‘The really bizarre thing is to look at the other person and wonder who they are, what they’re doing there next to you, when it was that their facial features changed so much.’

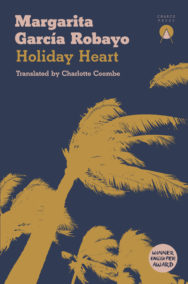

We’re big fans of Charco Press here at BooksfromScotland, so we’re delighted to give you a taster of their latest release, Holiday Heart by Margarita Garcia Robayo.

Extract taken from Holiday Heart

By Margarita Garcia Robayo

Published by Charco Press

That night, after they’re all showered and fed, Lucía logs onto Skype and calls Pablo so the kids can say hello. It’s hard to get full sentences out of the children, but they tell him, as best they can, about the seaweed, the brunch, their bodies buried in the sand. Then they start yawning and Lucía sends them off to their twin beds, in the room Cindy has decorated with old stu#ed toys she found in the apartment, left over from a previous life.

‘They’re shattered,’ she says. She is sitting at the table. The sound of the waves drifts in through the open balcony door. Pablo is wearing the same dressing gown he had on when she left. She wonders if he’s even showered. He’s in the study, with his back to the wall where a photo hangs of the four of them by the entrance to a funfair they went to a long time ago, in a farming town near New Haven. They’re all holding cotton candy. It was a happy day, or that’s what the photo implies. In reality it was probably hard work, full of tetchy discussions about whether the rides were appropriate for the children at that age, or whether they’d already had too much sugar. She suddenly has flashbacks of that day out: obese families devouring shiny glazed ham with their sticky hands; old people hauling other old people in their wheelchairs with their special passes for getting on the rides without queuing. And the ladies selling homemade cakes and syrups at the bakery stalls, while their kids scampered around excitedly, getting under everyone’s feet.

In the background she can hear the television: a Colombian soap opera, from the sound of it.

‘Lety’s here,’ says Pablo.

‘I know.’

‘You do?’

Silence.

They’ve been together for nineteen years. The strange thing is not the infidelities, thinks Lucía: she also committed some, although they were more discreet, more casual, nothing that’d put anybody’s heart at risk. The really bizarre thing is to look at the other person and wonder who they are, what they’re doing there next to you, when it was that their facial features changed so much. The accumulation of time makes strangers of us; nobody can say precisely when the seed is planted. The first symptom is disinterest, something miniscule that then becomes normal, and then both people stop wondering why they’re still there, oozing indifference towards one another, agreeing with what the other says as a formality: the time long gone when what they said seemed interesting. Or worth listening to.

Their relationship had been bad for a long time, but it had also been a long time since she stopped thinking she should do something about it. Sometimes she surprised herself in front of others, applauding the longevity of her relationship with Pablo. She would take his hand, look smugly at the others, and say ghastly things like, ‘Despite our differences, we’ve made it this far.’ What did she want, a medal?

She thinks about Franco. Nine or ten years ago.

Whenever Lucía spoke, Franco appeared to be giving her his undivided attention. But she could tell from the blank look on his face that the poor guy was just trying to work out the meaning of the words coming out of her mouth.

Franco was nothing to her, but she likes remembering him, especially now.

An intern who did her filing and brought her coffee. She’d offered to edit an internal publication for the scholarship program; it was a dull, time-consuming job for which she was paid a pittance, and which involved chasing up contributors to ensure they met their deadlines. She sometimes also moderated a virtual forum that the journal hosted for each issue; in general the themes were related to the Hispanic community in the United States, and the majority of the participants were resentful, aggressive immigrants who answered her opening questions with lines like ‘Show us your ass, sexy momma!’ The only help she had was Franco, which was as good as no help at all. She’d decided to get him out of the way, assigning him pointless tasks that would keep him away from her cubicle – where the guy usually sat in silence and watched her work – until the day he stopped behind her and started rubbing the back of her neck: ‘You’re stressed out,’ he said. How original, she thought. But instead of getting annoyed, she focused on the warm tips of his fingers pressing gently into the nape of her neck. She got up from her seat, turned around and was startled by what she saw in Franco’s eyes. Hunger. A young guy, with thick hair and very white teeth. Something was not right about it, but she didn’t care. She saw herself as if from outside her body, and barely recognised herself: a veil had been drawn over her, and now it was pulled back to reveal something too gruesome, too intimate. Scars, she thought, as she slipped her tongue into the intern’s mouth. A stump.

Rosa comes shuffling back wearing slippers.

Lucía is glad of the interruption, which breaks the excruciating silence and drags her away from her thoughts.

Rosa tells Pablo who they’ve got staying at the hotel.

‘David Rodríguez?’ he replies, pretending to be as excited as his daughter. ‘Wasn’t he injured?’

Rosa nods.

‘He’s on crutches.’

‘What a legend,’ says Pablo. ‘Do make sure you get a photo with him, darling.’

Rosa goes back to bed, smiling.

Lucía considers a few things to say and discounts them all as pointless.

She remembers Pablo crying, denying everything, even his own versions of events. Too scared to even look up. She sees him crouching in the bedroom, his dick hanging down limply like the clapper of a bell. Dark, wrinkled. Sordid.

Pablo leans back in his chair, briefly pulling a resigned smile. How long can they go on examining one another on-screen?

Sometimes, thinks Lucía, he’s such an open book, it’s just sad.

And sometimes he’s a padlocked trunk.

The dressing gown has a stain on it that looks like grease. His face is covered with sparse stubble, giving it the appearance of suede. His eyes stare into the screen in a way that reminds her of a photo of prisoners in Pakistan: pressed up against one another, gripping the bars of the cells with their nail-less fingers. She saw it in an exhibition, years ago.

Holiday Heart by Margarita Garcia Robayo is published by Charco Press, priced £9.99

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

The Strange Book of Jacob Boyce

The Strange Book of Jacob Boyce

‘”If I look at the picture long enough, if I focus my mind on the whole and on the detail, I’ll find …

Perfume Paradiso

Perfume Paradiso

‘A wine shop had one word above its window: Rossini. I admit, I was mildly excited about being in th …