‘This image of the great dark industrial city blazing with a source of simple widespread pleasure – something childlike in the enjoyment, yet something fitting in the extravagance of the display – is one that appeals to me very much, and it’s perhaps the one that most nearly shows the soul of the place.’

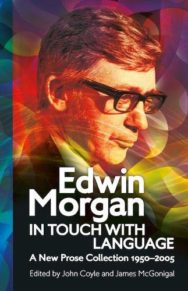

Edwin Morgan: In Touch With Language is an excellent new publication from ASLS collecting together a selection of Edwin Morgan’s best prose pieces. We’re thrilled to share the essay ‘Signs and Wonders’, celebrating his great city of Glasgow.

‘Signs and Wonders’ is taken from Edwin Morgan: In Touch With Language

Edited by John Coyle and James McGonigal

Published by the Association for Scottish Literary Studies

‘Signs and Wonders’

Arts and Entertainment / Out of London / Glasgow

Anyone who has lived for a while in Glasgow knows that it isn’t all rivets and razors, and that as far as entertainment and culture are concerned – on a year-round basis, and discounting such bonus events as the Edinburgh Festival – it’s possibly better off than any city outside London. Yet the image persists of a grim place and an uncouth folk: a fearsome porridge stirred up from vague recollections of No Mean City, Miracle in the Gorbals, and the tartan tammies, ricketies, and raucous cries of our periodical descent on Wembley. I wouldn’t want to deny that there’s some truth in the image. A certain forthrightness in Glasgow behaviour is not to be got over, and can cause trouble. A young man taken to court recently for assaulting a bus conductor in Argyle Street admitted the charge but is reported as having said:

I was sitting beside my wife and not bothering anyone. My feet were in the passageway and he asked me to get them in. When I wouldn’t he kicked them in. I waited till my wife was off the bus then I hit him. I thought he deserved it.

And certainly it wouldn’t be Glasgow without the highly animated scene in George Square at half past midnight on Saturday or Sunday morning, when a gay but wild mob hot from the dancing fights its way into the all-night buses bound for the huge Drumchapel housing estate. On one such occasion I heard a struggling matron, swept along in the torrent, cry in the anguished tones of Kelvinside, ‘It’s just disgraceful! Where are the police?’ This got a big laugh. Someone cried, ‘Are you kiddin’?’ I could see two policemen grinning in the background as they watched over this commonplace operation. It’s fun, life in Glasgow, so long as you don’t weaken!

But the bad days of the gangs of the 1920s and 30s, which cling like burrs to the image of Glasgow, are over, and Gorbals itself, though many slums still remain in it, is being steadily transformed, demolition by demolition, into the impressively spaced bastions and towers of Sir Basil Spence and Sir Robert Matthew – already a showpiece for visitors, and a first taste of the city’s renewal. Clusters of white ‘scrapers’ (as Glaswegians familiarly call them) are pushing up everywhere out of the grey (or more often black) Victorian sprawl. The redevelopment plan, involving twenty-nine areas of the city and the eventual construction of over two hundred tower blocks, with the highest flats in Europe among them (the thirty-one-storey Red Road massif, now taking shape), is bold, imaginative, and staggeringly ambitious. A Glasgow Hilton has been discussed; it would certainly not be out of place. Redevelopment has concentrated on housing, since slums were and are Glasgow’s major social problem. But we are to have an arts centre too, on the site of Buchanan Street goods station: a complex which will probably include a large concert hall (to replace the Scottish National Orchestra’s former home in the St Andrew’s Halls, gutted by fire), a civic theatre (for general and amateur use), a smaller theatre (for the Citizens’ Theatre company, whose Gorbals premises are scheduled for demolition), an exhibition gallery, and a restaurant.

These are plans, and plans are signs and wonders. But what sort of reality have we got to meet the plan? There seems no doubt that things are beginning to stir again culturally in Glasgow. New art galleries are springing up, and the active Glasgow Group of painters recently started a Glasgow Group Society (members get a 20% discount on works purchased) which testifies to growing public interest. This year has also seen a renewed awareness of Glasgow’s architecture. As more and more buildings are cleaned and ‘treated for starlings’, and as the smokeless zones begin to spread, the forgotten splendours of the Victorian city emerge again from the grime, and the New Glasgow Society was inaugurated in April (behind the specially floodlit columns of ‘Greek’ Thomson’s extraordinary church in St Vincent Street) to keep an eye on our Victoriana and at the same time to ‘encourage high standards of architecture and town planning in the Glasgow region.’ These two aims aren’t always compatible, and there have been battles between preservationists and developers, but at least buildings are being discussed and looked at again.

In music, there’s the growing success of the Scottish Opera company, marked this year by an ambitious and powerful performance of Boris Godunov, to add to the regular concerts and proms of the Scottish National Orchestra. And at two extremes musicwise, things seem to be swinging. Who would have thought of a Glyndebourne for Glasgow? Yet some people did, and if you join the Pollok House Arts Society you can have your piano recital and buffet suppers with Gainsborough and Goya for background, and stroll through the grounds of a handsome Adam mansion on the south side of the city. But if you prefer the Beatstalkers to John Ogdon, the open-air lunch-time concerts in George Square are ready to welcome you with scenes of mad enthusiasm. At one of these pop concerts in June, the fans forced the performers to flee and take refuge in the City Chambers, losing bits of their clothing on the way. Climbing statues and screaming may be more in the expected Glasgow image of hearty gregariousness than an andante at Pollok – yet both are there.

As for the theatre, one must always rejoice cautiously, but it does seem that the worst days of recession and closing down are over. There’s a new leaven at work here too. We have lost the Empire to the property developers, and the Royal is now headquarters of Scottish Television. The surviving theatres rely on a standard diet of revue, musical, pantomime, and light play, with occasional visits from Sadler’s Wells or the Royal Ballet. A pungent native humour, reductive and extravagant, is kept going by comedians like Rikki Fulton and Jack Milroy, Lex McLean, Clark and Murray, and a show will be advertised as ‘the biggest laugh since granny’s ceiling fell in’. In straight drama, there have been two interesting developments this year. One is the decision of the Citizens’ Theatre (which celebrated its twenty-first birthday in 1964) to start an experimental offshoot called the Close Theatre Club, in premises seating about one hundred and fifty, ‘up a close’ beside the parent company; this is expected to begin production in September. The other is the emergence of Glasgow University’s Arts Theatre Group, playing in the university theatre, as a spearhead of intelligently produced drama. This year they’ve done plays by O’Neill, Strindberg, Tennessee Williams, Genet, and Eliot, and they’ll be putting on a play by a Glasgow dramatist (Tom Wright’s Pygmies in the Coliseum) during the Commonwealth Arts Festival next month. The group have also run successful poetry readings and discussions. Glasgow, with two universities, a School of Art, and a College of Dramatic Art, has a large student population, and this is one of the areas in which amateur drama is thriving at the moment. I hope the new audience will not rest content with Pinter and Arden but produce its own native playwrights as well as actors and directors.

Traditionally, you think of Glasgow as being dancing mad, fitba’ daft, and fond of its pint. But the pattern is changing. There’s no doubt as much dancing as ever, and the sharply-dressed queues still shuffle into the brilliant portals of the Locarno and the other big ballrooms. They are lured by day as well as by night, with lunch-time disc sessions. But the many beat, jazz, and folk clubs offer the strong competition of a more intimate, informal, distinctive atmosphere. And then there’s the Maid of the Loch to take you on a ‘showboat cruise’ up Loch Lomond, with two bars if the jazz makes you dry: five hours for 8/6, not bad? Glasgow is still very much a football city, but ‘the gemme’ isn’t the all-absorbing obsession it once was when there were fewer alternatives. Geodesic domes over Hampden and Ibrox might help to re-people the terraces, but there’s still television and ten-pin bowling to pull in another direction. Neither standing shivering nor standing drinking seems quite so much in the inescapable order of things as it once did. New pubs, new restaurants, new hotels have multiplied in the last few years, and Glasgow has found itself liking Chinese, Indian, Italian, and Scandinavian food as a sudden extension of its naturally embracing and now very cosmopolitan soul. Another extension: it has lately been described as the ‘gamblingest city’ in Britain, and to a wandering onlooker this might well seem to be true: from the ubiquitous profusion of betting shops and bingo palaces to the very plush Casino Chevalier in Buchanan Street and the forthcoming Establishment cabaret-casino in Sauchiehall Street which is to be ‘the ritziest spot in Europe’ (ah those warm Glasgow superlatives!) with Danny Kaye and Diana Dors hot on the heels of Sammy Davis Jr and Shirley Bassey to help loosen our sporran clasps – not that we seem to need much encouragement. Maybe those exiled Post Office Savings Bank employees will require a Glasgow weighting to enable them to keep up with the highlife?

We’ve a lot yet to do in Glasgow: acres of sour crumbling tenements to raze; buildings above some of the finest shop fronts in the city centre which in their filth and neglect ought to shame any property owner; some fire-damaged shells which remain uncleared year after year; we need a good paperback bookshop, and an H.M.S.O. bookshop; we ought to be thinking seriously about extending the Underground; we want route-cards at our bus stops which don’t look as if they were painted by the office boy in an odd moment; we want, eventually, something pretty spectacular in the core area from the Central Station to the Clyde to balance all the peripheral skyscraping. But however Glasgow changes, it seems likely to remain a place of strong character. I’ve seen a lot of cities, from Paris and Moscow to Cairo and Beirut, and as a city-lover I find something to attract me in them all, but there’s a peculiar quality about Glasgow (it certainly isn’t charm) that fascinates and leaves its indelible mark. It’s partly the lingering violent mythology of the slums and the gangs and the sagas of the shipyards, partly what survives in things like the Orange Walk which with its banners and sashes and songs and trot has become folk art, a social ritual deprived of much of its religious bitterness. It has something to do with the paradox that a city which is in some ways very sophisticated (much more sophisticated than Edinburgh, for example – Edinburgh is a city which has never eaten the apple, but Glasgow has, and although it is deeper in sin it is readier for grace) is at heart rough, careless, vulnerable, and sentimental, its people using and expending freely everything a modern city has to offer, not out of civic-mindedness but for purposes of sheer human enjoyment. The Christmas lights are a case in point. Glasgow boasts that its Christmas decorations are ‘the best in the country’, and having seen the London ones last year I’m inclined to agree with the claim. Sauchiehall Street, Renfield Street, Buchanan Street, and Argyle Street – the main shopping routes – are canopied with a fantastic glitter which culminates in a riotous kinetic centrepiece in George Square. There are special buses in the evenings to ‘see the lights’; the shops do a roaring trade; people come in from far and near and the streets are blocked with cars. This image of the great dark industrial city blazing with a source of simple widespread pleasure – something childlike in the enjoyment, yet something fitting in the extravagance of the display – is one that appeals to me very much, and it’s perhaps the one that most nearly shows the soul of the place.

New Statesman, 13 August 1965.

‘Signs and Wonders’ is taken from Edwin Morgan: In Touch With Language is edited by John Coyle and James McGonigal and published by the Association for Scottish Literary Studies, priced £24.95

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

Lee Randall Reviews: We Are Attempting to Survive Our Time

Lee Randall Reviews: We Are Attempting to Survive Our Time

‘Compassion is Kennedy’s strong suit. Throughout this collection she traces psychological cracks to …

Beyond the Last Dragon: A Life of Edwin Morgan

Beyond the Last Dragon: A Life of Edwin Morgan

‘. . .they quizzed us, shared their cans of tea, felt our no muscles and laughed, surrounding us lik …