‘This little bump offers a fabulous view right down the length of Glen Lyon and is well worth climbing, if only to understand why Tom Weir, and others, have described this as Scotland’s loveliest glen.’

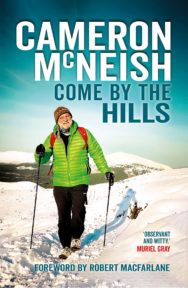

Cameron McNeish is one of Scotland’s most popular broadcasters on hillwalking. He follows up his popular memoir, There’s Always the Hills with his new book, Come by the Hills, which celebrates Scotland’s hills and his memories of walking them. In this extract, he walks to Glen Lyon in the Highlands and appreciates its majesty and mystery.

Extract taken from Come by the Hills

By Cameron McNeish

Published Sandstone Press

The Longest, the Loveliest and the Loneliest

Sir Walter Scott first described Glen Lyon in the above terms, and my mentor Tom Weir was fond of using the same alliteration to describe this thirty-four-mile-long glen of Highland Perthshire. He often told me Glen Lyon was his favourite, and for a man who knew Scotland like few others that was a high recommendation.

It is indeed a magnificent place, from its heavily wooded lower glen near Fortingall, where the River Lyon crashes and tumbles through its deep, shadowed gorge, all the way to the bare upper slopes of the glen, a place of desolation and remote mountain grandeur despite the hydro works that have dammed the loch, created a stony tideline around the shores and laced the upper glen with power lines. Notwithstanding the hand of man, Glen Lyon is famed for something else. It is also Scotland’s most mysterious glen, a place of myth and legend and, according to some, home to the creator goddess of the ancient Celtic world.

Years ago, I met an old friend of mine here. Lawrence Main lives in Mid Wales and has a penchant for New Age thinking. Lawrence describes himself as a Druid and has a long-standing fascination with the earth-mysteries and legends of our wild places. He had come north to Glen Lyon to visit Fortingall, a place he believed may have been the birthplace of Pontius Pilate, the Roman judge of Christ. Two thousand years ago, the legend suggests that Emperor Caesar Augustus sent an emissary to Scotland, to Dun Geal, near modern Fortingall. The emissary’s wife gave birth to a baby, and they called him Pilate. He went on to become the fifth procurator of Judea and ordered the crucifixion of Christ.

Lawrence was also searching for the Praying Hands of Mary, a large split rock that stands in Gleinn Dà-Eigg, an offshoot of Glen Lyon close to Bridge of Balgie. He also believed that Glen Lyon was the home of the Celtic creator goddess, and was itself a sacred place. Although megalithic remains are found just outside the glen, in Fortingall and near Loch Tay, Glen Lyon is curiously devoid of megalithic monuments. As the home of the creator goddess the glen was sacred by nature and such special sites were normally left untouched by the ancient Celts.

Lawrence’s revelations aroused my own long-standing interest in such mysterious matters. Just as North American outdoors folk have learned much from the native North American tribes, so I believe we can learn much from our Celtic ancestors, particularly about living in harmony with the land. Lawrence’s various speculations reminded me of a story I had been told some forty years ago by an old pal of mine, the late Harry McShane, a former warden of Crianlarich Youth Hostel and an erstwhile hillwalking buddy.

Harry told me a story about small stone figures that were apparently taken to a lonely spot near the head of Glen Lyon every spring, and removed again every autumn. He couldn’t verify the story and had no idea who moved the stones, but the tale has lodged in the scree slopes of my memory and my conversations with Lawrence Main encouraged me to carry out further research. What I discovered surprised and astonished me. This is the story of a pagan shrine dedicated to the Cailleach, in the tradition of the Celtic mother goddess, who once blessed the cattle and their pastures and ensured good weather.

The Cailleach, often translated as the ‘old woman’ or in this case the ‘divine goddess’, is a potent force in Celtic mythology, commonly associated with wild nature and landscape. The Celtic creator goddess is encountered throughout the length and breadth of Scotland, an entity taking many forms and represented in a variety of different shapes. Believers would see her essential nature in the harmony and balance of the natural order, the ebb and flow of growth and decay, of life and death itself.

Nearby, in Rannoch, legend names her as the Cailleach Bheur, the blue hag. According to A. D. Cunningham’s excellent book Tales of Rannoch this old witch was once a familiar sight on Schiehallion: ‘Her face was blue with cold, her hair white with frost and the plaid that wrapped her bony shoulders was grey as the winter fields.’

Other ancient forces have been at work in Glen Lyon. Years ago, just before I climbed the Corbett of Cam Chreag, high above the glen, I visited the little church at Innerwick. There’s a car park with interpretative signs beside the start of the right-of-way that runs over the hills to Rannoch and the little church is well worth a visit, just to see the ancient bell of St Adamnan.

St Adamnan, also called Adomnan or Eonan, was Irish-born and is famed for his biography of St Columba, whom he studied and worked under at Iona. Adamnan lived mostly in the seventh century and died around AD 704. His bell has been dated to AD 800 and apparently lay in the churchyard of St Brandon’s Chapel in Glen Lyon for centuries before being rescued. St Adamnan travelled here from Iona, setting up Christian cells on ancient pagan sites of worship. Another of his churches lies on the shores of Loch Insh, by Kincraig in Badenoch and, curiously, that church also has a bell that apparently belonged to the well-travelled saint. At Loch Insh, according to the legend, St Adamnan used to ring the bell to summon the Swan Children of Lir, a brother and sister who were half child, half swan, to worship. Today, Loch Insh, and its adjoining meadows, is Scotland’s principal wintering place for whooper swans. Coincidence?

I recalled these old stories as I climbed towards Cam Chreag, a 2,828-foot/862-metre Corbett that neighbours the Munro of Meall Buidhe above Loch an Daimh. I wanted some photographs of the loch and the wild land beyond it and remembered Cam Chreag as a pretty good viewpoint. I was also aware that the recommended route given in the guidebooks was less than satisfactory and a better route was possible by following the hill’s south-east ridge, returning to the start via its lowly neighbour of Meall nam Maigheach, a pleasant horseshoe-shaped route of about nine miles round the glen of the Allt a’ Choire Uidhre.

This glen has a bulldozed track running up its length to a corrugated iron hut just below Cam Chreag’s eastern face – the guidebook route – but the first bonus of my horseshoe route became apparent as I topped out on Ben Meggernie, at the end of Cam Chreag’s east ridge. This little bump offers a fabulous view right down the length of Glen Lyon and is well worth climbing, if only to understand why Tom Weir, and others, have described this as Scotland’s loveliest glen. On one side the peaks of the Ben Lawers range rise high into the sky, the pointed culmination of long, steep ridges. On the other, the blunter Carn Mairg hills rise on equally steep-sided flanks. The glen itself is wooded with the River Lyon flowing through green meadows. Rob Roy’s mother was born here, and before that the ancient Kings of Scotland came here to hunt deer.

Lovely as Glen Lyon is, I was more impressed with the views from Cam Chreag itself. To the west, the big Munros stood clear: Stuchd an Lochain and Meall Buidhe, one on either side of Loch an Daimh, and the wild country beyond to the hills of Mamlorn and Orchy. To the north-west, across the Rannoch Moor, Ben Nevis was clearly visible, rising above the hills of the Mamore Deer Forest and the enormous bowl of peat hag and heather, lochs and lochans that make up the vastness of the Rannoch Moor. Only the West Highland railway line offers any sign of man’s hand until you reach the A82 Bridge of Orchy road and the A86, away beyond the narrow slit of Loch Treig.

Come by the Hills by Cameron McNeish is published Sandstone Press, priced £19.99.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

A Vulture Landscape

A Vulture Landscape

‘Wherever I looked I could see these amazing birds, I was in a vulture landscape and my life was nev …