‘Canoeing slowly along the tree-shaded Blue Spring, it was the sound of frequent nose blowing on the water’s surface that made the experience particularly surreal. These loud exhalations and intakes of air were a reminder that the aquatic creatures lolling away their winter months on the bed of this naturally warm, spring-fed waterway were mammals – and they needed occasional gulps of air to keep body and soul together.’

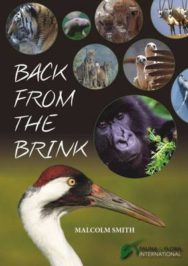

Amongst all the loss of habitat and the animals and plants in spiralling decline, it’s easy to forget that there are a huge number of positive stories too: animals threatened with extinction having their fortunes reversed and their futures secured. In Back from the Brink, Malcolm Smith tells the stories of the Humpback Whale, The Black Rhino, The Iberian Lynx, the Mountain Gorilla and many others – and here in this extract, recounts the revival of the Florida Manatee.

Extract taken from Back from the Brink

By Malcolm Smith

Published by Whittles Publishing

The Mermaid That’s No Longer a Myth

The Florida Manatee

Hunted and killed over centuries for their meat, hides and oil, by the 1950s perhaps only 600 Florida Manatees remained. Now fully protected and with a huge public following, these gentle, plant-eating giants of the inshore coastal waters of Florida attract thousands of people who come to watch them in the warm river waters they seek out in winter. Boats kill or injure many; others die from cold stress or are poisoned by red algal tides at sea. Nevertheless, their numbers have slowly increased and today there are more than 5,000 in and around the state. Further population growth is by no means guaranteed as these endearing animals still face several problems. But they are back from the brink and the people of Florida are not going to allow their manatees to slip away.

Canoeing slowly along the tree-shaded Blue Spring, it was the sound of frequent noseblowing on the water’s surface that made the experience particularly surreal. These loud exhalations and intakes of air were a reminder that the aquatic creatures lolling away their winter months on the bed of this naturally warm, spring-fed waterway were mammals – and they needed occasional gulps of air to keep body and soul together. The stream, no more than a metre or two deep, was full of grey-brown, leathery skinned Florida Manatees, the adults three metres long, their youngsters smaller.

I was with Wayne Hartley – a Florida Manatee expert with the NGO, Save the Manatee Club – canoeing the 600 metres of Blue Spring stream from its confluence with the wide, slowly meandering St John’s River to its underground source. And in this short stretch of naturally warmed water Hartley counted no less than 102 manatees basking in its warmth. Sometimes he counts over 300; that wouldn’t leave much space here even for a small canoe! Blue Spring is one of Florida’s manatee public viewing sites and attracts tens of thousands of people each winter who come to admire these remarkable and endearing animals. The manatees share the crystal clear water with a motley collection of fish – Tarpon, spotted Florida Gar and Pinocchio-like Long-nosed Gar – as well as with the occasional American Alligator. Blue Spring is one of four warm-water springs discharging into the St John’s, a river that begins its slow-flow life over an almost pancake-flat landscape in a huge, unnavigable marsh and enters the sea on Florida’s northeast coast. A vital communication route for thousands of years in a part of the US in which much of the dense forest and swamp was impenetrable, today 3.5 million people live within its catchment. Manatees have used it in winter for evenlonger. To Blue Spring from the St John’s River estuary, it’s a 240 km manatee swim each way, a swim that, in the past, would have made them vulnerable to hunters. Avidly sought after for their meat, hides and bones, they were easy to catch and kill, especially in these shallow rivers during winter. By the 1950s or 1960s, they had been reduced to maybe 600. A concerted effort to protect and nurture their population since then brought their numbers up to around 3,300 by 2001 and to over 5,000 by 2014.

The Florida Manatee looks something like a grey-coloured, chubby dolphin with a flattened, wide tail that it uses for propulsion. Manatees lack the blubber layer that allows whales to tolerate cold; in water below 16°C they weaken and die. Through the summerthey are found all round the Florida coast in waters close to shore, in winter; when sea temperatures drop, they congregate inland at natural springs and other sources of warm water, including that discharged at electricity generating power stations around the coast. Florida-wide, there are ten significant natural warm water springs manatees can retreat to in winter plus around 13 warm water discharges from power stations, although they regularly use just six of these.

Before we start canoeing along Blue Spring, Wayne Hartley measures its temperature. ‘The spring temperature never varies,’ he comments. ‘Every time it’s a constant 22.5°C. That’s how it is.’ And that’s the way the manatees like it, many of the adult females with a youngster at their side and most of them just lounging away the winter months in these clear warm waters; the adults spending a good proportion of their time sleeping while smaller youngsters occasionally suckle.

As Hartley paddles us upstream, not only is he counting the numbers of adult manatees and their calves we pass alongside as they surface for air – or those we glide silently over as they sleep beneath us on the stream bed – incredibly he is also able to almost instantly identify each adult. His database of these animals is the longest running on any group of manatees in the world; over three decades of study. ‘Jacques Cousteau [film-maker and conservationist] heard about the Blue Spring manatees and came to film them in 1970. He filmed 11 animals, the only ones here then; six we kept track of and two, Merlin and Brutus, are alive today,’ says Hartley. ‘Judith came in to Blue Spring in 1998. She had calves over the years; they were Julie, Easter, Jip, Jim, Jemal, Jinx and an unnamed calf. Judith died in 2008 of unknown but natural causes. Julie, Easter and Jim are still with us. Julie had calves over several years; they’re Jolly, Mon, Jake, Jerry, Josh, Jaco and two unnamed ones.’ He points to those he spots by name as we pootle this way and that in the canoe to check them out.

But how is it that Hartley can possibly differentiate individual manatees? Ironically, this system of recognition relies on one of the major threats to the animals themselves: boats. Collisions between manatees and boat hulls or boat propellers – if they don’t kill the hapless animal outright or inflict an injury that causes a lingering death – leave large scars on their backs or chop pieces of flesh out of a manatee’s fluke-shaped tail. Often these scars heal slowly over time; more often than not they leave permanent disfigurations in their skin, each pattern unique, thereby allowing an individual to be identified. In an assessment done from 1974 to 2011, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) found that over a quarter of manatee deaths were due to boat collisions compared with 17% attributed to natural causes.

‘When I first came to Blue Spring in the 1970s I told people that though summer was our busy season we often had 400 visitors coming to see manatees on a weekday in the winter and as many as 600 on a weekend day. That’s a joke now! With the publicity generated by the Save the Manatee Club, Blue Spring [a protected state park since 1972] gets 3,000 on a weekday and sometimes 5,000 on a winter weekend day!’ comments Hartley.

*******

For centuries, millennia even, the myth of mermaids has been an intrinsic part of many cultures worldwide. But what has this half fish, half human form to do with manatees? The answer to that is that manatees and dugongs are most likely to have been the origin of some, even many, of their reported sightings, most of them by sailors long at sea.

The first known mermaid stories appeared in Assyria about 1000 BC. The goddess Atargatis loved a mortal (a shepherd) and unintentionally killed him. Ashamed, she jumped into a lake and took the form of a fish, but the waters would not conceal her divine beauty. Thereafter, she took the form of a mermaid — human above the waist, fish below. A popular Greek legend turned Alexander the Great’s dead sister, Thessalonike, into a mermaid that lived in the Aegean. She would ask the sailors on any ship she would encounter only one question: ‘is King Alexander alive?’ to which the correct answer was: ‘he lives and reigns and conquers the world.’ This answer would please her, and she would accordingly calm the waters and bid the ship farewell. Any other answer would enrage her, and she would stir up a terrible storm, dooming the ship and every sailor on board.

In British folklore, mermaids have been described as able to swim up rivers to freshwater lakes (what mammal does that remind you of?). In one story, the laird of Lorntie went to aid a woman he thought was drowning in a lake near his house; a servant of his pulled him back, warning that it was a mermaid, and the mermaid screamed at them that she would have killed him if it were not for his servant. Not all mermaids were so nasty. Mermaids from the isle of Man in the UK are considered more favourable toward humans than those of other regions; there are various accounts of assistance, gifts and rewards. One story tells of a fishing family that made regular gifts of apples to a mermaid and was rewarded with prosperity. Just like manatees, mermaids are vegetarian!

In 1493, sailing off the coast of Hispaniola, Columbus reported seeing three ‘female forms’, which ‘rose high out of the sea, but were not as beautiful as they are represented’. The logbook of Blackbeard, an English pirate, records that he instructed his crew on several voyages to steer away from waters he called ‘enchanted’ for fear of merfolk or mermaids which Blackbeard himself and members of his crew reported seeing. These sightings were often recounted and shared by sailors and pirates who believed that mermaids brought bad luck and would bewitch them into giving up their gold and dragging them to the bottom of the sea. of course, most of them had been at sea for months or even years starved of female company and more; any apparition they encountered might have taken on a female form!

Back from the Brink by Malcolm Smith is published by Whittles Publishing, priced £18.99.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

Home of the Wild

Home of the Wild

‘I have had many animal companions in my life and all of them have touched me greatly, but the one t …

The Secret History of Here

The Secret History of Here

‘Perhaps there is co-operation as well as competition in the natural world.’