‘The old ways might be tiring and leave your hands calloused and scarred, but maybe they are the best after all.’

Patrick Laurie’s memoir on a year in the life of his Galloway farm invites David Robinson to think about the changing nature of our countryside.

Native: Life in a Vanishing Landscape

By Patrick Laurie

Published by Birlinn Ltd

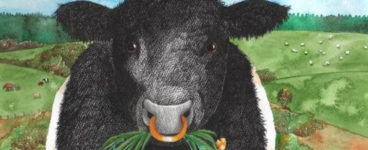

Patrick Laurie is always falling in love. The first time, the object of his affection is ‘blotchy, soft and perfectly gorgeous’. The second time, it’s her shape that attracts him – ‘a broad, tubby barrel with a wrinkle of fat around her neck’. Years later, he has a brief encounter that puts them both in the shade. ‘I smiled at the thickness which seemed to be unfolding in her legs and over her back. Deep veils of hair wobbled across her breast …’

We are, I should add, talking about ‘Riggit’ Galloways, and if you don’t know what they are, you almost certainly have never been smitten in a crowded auction mart by the urge to possess a local cow with a white stripe (‘riggit’) down its spine. Laurie, however, has, and in Native: Life in a Vanishing Landscape, he outlines why the breed has such a strong appeal to him.

Apart from their sheer bovine beauty, one reason is that ‘Riggits’, too, are natives. Go back to, say, 1800 and Riggit Galloways would already have been a century on the land Laurie farms near Dalbeattie, where his farmhouse is a century older still. Such continuity is precisely what’s vanishing from the landscape: older, smaller, cattle breeds are gradually being replaced by bigger, faster-fattening modern ones. In the process, not only did we lose better-tasting meat but a whole heap of biodiversity too.

In an interview accompanying its launch*, Laurie says he sometimes finds it difficult to explain what his book is about, and you can see why. There’s no immediately obvious focus. You might think it’s going to be about Galloway itself, but there’s precious little Gallovidian history in it, nor is it any kind of guide to what to see when you go there for a post-lockdown tour. There’s not too much about Laurie himself either or indeed anything about the upland farm conservation projects he has worked on that are mentioned on the inside back flap. Instead, Native starts out as lyrical trot through the farming calendar of the kind that you might well have read before. Stick with it, though, and it shakes loose from the format and becomes altogether more engaging.

At first, Laurie thought about calling it ‘the curlew book’. He had already written one about the black grouse, and curlews are far more important to him: they were the sound of his childhood, the music of his hills, and he has become obsessed with their survival. For curlews too are natives, even though ‘at the rate they’re going now they’ll be gone in a decade.’

But this isn’t a curlew book no more than it is about fancying gorgeous Riggit Galloway calves. Both feature heavily, both are becoming marginalised, both show the kind of countryside we are losing, and both can be used as a kind of shorthand for how it could be transformed. It’s this natural nexus that lies at the heart of the book and no, I don’t know how you’d work that into a punchier title either.

Curlews still come to Galloway, Laurie points out, but increasingly they’re just flying past on their way to lay their eggs in Finland or Russia. They’re hardly nesting here anymore, or at least not successfully: of the 111 attempts he’s watched in the last eight years, only 12 pairs survived long enough to produce chicks and only one chick lived long enough to fly.

For this, he blames three key F-factors: foxes, forests, and foot and mouth. Vast numbers of Galloways were slaughtered in the BSE crisis of the Nineties and faster-growing modern breeds were chosen to make up the numbers. Unlike Galloways, though, the new breeds won’t eat moorland grass or generally clear the way for the kind of habitat curlews seek out. Instead hybridised ryegrass continues its spread: a superfood with high nitrogen content, but one which could spell an end to the kind of plant and insect diversity curlews need.

This, in essence, is what Laurie is trying to reverse. It might sound like a fanciful ambition, and there are times, like when he opts to make hay rather than silage, when local farmers probably wonder what he’s playing at. Why does he harvest (and thresh) his field of oats by hand? Why does he forego an extra cutting of the grass that could provide him with two or three times more feed? The answer – an earlier cutting would devastate wildlife – would be lost on the students he meets at a local agriculture college. His fellow pupils, he says, ‘had never heard of curlews’.

The life he has chosen is a hard one, and he doesn’t shy away from making it harder still, constantly learning new skills such as how to mend his ancient David Brown tractor, sow a field of oats or slaughter a pig. But some of those hardships pay off: his bacon makes the shop-bought stuff ‘taste like wet salty paper by comparison’; the wild flowers return to the meadows; his herd of Riggit Galloways – he makes their meat sound so appetising that I’m determined to seek it out – slowly builds and he sells his first one. The old ways might be tiring and leave your hands calloused and scarred, but maybe they are the best after all.

The steady growth of his herd is a sad contrast to the childlessness he and his wife endure despite treatments for infertility. In the book’s penultimate chapter, Laurie describes the emotional toll this has taken on him. Sometimes, he says, working with his Galloways has fuelled his stoicism – they don’t question, the hills don’t question, so why should he? – yet at other times he feels ambushed by feelings of despair. He just doesn’t know, he says at the end of the book, whether he ever will have a child.

Well, I do. And he has. A little boy. And it’s a tribute to how much I enjoyed Native that I can’t tell you how glad I was to find that out.

* If you want to catch up with Patrick’s launch event, you can view it here.

If you would like to read an extract from Native: Life in a Vanishing Landscape, you can do so here.

Native: Life in a Vanishing Landscape by Patrick Laurie is published by Birlinn, price £14.99

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

The Seafarers: A Journey Among Birds

The Seafarers: A Journey Among Birds

‘Seabirds love islands, as I love islands: the further out of the way they are, the less disturbance …

All Hail Curly Tale!

All Hail Curly Tale!

‘After all, without our fabulous rural landscapes there would be no stories to tell! ‘