‘What is special about the Cuillin is that they are Britain’s only true mountains, comprised of narrow rock ridges and jagged peaks.’

CALUM SMITH had been walking and climbing in the Scottish hills for 50 years but hadn’t published anything about the mountains until, astonishingly, in 2020, within a few weeks of each other, Rymour Books brought out two consummate and highly acclaimed works: The Black Cuillin and The Goatfell Murder.

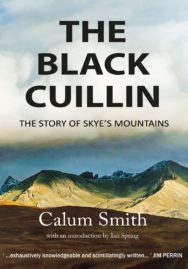

The Black Cuillin is a large book, in scope and substance, and it is probably the most detailed climbing history of any mountain area of the United Kingdom, if not beyond. Jim Perrin, a noted writer of mountaineering and travel histories, described it as ‘exhaustively knowledgeable and scintillatingly written. A monumentally good book’. Dennis Gray, a legendary climber from the golden age of British mountaineering in the mid-twentieth century, commended both books and called The Goatfell Murder ‘a work of outstanding research’, while another reviewer described it as ‘the best and by far the most comprehensive treatment of this infamous incident in Victorian Scotland. An amazing wealth of social history.’

For Rymour Books, Ian Spring commented: ‘these two books, unbelievably well written for a first-time author, were very important in the early development of our publishing enterprise. Both received significant acclaim and, notably, both led to us been offered other excellent titles that are now published. The Goatfell Murder encouraged T A Stewart to write her Scottish Canal Crimes, and The Black Cuillin led to our acquisition of The Way of the Cuillin, a superb novel by Roger Hubank, prize-winning author and perhaps the best known exponent of the mountaineering novel.’

We asked Calum Smith about his mountaineering experiences, what led him to write these books and his plans for a new book about the mountains of Arran.

The Black Cuillin

By Calum Smith

Published by Rymour Books

Your writing demonstrates a deep love of the Scottish mountains, especially the mountains of Skye. Can you tell us a bit more about how that came about and about your early experiences of the mountains?

Your writing demonstrates a deep love of the Scottish mountains, especially the mountains of Skye. Can you tell us a bit more about how that came about and about your early experiences of the mountains?

Most of my early life I was a very keen rock climber. In Scotland this could mean days, sometimes weeks, waiting for dry weather. In my case, a non-driver and constantly impoverished, it was a case of sitting it out in a tent. After several strenuous days on the hills it can be a blessing to waken up to the patter of rain on the canvas⸺a guilt-free rest day. The second day is enjoyable too; the third and fourth less so. Life becomes a routine of reading, snoozing, brew of tea, reading, snoozing, brew, etc.

Not having a car meant that everything needed for the holiday had to be crammed into a rucksack, with little space for non-essentials like reading material. You needed one book, though⸺the climbing guide which contained details of the routes, their grades, length, the first ascentionists, and ancillary chapters that covered the likes of geology, flora and fauna, history etc. This was often all there was to read on wet days, and was how my interest in mountaineering history began. The more it rained, the more I learnt about climbing in the Cuillin. I am proud to say, though, that I never succumbed to the geology section.

It was my brother who introduced me to the hills and gave me the advice I needed, while my parents provided me with an enormous amount of freedom. Along with some schoolfriends I gradually expanded my horizons: the Campsies, the Luss hills, the Arrochar Alps, Crianlarich. Often hitch-hiking, we progressed to rock climbing venues like Glen Coe and Ben Nevis; the former being especially favoured as the pubs, the Clachaig and the Kingshouse, were full of great characters and music. Then there was Skye, and, as Ben Humble would say, the ‘climbers’ Mecca’ of the Cuillin. But it was too far away, too expensive, too scary. That was until one of my schoolfriends got a car, a beat-up Mini where the front passenger could watch the miles pass through a rusty gap in the floor.

What is special about the Cuillin is that they are Britain’s only true mountains, comprised of narrow rock ridges and jagged peaks. To me it is also their location that makes them unique in Britain, the juxtaposition of rock, sea and land. One ingrained memory is descending from the mountains in the evening after a grand day, with the sun setting over a shimmering Minch, the Outer Hebrides beyond, an unforgettably beautiful scene. Another attraction of the Cuillin is that the sun does not hit the main cliffs until about four in the afternoon, and in June you can climb until midnight. This really suits me as you can have a long lie and a leisurely morning.

I have bivvied out many times on the tops⸺another wonderful experience with all the island light-houses flashing their lights at their respective rates. Early morning on the summits, in fine weather, brings Alpine-like light with an atmosphere reminiscent of what the early tourists called ‘the sublime’.

What climbing books influenced you?

Books that inspired me included B H (Ben) Humble’s The Cuillin of Skye. As a youngster I borrowed this from Partick Library; I can still recall its navy blue Corporation binding embossed with a circular stamp, ‘Public Libraries Glasgow’. Humble was one of Scotland’s first outdoor writers and his books exuded a youthful enthusiasm that was very infectious. The Cuillin of Skye was large format, unusual for a mountaineering book at this time, certainly a Scottish one, and was filled with evocative photos, especially of the 1920s and 1930s when climbers had minimal equipment, just nailed boots and ropes tied around their waists.

Around the same time, I remember reading Alastair Borthwick’s Always a Little Further, a book that belonged to my brother. I was off school with chickenpox or measles, bored, and looking for something to pass the time. I started it without knowing what it was about, misled by the obscure title. It was a revelation, a well-written but unpretentious tale of young people escaping the grime and asperity of 1930s Glasgow to discover and explore the hills and lochs of Scotland. The weekend supplements regularly list ‘Books that have changed your life’. (These selections invariably include titles I’ve never heard of, so it was gratifying recently to see one African writer choose The Argos Catalogue.) Always a Little Further would certainly be mine with its simple but profound message of the joys of the great outdoors, over the life of a ‘wage slave’ in the cities.

The Black Cuillin was a long time in the making. Can you tell us a little about the process, the sources and the people you consulted?

I was never particularly good at English at school, nor have I ever had a deep desire to write. But what I do love is research, and then putting all the bits and pieces together in some coherent form. I travelled all over Britain to visit libraries and archives. Really good fun, and often quite exciting as you don’t know what you’re going to find. I once went, by public transport, to Bangor in North Wales to look at a Cuillin pioneer’s diaries – they were totally illegible. I came back with one word for my book! (and that was in brackets).

The best writing tip I came across was, rather than initially trying to produce the near finished article, write down any relevant rubbish and make this your raw material, your starting point for the real writing, the editing. I do a lot of editing and really enjoy it – it’s like a big puzzle trying to find the right home for each part.

Your second book, The Goatfell Murder, is based in the Scottish mountains, but is a very different type of story. Can you tell us about it and what drew you to this historical tale?

After writing The Black Cuillin I wanted to compile a companion volume to another favourite venue, Arran. One historical incident of note here was the ‘Goatfell Murder’ when John Watson Laurie, a Coatbridge pattern-maker, was accused in 1889 of murdering an English tourist, Edwin Rose, on the slopes of Goatfell. I intended to devote a chapter to this well-known incident, but once I began to research the circumstances, I discovered that there was a vast amount of material that had never previously been used. There was enough, in fact, for a separate book, which became The Goatfell Murder.

I went through contemporary newspapers such as the Airdrie Advertiser, Coatbridge Express, Ardrossan and Saltcoats Herald, and created a long timeline, about a year in fact, detailing Laurie’s movements and activities on a daily, often hourly basis, just like on TV crime programmes. Again, this was really enjoyable, comparing Laurie’s own accounts with witness accounts, police statements, and those interviewed by reporters.

Laurie worked in a locomotive factory in Springburn so I researched what it was like to do that; he met Rose on the Ivanhoe steamer so I found out what I could about the vessel. I visited Laurie’s family home in Coatbridge, his haunts around town, and best of all, the site of the alleged murder on a remote part of Goatfell where Rose’s body was hidden under a boulder. (For many decades the murder, if it was a murder, was a cause célèbre, and a large cairn, complete with flag, was constructed on top of the boulder to guide tourists to the gory scene.) I even had a wee root about the heather to see if there was any evidence that had been missed!

The Goatfell Murder is unlike any other true life murder mystery in that the accused is found guilty about halfway through the book. Can you tell us a bit about the second half of the story and its account of crime and punishment in Victorian Scotland?

Most books would probably end with Laurie’s trial at the High Court in Edinburgh where he was sentenced to life at Peterhead Prison. Although I wanted to describe what convict life was like, I found next to nothing regarding personal experiences in Scottish prisons in the late Victorian/Edwardian period. There is a reason for this: few prisoners could read or write.

Among the public, though, there was a great appetite for stories about life behind bars. Journalists would meet up with convicts on their release, and pay them for an account of their time inside. These, however, were very sanitised versions as, if they were critical of the prison system, prisoners knew what to expect on their return.

Inmates at Peterhead were only allowed to send one letter of four pages every three months. They got round this by writing the letter conventionally, before turning the page 90 degrees and writing across what they had already put down. It was forbidden to talk about prison life or ‘anything beyond domestic and personal matters’. If you did, the letters were confiscated and filed as ‘suppressed letters’. It is from these that we first hear the genuine voice of John Watson Laurie. By this point readers will have already made assumptions about the central character: perhaps wayward, immature or not too bright – but with the introduction of the first person, someone more complex emerges, as in Laurie’s letters to his distraught and devastated father. The Glasgow Herald called the story of Laurie ‘one of the most remarkable dramas of crime and retribution in the judicial annals of Scotland’. I wanted to tell the whole story of the murder reflected through the experience of John Watson Laurie.

We are not alone in eagerly anticipating the publication of your history of the Arran mountains, The Hills of Arran. Can you say a little about the book and how it is similar to or differs from The Black Cuillin?

Early visitors to the Cuillin were a mixture of scientists, artists, writers, adventurous tourists, government surveyors, etc. With Arran things were a bit different. The island was seen as ‘the geological epitome of the world’ and, as such, the hills became an important location for evidence gathering in the various rancorous disputes the early geologists seemed to revel in, like the Plutonist-Neptunian debacle between the new rational scientist and the scriptural geologist trying to reconcile recent discoveries in geology with the Biblical narrative.

Reading the geology books of the day can be a tedious task. Negotiating these turgid tomes looking for something, anything, of interest, is one of the unsung services that writers provide the reader. On the other hand, primary sources like letters are full of colour and interest, where the minutiae of detail brings otherwise dull characters to life. Take the geologist Sir Roderick Murchison, whose formal writing suggests a lofty, somewhat self-important presence, but whose personal letters reveal someone more down to earth. (In the recent movie, Ammonite, it is Mrs M who has a lusty sexual fling with Kate Winslet.) Murchison wanted to study the geology of Arran, but lacked the expertise to do so on his own. He consequently asked the more experienced Adam Sedgwick if he would like to join him as mentor and travelling companion. Here’s a taste of their correspondence prior to the trip:

Murchison: ‘Dinnae forget the land of cakes, whisky, and hospitality, where I hope to act as your aide-de-camp; which having been my old trade before I took to the road, enables me to say without presumption that I am not a bad caterer’. The older Sedgwick, a Yorkshireman Dalesman, replied: ‘I am most anxious to accompany you to Scotland, and if possible will be ready by the time you mention. I think I told you that I am out at the elbows, and that this sorry condition of my garments prevents me from going to Germany. You, it seems, have lately been breech-less. So on the whole we shall exhibit good specimens of denudation.’

The Black Cuillin and The Goatfell Murder by Calum Smith are published by Rymour Books respectively priced £22.00 and £11.99.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

Nature playlist

Nature playlist

‘Light in Scotland has a quality I have not met elsewhere’ – Nan Shepherd, The Living Mountain