‘Today, all old buildings that survive in the wild solidly enough to still provide basic shelter are known as bothies. Some walkers now seek them out as others bag Munros, in a pursuit that has become known as bothying.’

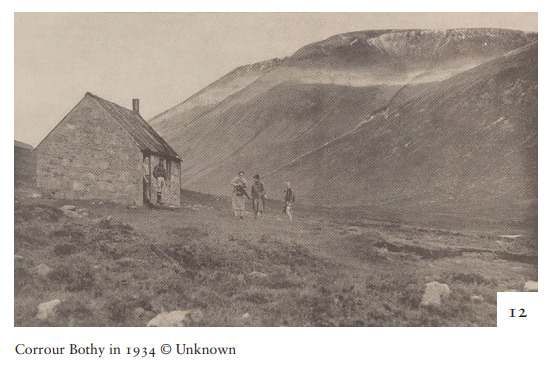

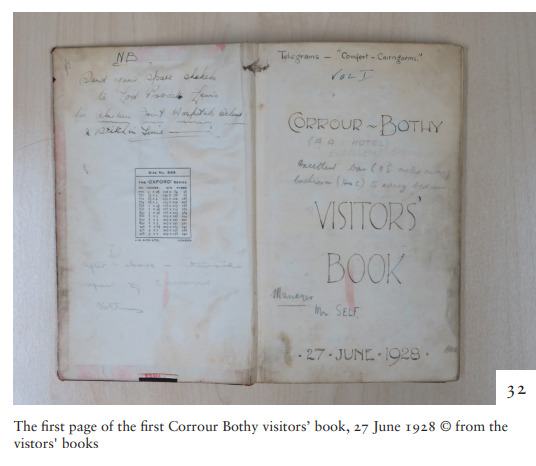

The book tells the story of the oldest and most famous bothy in the world, celebrating a century of public use in 2020. The book blends guidebook entries with historical accounts. Through guidebook entries between the years of 1928 and 2019, Storer outlines bothy life, the history of the Highlands, of hillwalking and of climbing and thereby provides a portrait of the past 100 years from a unique perspective centred on the Scottish Highlands.

Extract taken from The Corrour Bothy – A Refuge in the Wilderness

By Ralph Storer

Pubished by Luath Press

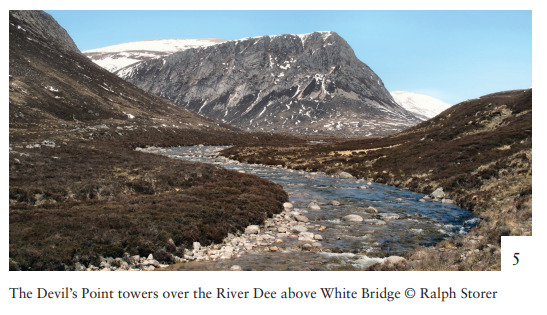

Mountain huts are a feature of many of the world’s mountain ranges, but the bothies of the Scottish Highlands are unique. Many mountain huts in the High Alps are well-appointed, purpose-built, fee-paying establishments that offer overnight accommodation half-way up mountains in order to make climbs and summit bids possible. There’s no need for such a hut system for the UK’s lower mountain ranges, although a few private huts run by clubs such as the Scottish Mountaineering Club do exist in useful locations here and there, such as at the foot of the North Face of Ben Nevis. What the Scottish Highlands do have, however, is a patchwork of old buildings that date from a time when the glens were more populated than they are today.

A tumultuous history, punctuated with clan warfare, famines and evictions, saw the Highlands cleared of much of the population in the 18th and 19th centuries, and this left countless buildings empty. Most have now been dismantled or have fallen to ruin. Anyone who has walked in the Highlands will be familiar with the broken walls and foundations that still dot the Highland landscape.

A counter-trend in some areas saw numbers of farm workers increasing in the wake of the agricultural revolution and numbers of estate workers increasing to service the great sporting estates of the 19th century. These workers were housed in what was known as a bothan, the Gaelic word for hut, anglicised to bothy. Some were stand-alone buildings, others were built as an annex to the farmhouse. They were usually of no more than basic construction and in time most of these, too, fell into disuse or ruin.

One worker from the 1850s described his bothy as ‘a hut resembling a pighouse’. Another later recalled ‘24 men crowded in a rusty corn-kiln, open from gable to gable and not above 30 feet in length’. Another remembered telling the time at night by stars seen through the gaps in the roof.

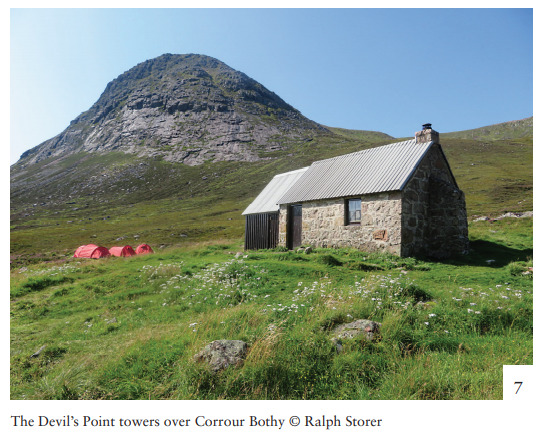

Today, all old buildings that survive in the wild solidly enough to still provide basic shelter are known as bothies. Some walkers now seek them out as others bag Munros, in a pursuit that has become known as bothying. There are also a number of more dilapidated shelters, cobbled together from bits of old building material or formed by caves or large boulders, known as howfs.

Most bothies provide no more than Spartan refuge, often with little furniture in them besides a table and a bench or chair. But they provide shelter and can save lives. Most can only be reached on foot or by mountain bike. Of the few that can be reached by vehicle, approach tracks are closed to the public. If this wasn’t the case, many bothies would by now probably have been subjected to vandalism, which is unfortunately an ongoing problem for public buildings in remote places without a custodian.

In 1965, a group of bothy enthusiasts got together to form the Mountain Bothies Association (MBA, www.mountainbothies.org. uk), a voluntary group that, with landowners’ permission, renovates and maintains bothies to make them habitable. Not all bothies are looked after by the MBA, but more than 100 are, with the vast majority in Scotland, including Corrour.

In addition to Corrour, there are several other bothies dotted around the Cairngorms, such as Ryvoan in the Lairig an Laoigh and Ruigh Aiteachain in Glen Feshie. Until recent times, they were little known outside the outdoor community. With the spread of information via the internet and social media, their locations became more widely known and in 2009 the MBA decided to share the fruits of its work by publishing a list of bothies online. Some still disagree with this move. In 2015, to celebrate its 50th anniversary, the organisation received the Queen’s Award for Voluntary Service.

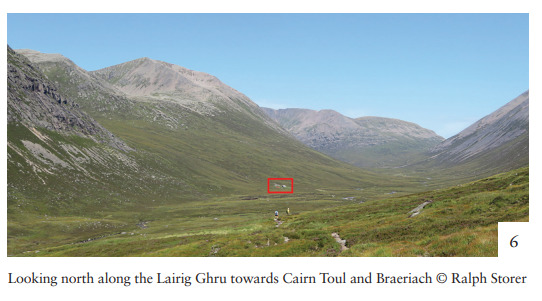

In living memory there used to be even more bothies and howfs in the Cairngorms. After the Second World War, the military built high-level shelters on the plateaus. More substantial bothies existed in the Lairig Ghru on the flanks of Braeriach (the Sinclair Hut at NH 959037) and in Coire an Lochain on the far side of Braeriach.

(Jean’s Hut at NH 981034). Following accidents and tragedies in which people died while searching for shelter, and through deterioration, all these had been abandoned or demolished by the early 1990s. Now only lower-level bothies such as Corrour remain in the Cairngorms.

The Corrour Bothy – A Refuge in the Wilderness by Ralph Storer is published by Luath Press, priced £14.99.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

A Guide to Climate Change Impacts on Scotland’s Historic Environment

A Guide to Climate Change Impacts on Scotland’s Historic Environment

‘The hottest day of the year is now on average 0.8 centigrade hotter.’

Nature playlist

Nature playlist

‘Light in Scotland has a quality I have not met elsewhere’ – Nan Shepherd, The Living Mountain