‘The dead thing’s limbs were folded, and its face looked away from the road, towards the loch. The night was silent.’

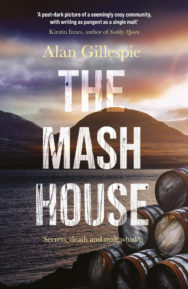

Who’s interested a page-turning mystery, set in the Scottish highlands with lots of thrills and gallons of whisky? You too? Of course you are! The Mash House by Alan Gillesie is a perfect holiday read whether you’re on the beach or curled up in a chair by the fire with a dram of your own. Enjoy this extract and remember to drink responsibly.

Extract taken from The Mash House

By Alan Gillespie

Published by Unbound

1

The cat’s brains were pink and glistening in the glow of the clear, high moon. Rivulets of blood puddled on the concrete. The dead thing’s limbs were folded, and its face looked away from the road, towards the loch. The night was silent.

Alice had been driving with the windows open, and when she hit the cat the sound of its bell tinkled noisily until it landed, but now the road was silent. The blood formed a jammy shadow around the cat’s body.

Alice pulled her car onto the verge. The Shore Road that ran parallel to the loch was wide with a good surface and quiet at this time of night. She sat on the bonnet and lit a cigarette. She always smoked when she was alone. Innes would take them from her mouth and stub them out.

There were a few houses nearby, but Alice had not lived in Cullrothes for long enough to know who the cat’s owner might be. The creature had a red collar around its neck and a white love heart on its flank. The road was dark with no street lights, and the water on the surface of the huge loch moved softly.

Alice slipped her sandals off and stretched her toes on the cold concrete as she finished the cigarette. Smoking here, polluting this clean, crisp air, felt subversive. Although it was dark and silent, she thought someone could be watching her. She pushed her hair behind her ears. It was blonde but needed a cut and a fresh bit of colour. She took a step towards the cat and looked at it again. If she had a signal she could call someone, but her phone was useless in the village. You had to get to higher ground before getting anything. She squatted and focused on the cat’s side to see if its lungs were still expanding, to see if its paws or tail might still twitch.

Nothing. She stood and looked out to the water, smoking the cigarette down to the filter, until she caught a burn on her lower lip. The loch here was endless, small ripples rising like hackles and falling against the pebbled bank. People went out onto this water in canoes at the weekend. There were fish farms out there somewhere, further along the coast, hiring up all the kids who left school without good enough grades to move away for university. When she first moved up here there had been men standing out in the loch, the water up to their chests, casting fishing lines. The tourist information kiosk sold postcards to campers and tourists of the loch glowing as the sun went down behind it. This was the village’s key attraction, along with the Cullrothes Distillery that put on tours and sold expensive bottles in the visitor centre.

Alice turned back and looked up and down the dark road. She bent and sunk the burning, fizzing cigarette butt into the dead cat’s flank, right in the middle of that white patch shaped like a love heart. She rotated the filter as it smouldered then expired, the smell of singed hair reaching her. The cat’s brains looked as though they were already drying out, the pink turning to grey, the blood congealing and settling. She gripped the cat’s hind paws and held them together in her right hand, lifting the thing up and away from her. A drooling slobber fell from the wound in the cat’s head and dangled in a thin strand to the road. Alice swung once, twice, keeping the corpse away from her dress and then released, following through onto her tiptoes, and the cat soared, rotated, twisted a little, visible only in the moonlight, and landed lightly in the loch. There was barely a splash.

When Alice was wee, a neighbour’s cat had jumped on her head and got its claws caught in her hair and pulled her crying to the ground. She had always hated cats.

Alice stepped into her sandals and returned to the car. She turned the key and the interior light came on with the engine. On the passenger seat was her teacher planner, emblazoned on the front in gold font: Cullrothes Community School. Her breath tasted of smoke. Innes hated when she smoked. Said he could taste it way back down in his throat. She rummaged in her bag until she found some mints, shifted into gear and pulled back out into the road.

2

The phone box felt small with the door closed. Its glass sides sealed Sandy in from the fresh air and it was hot and muggy. He stood with his hand resting on the receiver so that he could pick up on the first ring, knowing how loud that sudden noise would feel in the quiet of the night. He had used this phone for years when he was a child, making hundreds of phone calls to his father asking for lifts home and extra pocket money when he had ventured too far and spent everything he had on sweets. His breathing was just returning to normal after the long, difficult hike through the heather-quilted glen, his heart rate settling. His feet were sodden from losing his bearings and skirting a marsh. But driving or walking east along the A861 would raise suspicion at this time of night, long after the ferry’s last timetabled crossing to the mainland, when the roads were almost entirely empty.

The ferry was moored a little way out from the shore, its engines dead, with a few lights at the highest point of the mast twinkling. This ferry took only seven minutes to shuttle people back and forth to the mainland; after its last crossing at 8 p.m., the only way to escape the peninsula was to drive for three hours around the loch. The ferry took commuters to and tourists from the mainland, hikers and campers and caravanners turning up in their thousands every summer to ruin the beauty of Sandy’s childhood home. You felt comfort knowing that nobody else was likely to turn up in the village once the ferry was finished for the night; a sense of isolation too.

The phone rang.

Sandy snapped it up, the noise echoing around the small chamber. He glanced up and down the road, one direction leading to the ferry terminal a little way up the lochside, the other winding through the glen for some miles, back to Cullrothes. He saw nothing. Heard silence.

He lifted the receiver to his face. Hello?

Hi.

Thanks for calling.

Half past eight. Just like your message asked. This is the number for the phone box at the ferry port isn’t it?

Yes.

Who am I talking to?

I want you to buy a story from me. You do that sort of thing, right?

Depends on the story. What have you got?

I need money for it.

If the story’s good, we’ll pay. But it depends.

Sandy glanced up and down the road again. The anchored ferry had drifted a little closer to the shore, its white paintwork reflecting like a ghost on the water.

It’s about the Distillery. There’s stuff going on there. Things that shouldn’t happen. I think you could make quite a big story out of it.

Are you an employee?

I don’t want to say.

Listen, if we publish a story, we need to have proof to back ourselves up. Without photographs or other hard evidence a story’s too risky to run. It’s just something a guy’s overheard or made up. So, if you’ve got a good story about the Distillery I’m interested, but I need more information.

It’s drugs. The place is full of them. I don’t know what kind it is. Brown powder, green buds, little pale pills. I haven’t worked out how they get in. Might be by boat. Then they’re kept at the warehouse until they get picked up by the delivery lorries. Going out all over the country. I don’t know where he gets them from or where he sends them, but there’s millions of the stuff. I’ve got photographs.

He?

Donald Fleck. The boss.

Have you gone to the police?

No. I wanted to see how much it was worth. I need money for it. I’m not bothered about it, he can do what he likes. Doesn’t affect me. But I thought you could help.

And you’ve got photographs already? Hard proof?

Yes.

You work there?

Okay, I do.

I’ll need to talk to my editor. I might be able to get you a couple hundred for it. I know it’s not a lot, but I’ll need to see the pictures and clear up some details. Ask the managing director for a statement. Do you live on site? One of the cottages at Distillery Lane?

The managing director?

Yes, Mr Fleck. We’ll need to ask him to comment before we run it. Out of courtesy.

I’m not sure that’s the best thing to do.

It’s got to be done. Legal thing.

Can’t you just run the story without that? A public interest thing? You’ll sell a bunch of papers with it.

The voice on the other end of the phone began to laugh gently. Sandy tightened his grip on the receiver.

We already sell plenty of papers.

Yes, but this story, it’s a scandal. It’s huge for this area. Can’t you just run it and make your money? You don’t need to go asking Donald questions. Leave that to the police, if they think it’s worth doing.

Are you scared of him? the voice asked. Does he frighten you, Sandy boy?

He battered the receiver into its cradle, slipped out of the booth and into the blackness of the forest by the side of the road. Sandy’s heart butted against his chest and his ears roared. He turned back to the trees, which he knew so well from childhood games, and ran, his feet slapping into the mud, ran back to the village, to the Distillery, to the cottage in the lane where he should have been all night.

3

Alice scraped her hair back into a ponytail as the school bell rang. The children in the playground quietened as they lined up, and slowly the junior class came into the classroom, shrugging their schoolbags from their shoulders and dropping them to the floor. Cullrothes had an all-through school for pupils of all ages, streamed into junior and senior classes.

Good morning children, said Alice once they were all in. It was a bright and well-lit room with pictures of the children’s work on the wall with their names underneath. Colourful display boards with punctuation guidelines and the classroom rules.

Good morning Miss Green, they chanted back in unison.

Alice walked around the tables as the children settled, pulling their pencil cases from their bags and hanging their little blazers on the hooks on the wall.

A chubby boy with messy hair was still standing near the doorway, rubbing his nose.

Derek, hurry up and get your stuff out.

The chubby boy’s eyes were red, his lips chapped.

Derek, she said again, moving closer to him, and the boy struggled out of his blazer.

Settle down, boys and girls, called Alice. Come on, we don’t have all day.

The children turned and faced a statue of Christ on the cross which hung over the chalkboard. Mary our mother, said Alice, crossing herself.

Guide everyone at Cullrothes School with your kindness and understanding. Teach us to be responsible and to always help others. Lead us when we are lost, and comfort us when we are lonely. Amen.

The children all copied Alice in crossing their chests, and then turned as a crowd to face Derek. His pink cheeks were wet with tears and his hands gripped at his dirty brown hair.

Derek, said Alice. Sweetie, what’s wrong? She walked to him in quick steps and knelt down to his height.

Nothing, the boy whispered. Some of the children began to laugh.

Alice stood up. Does anyone know what is wrong with Derek?

A little girl with blonde hair put her hand up.

Yes, Ellie?

I live next door to Derek, said Ellie. He’s upset because his cat has ran away in the night.

He has not, snapped Derek.

The cat didn’t come back last night, continued Ellie. It was out all night. Him and his dad were out in the street shouting for it all morning. I heard them when I was getting my cereal.

Well, said Alice. I can see why that would upset you. But listen, sweetheart. Cats are resourceful. Sometimes a cat may stay away for days or weeks at a time before they come home. What’s your cat’s name?

Derek turned his head away from the teacher.

It’s called Hercules, said Ellie. And it’s black and white with a patch on its side shaped like a heart.

The rest of the children broke into loud whispers. Alice felt a ripple deep in her stomach and her face grew warm.

The Mash House by Alan Gillespie is published by Unbound, priced £9.99.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

Sunrise by the Sea

Sunrise by the Sea

‘The wall she had built around herself was as sturdy as that of the flat and nobody had the power to …

David Robinson Reviews: Scott-land

David Robinson Reviews: Scott-land

‘If you were writing a novel set in a Scotland in which Scott never existed, what kind of place woul …