‘As I held the letters written in Conan Doyle’s neat handwriting from Undershaw, his house in Surrey, and from hotels across Europe, I could feel the obsession he had had with the case.’

Shrabani Basu is an author and a journalist whose latest book tells the fascinating story of how Arthur Conan Doyle became a detective and champion for justice in the campaign to pardon George Edalji, accused of mutilating horses in the English village of Great Wyrley. It’s an eye-opening look at race and an unexpected friendship in the early days of the twentieth century, and the perils of being foreign in a country built on empire. Here, in this extract, Shrabani Basu tells us of why she pursued this story.

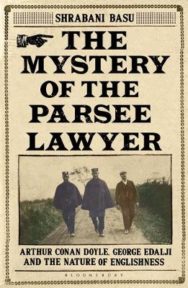

Extract from The Mystery of the Parsee Lawyer

By Shrabani Basu

Published by Bloomsbury

I had always been fascinated by the case of George Edalji, and Arthur Conan Doyle’s involvement in it. I had read about George briefly in books about Asians in Britain, but always wanted to know more. I wanted to know how Shapurji arrived in Britain, what made him convert to Christianity and how he became the first Asian vicar of a small village in the coal-mining area of Staffordshire. As they were the only mixed-race family in the area, I wanted to know about the racism the Edaljis suffered and how it had all impacted on George’s trial. Conan Doyle had compared it to the Dreyfus affair, but unlike that famous case, captured in history and literature by Emile Zola’s letter titled ‘J’Accuse’, and the subject of books and films, few today have heard of the Edalji affair. The story of the Indian man targeted for his race and religion in England was soon buried and forgotten, just another casualty of Empire.

I often thought about the family at the vicarage even as I worked on another book set in Victorian Britain. 3 It was the true story of Queen Victoria and her Indian servant, Abdul Karim, who quickly became a firm favourite and caused a storm in the royal court. She gave him land and titles. He introduced her to curries and taught her Urdu. The lonely widowed queen lived the last years of her life in an Indian dream with the handsome turbaned youth by her side. It was more than the establishment could take. Victoria’s household and family closed ranks against Karim and conspired to defame him. Unable to destroy him while the Queen was alive, they swooped on him within hours of her funeral, and burnt all the letters that Victoria had written to him (often several in a single day). He was unceremoniously asked to return to India, and every attempt was made to erase him from history. Though their circumstances were completely different (Abdul worked in the royal palaces, and George lived in a mining village), and their personalities were a world apart, there was one parallel between George and Abdul. Both were victims of racism in a society that was ready to believe the worst of a foreigner.

At the time I was writing, Julian Barnes published Arthur & George , a fictional account of the Edalji story. It was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize and I felt there was no point in trying to write anything more on the subject. Yet, every time I watched a repeat of a Sherlock Holmes drama on television, I would think of George Edalji and Arthur Conan Doyle. There is nothing quite like the calling of an unsolved mystery, a dark crime set in the English countryside over a hundred years ago.

In 2015 a small article in The Times newspaper caught my attention. It said that a collection of letters written by Arthur Conan Doyle dealing with the George Edalji case were to be auctioned. These were letters written by Conan Doyle to Chief Constable G. A. Anson, head of the Staffordshire police. The correspondence had never been published. It was a sign. There was hope of new material. I called up Bonhams auctioneers to look at the letters and made my way to their offices in Kensington. As I held the letters written in Conan Doyle’s neat handwriting from Undershaw, his house in Surrey, and from hotels across Europe, I could feel the obsession he had had with the case. Here was Conan Doyle wearing the deerstalker of his fictional detective, trying to solve the only mystery that he ever investigated himself. It coincided with a period in his life when he was coping with grief and emotional turmoil. His wife, Louise, had passed away and he was going to marry the love of his life, Jean Leckie. There was guilt about having loved Jean for nine years while his wife was ill and dying. In a way, the case of George Edalji lifted Conan Doyle from his melancholy.

‘In 1906 my wife passed away after the long illness which she had borne with such exemplary patience,’ he wrote later. ‘… For some time after these days of darkness I was unable to settle to work, until the Edalji case came suddenly to turn my energies into an entirely unexpected channel.’

Conan Doyle threw himself into the investigation, travelling to Staffordshire to meet the Edaljis and revisit the scene of the crime. His correspondence with Anson was combative. The chief constable was scornful of the famous crime writer trying to do the work of the police. Conan Doyle was convinced that the police evidence had been shoddy and that Anson was a racist. Anson’s personal notes revealed his character. . . .

Within the boxes lay a story, not just of the trial of George Edalji and the investigation by Arthur Conan Doyle; it was a story that went back to when George was just a young schoolboy in Great Wyrley, targeted for being the son of an Indian. Page after page of hate-filled anonymous letters lay in the boxes, directed at the family in the vicarage.

*

The events of over a hundred years ago in Great Wyrley could have been taking place in the present. Miscarriages of justice in Britain have happened before – the Guildford Four, the Birmingham Six – to name a couple. Prejudice, doctored evidence and decisions made on circumstantial evidence have also occurred in the recent past. In 1998, the Macpherson Report into the murder of black teenager Stephen Lawrence revealed there was institutional racism in the police force. In 1903, George Edalji was virtually sentenced before he had even walked into the dock.

The Mystery of the Parsee Lawyer by Shrabani Basu is published by Bloomsbury, priced £20.00.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

The Book According To… Ewan Morrison

The Book According To… Ewan Morrison

‘The question ‘What life-story can we live by? ’lurks beneath How to Survive Everything, and probabl …

Kitchenly 434

Kitchenly 434

‘There it would resume its coo-cooing loop of song and I would feel a sense of outraged sacrilege.’