.’ She relates that feeling to that loss of boundaries described sometimes as oceanic feeling, an idea discussed in the 19th century in letters between Sigmund Freud and the French writer Romain Rolland.

Even looking at images of water relaxes us. Project Soothe, a study at Edinburgh University, has been finding that many of the images we find most relaxing and soothing are those involving water.

For many wild swimmers that sense of connection with nature is one of the biggest reasons they are there. ‘I was brought up on a farm in the country,’ says regular Edinburgh swimmer Jane, ‘and living in a city has always been a bit strange for me, so I’ve looked for ways of connecting myself to nature and the seasons. I grow veg here. Swimming in the sea feels similar because it’s another way of connecting.’

ELEMENTAL RHYTHMS

With its tides and swells, its changing currents, the sea is also a reminder that not everything conforms to the kind of timetable we have constructed our lives around. Being in a body of wild water also demands our attention in ways that so much of our contemporary lives don’t – it might sound glib, but you can’t check your phone out in a loch or worry overly about how Insta-friendly your look is. Wild swimming becomes something of a radical act, a deliberate rejection of digital distractions in favour of more elemental activity. Although online information and specific apps can help you stay safe, there is no doubt about the sea as a vast force beyond human control once you are in it. Appreciating that – on a visceral level – truly is a life-changer.

When we’re in water, no longer standing on two legs, wildlife seems to notice how different we are too. They regard us humans afresh, eye us in a different manner. Birds study us curiously, as if wondering what exactly we are. Wildlife guide, James McGurk, describes occasions when he has bobbed up close to creatures. ‘I’ve swum with a few animals that would otherwise be startled if you approached them on land, but just aren’t really bothered about you swimming in the sea.’

People, too, seem to have a different take on each other in the water – as if we’re all just part of the wildlife. Mary-Jayne is a London-based therapist and eco-psychology pioneer, who swims regularly in the women’s pond on Hampstead Heath, which she describes as ‘a diverse community of women, birds, water and more’.

‘I’m swimming,’ she says, ‘with moorhens, Canada geese, swans and other women. The Women’s Pond is the first in a line of ponds fed by a spring. There’s a pond for men too, as well as a mixed pond; the other ponds are reserved for wildlife. I don’t know anywhere else in the country where you can go and immerse yourself in a wild pond with a group of women; it’s a particularly unusual place. Women often come to be quiet, to immerse themselves in nature, so from a spiritual point of view it feels very special.’

When we submerge ourselves with marine life, we are reminded of our place in the community that is the ecosphere, and even in history. ‘Once,’ says Lil, an East Lothian artist who swims all over Scotland, ‘when I was getting out of the sea, I saw an otter emerging. I realised I’d been swimming in the same body of water as this beautiful creature. That was really special. We are human, but we humanise our world so much that we claim these environments and forget that they are all part of our planet, and long have been. To be a part of that alongside other creatures who are living there is intensely humbling.’

The water humbles us. That is a common refrain. It puts us in our place, and reminds us of who we are. And we are grateful for that.

Taking the Plunge: The Healing Power of Wild Swimming for Mind, Body and Soul by Anna Deacon and Vicky Allan is published by Black & White Publishing, priced £20.00

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

To the Lake by Kapka Kassabova

To the Lake by Kapka Kassabova

‘Some places are inscribed in our DNA yet take a long time to reveal their contours, just as some jo …

Blazing Paddles: A Scottish Coastal Odyssey

Blazing Paddles: A Scottish Coastal Odyssey

‘The Scottish coastline remains one of the most magical, unspoiled places in the world for relaxatio …