‘Yes, it will be a story of our times, but it will draw on, and take hope from other times, and above all other fictions, too.’

Ali Smith’s Seasonal Quartet of books concludes with Summer. David Robinson tells us of his great admiration for the novel and its exploration of art, empathy and connection.

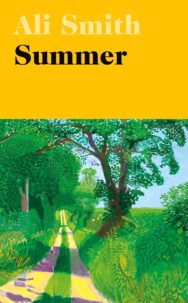

Summer

By Ali Smith

Published by Hamish Hamilton

Let’s start with the cover. As with Autumn, Winter and Spring, the one for Ali Smith’s Summer shows a David Hockney painting of a country lane. Each time, it’s the same lane, only now with the trees not golden brown, bare or beginning to bud but in full leaf, the hedgerows blooming with wild flowers and the heat hanging dreamily in the air.

In this particular non-summer, Hockney’s cover reminds us of the lazy, hazy, carefree days we’re missing. And as Smith concludes her seasonal quartet, in which each book has been written almost in real time but using story to explore our times, that kind of summer – the season we’re always looking ahead to, the one we yearly yearn for and feel we deserve, when nature will finally treat us well – seems to exist only in memory, imagination, history or art.

So here’s Grace, an actress playing Hermione in a touring production of The Winter’s Tale, remembering walking down a lane that could easily be the one Hockney painted. It’s 1989, and everything about that afternoon in high-summer Suffolk is perfect. Well, almost everything, because she’d just had a minor bust-up with the rest of the cast in rehearsal. They’d been talking about the play and why Leontes suddenly goes made with jealousy in it. Grace had said it was just one of those things:

‘A blight comes down on him, on his country, from nowhere. It’s irrational, It has no source. It just happens. Like things do. They suddenly change, and it’s to teach us that everything is fragile and that what happiness we think we’ve got and imagine will be forever ours can be taken away from us in the blink of an eye.’

Aha, you think, Brexit. Of course. And if you want to play that game of tying art down to politics with Smith’s quarter, you certainly can. Historians looking back on this decade will no doubt quote the opening of Autumn (‘It was the worst of times, it was the worst of times’) and its extended riff about how quickly divided the country had become after the 2016 referendum. They’ll probably also quote the opening of Summer (‘Everybody said: so? As in so what? As in shoulder shrug or what do you expect me to do about it?’) to illustrate the spread of apathy and the sheer weariness about today’s present.

Because back in Grace’s wintry present, in which she is a menopausal mum bringing up precocious teenagers Sacha and Robert in Brighton, Brexit is everywhere. She may have voted Leave, but her country is becoming graceless, intolerant, uncertain and tense because of it. Not only has her own family become divided but her former husband’s business has been ruined because of it and his girlfriend has literally become dumbstruck by it: she had been writing a book about political language, only to find it has become so debased that she can no longer even speak. To Grace’s son Robert, though, the sheer chutzpah of Johnson’s lies, racist tropes (letterboxes, watermelons etc) and callousness about the poor, his whole buffoonish schtick, is a source of impish delight. If you disagree, he tells his dad, you’re just a doomster and a gloomster, talking down Britain. In fairness, he’s only 13.

But even though Smith’s characters are mostly scathing about ‘the infantile Brexit obsession’ and positively vitriolic about Johnson himself, even though the clear-sighted activist Iris returns from Winter still fired up with revolutionary zeal against the ‘mighty Etonians’ who blundered unprepared into a pandemic, Summer is more than a diatribe on the state we’re in. It is also a dialogue – first with the other books in the quartet, then with history and art. Considering how Smith has had to not only weave the books together but do so against the tightest of deadlines (she only started writing in January) and the sudden interruption of Coronavirus, this is a spectacular achievement. As ever, Smith’s sends metaphors and puns spinning like a fairground waltzer, and we are reminded of just why Sebastian Barry hails her as ‘Scotland’s Nobel laureate-in-waiting’. Why Summer is not even on the Man Booker longlist is beyond me.

Perhaps I’m biased. I’ve known Smith for nearly all of her career as a published writer, and right from the start – from the ghost swooping into the hard ground in Hotel World – I have known that she can do things with fiction that few others can. Take this seasonal quartet. Who else would even have dared to attempt such a tight-deadlined tightrope walk? Gordon Burn’s 2008 ‘non-fiction novel’ Born Yesterday had a similarly time-limited focus on the immediate past, but was essentially a work of higher journalism rather than of the imagination. What Smith does is altogether different. Rather than string together a collage of recognisable political events, she wants to both stay close to, and slip the bonds of the factual present. Yes, it will be a story of our times, but it will draw on, and take hope from other times, and above all other fictions, too.

Take Daniel Gluck, the wonderful bookish centenarian composer we first met in Autumn. Maybe Smith always intended to bring him back for her coda, and certainly if she were mirroring the realities of 2020 she could have made even more of the lack of PPE in his care home or the vicissitudes of shielding. But no, she wants to bring him back for another purpose. So she slides us into his mind and we go right back to the summer of 1940, when, because his German father never secured British naturalisation, he is interned as an enemy alien. Locked down. His beloved sister, meanwhile, is busy working as a people smuggler, helping strangers flee from France and the Nazis to neutral Switzerland.

The conditions in Britain’s immigration detention centres have been targets for Smith’s fiction before. Here they are centre stage, every bit as important a symbol of the closing of the British mind as Brexit itself (which Charlotte, one of the returning characters from Winter, dismisses as ‘a fly on a corpse’). Justice for refugees, climate change – these are the causes for which Grace’s teenage daughter Sacha is campaigning, which require hearts and minds to be reopened.

To Smith, this is what art is for. Look, she says, as she follows Daniel Gluck into the internment camp on the Isle of Man in 1940: look at the work of those artists, at Kurt Schwitters and Fred Uhlman, at the work they and so many other interned artists made in their strange street-camp in Douglas. Look at how comparatively well, even in a climate of fear and populist ‘othering’, they were treated, how more open-hearted Britain was then than now. Look too at those other refugees and immigrants just before or just after that war, at Einstein, for example, or Lorenza Mazzetti, the Italian artist who is as much a guiding spirit of this book as Pauline Boty, Barbara Hepworth and Tacita Dean were of the preceding three.

Before I read Summer, I knew nothing about either Einstein’s time living in a Norfolk hut as a refugee from the Nazi Germany or about Mazzetti’s work as a film director, novelist, painter and puppeteer. Hers is a fascinating story. An artist who came to Britain from Italy as a ‘non-desirable alien’, she successfully demanded admission to the Slade, made a brilliant debut film (Together) featuring the young Eduardo Paolozzi, and founded the Free Cinema movement with Lindsay Anderson, Tony Richardson and Karel Reisz before returning to Italy a few years later.

Mazzetti and Einstein are linked by blood and tragedy – she was living in Italy with her aunt, who was married to Einstein’s cousin and when his family was massacred by the Nazis in the summer of 1944. She died this January, aged 92, and while I do not know whether Smith had already planned to include her in her book, her novel does acknowledge its debt to Andrew Robinson’s Einstein on the Run, which was only published last September. Even when dealing with the past, there’s a freshness to Smith’s work.

But let’s get back to Grace. When, in the novel’s present (a gloomy February), she revisits that Suffolk country lane in search of the bucolic bliss remembered from 1989, she finds instead that an internment camp run by private security firm SA4A has been built there. ‘It’s for people who don’t belong in this country’, a passerby tells her before throwing a plastic bag of dogshit on its barbed wire fence.

But Grace can still remember that hot Suffolk summer’s day over 30 years ago, when she was still an actress playing Hermione in The Winter’s Tale and was thinking about her role its strangely happy ending and whether or not this was plausible. She met a man and started explaining the play to him.

‘The Winter’s Tale,’ she said, ‘is all about summer, really. It’s like it says, don’t worry, another world is possible. When you’re stuck in the world at its worst, that’s important.’

Summer by Ali Smith is published by Hamish Hamilton, priced £16.99.

You can catch Sarah Wood’s film with Ali Smith at this year’s online Edinburgh International Book Festival. Book your free spot here.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

Uncanny Bodies

Uncanny Bodies

‘Imagine you put aside the pulse of fear at your throat and lean in, mirroring the stone’s tilt.’