‘”We need a better story.” Suddenly all eyes were on Peter, and he looked at Babs defiantly.’

American Goddess is a novel that explores an unstable marriage and the consequences of a post-pandemic world looking for hope from an unlikely leader. In this extract, husband and wife, Peter and Ellisha, meet a charismatic professor and her students.

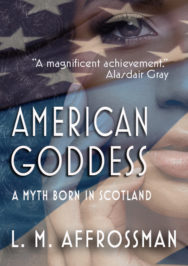

Extract taken from American Goddess

By L. M. Affrossman

Published by Sparsile Books

Her attention turned back to Zach and Deborah. ‘Where was I?’

‘The infallibility of the deity,’ Zach suggested.

Babs threw him a venomous look. ‘Indeed. What an infallible thing the deity of men has become. He’s been sucking up power for thousands of years, first the power of women then the power of all the other gods. Gods once had weaknesses, you know. They were capricious and angry and jealous. But the God of Abraham lives in a very strange, exalted place. He takes credit for all the good in the world. And when things go wrong, earthquakes, tsunamis, the death of a child, his cronies throw up their hands and say his ways are too damn mysterious to interpret.’

‘Or that it’s our fault because we displeased him.’ This again from the boy.

‘Good point. What does God have to do to get a bad press?’

‘Yes, but isn’t— I mean …Well I think religion is a comfort,’ Deborah said nervously. ‘I mean as a Christian I think that’s the point of religion. To give comfort.’

‘Yes. Yes. That’s always the argument for religion,’ Babs answered. She was lighting a tipped cigarillo despite the sign that clearly read No Smoking above her desk. ‘But for every bit of comfort, how much is there in the way of guilt and fear and sheer inertia to change things? What about Galileo or the American reporter on his knees awaiting a beheading or the poor devils dragged up Castle Hill to be burnt as witches? How much comfort would it be to feel the flames licking about your feet?’ Babs banged her fist down on the table, startling everyone and sending an apple-shaped penholder rolling from the desk. Ellisha bent to pick it up.

‘Dr McBride,’ she said in a soothing voice. ‘Perhaps I should make some tea.’

‘No need. Brought my own.’ After some fumbling about under the desk, she produced a thermos and poured herself a generous measure of a liquid clearly unrelated to tea. She took a gulp then a long drag from the cigarillo. An ectoplasmic cloud of smoke escaped from her mouth. There was something compelling about her sheer hauteur, an insouciance that bordered on the negligent. How on earth does she manage not to set off the smoke detector?

He realised that she had caught him looking. Her gaze wandered up towards the nicotine stain around the detector then back to his with a conspiratorial twinkle. For an instant he felt she was trying to tell him something. But she shrugged and turned back to her students.

In a calmer voice she continued, ‘Our young friend here, Zachariah, doubtless with fewer hairs on his pubes than he has on his chin’—Zach turned scarlet—‘has struck at the heart of the problem. Why are those men and women, with their faith in God their father, so afraid to die? What could be lovelier than to return to the arms of one’s own maker?’

‘Perhaps their faith isn’t strong enough?’ Deborah suggested timidly.

‘Yet this is what they BELIEVE! They fight wars over it, sacrifice their children, lie, murder, rape in its name. A few ghastly ones even go round forgiving everyone. But always, when the darkness nears, they rage against the dying of the light.’ She held up a hand and waved off a protest from Zach. ‘Yes, yes. There are always a few exceptions, the saints, the martyrs, the suicide bombers. But a drop of deadly nightshade in an ocean does not change the ocean.

‘So how do we explain this?’ She paused and looked round the table. The students avoided her eye.

Babs opened her desk drawer, produced an ashtray and stubbed out the remains of the cigarillo. It was a gesture of disgust and everyone knew it.

‘We explain it,’ Babs said in her stinging nettle voice, ‘by showing that the godhead is incomplete. We’re missing something.’

Biting her lip, Deborah ventured, ‘Is it the Goddess? The feminine side of religion?’

Babs drank heartily from her cup then, smacking her lips together, set it down. ‘Perhaps. The world has been too long under the influence of men. But the Goddess isn’t some sort of sticking plaster to mend mankind’s woes.’ She glanced sharply at Ellisha as she said this, revealing that she had recognised her from the start. And, with one of those unanticipated veers of consciousness, she demanded suddenly, ‘And what do you believe, hmm, daughter of a Sanskrit dream? Do you imagine, somewhere deep within you, resides the glassy essence of a soul? A measure of the divine suffice to make the angels weep?’

‘I—’ Ellisha ran her tongue over her bottom lip. ‘I don’t know.’ Clearly, she would have liked to have left it there, but Bab’s headlamp eyes left no scope for concealment. A little expulsion of air, a squirm of her shoulders. ‘I wouldn’t say I believe in nothing. But you’re right. I don’t have a strong sense of belonging to any particular faith. I’ve never found anything that I could really hold on to.’

‘Apart from your rock? Your stone man.’

‘Apart from Peter, yes.’ She darted him a quick, loving look that moved him and made him feel despicable at the same time. Babs was pouring herself more ‘tea’. ‘But you’ve never felt touched by the unseen hand? No thrill of religious experience? The magnum sacramentum hasn’t tingled in your veins?’

Ellisha wrinkled her nose. ‘I don’t—’

He could feel her gaze, knew she was appealing to him. What do you think, should I tell? But he couldn’t look her in the eye, and he had no sense that this was a turning point or that Babs’ words were weighted. After a moment, he saw her shrug then square her shoulders. ‘When I was thirteen I was struck by lightning.’

Babs put her flask down. ‘What do you recall?’

‘Not much. It was a beautiful July day. No wind. Clear blue sky.’

‘Is that possible?’ Deborah asked.

‘Oh, it is.’ Babs had hunched forward, chin clasped between her bony fingers. ‘Lightning can travel over twenty miles from where the storm is. And you would have no clue it was coming.’

‘I didn’t,’ Ellisha said, with a laugh. ‘I think I remember a crackling sound. Then I couldn’t see anything but white light for a few seconds. I guess I passed out. Because I don’t remember anything else until I woke up at home, with the doctor examining me.’

‘But you made a full recovery?’ Babs was studying Ellisha as though she was a striking artefact unexpectedly revealed by blowing sands.

‘Mostly. You’re never really okay after a lightning strike. I get headaches and sometimes I see things in my peripheral vision, shadows, flashes, that sort of thing. On the upside, I have an amazing Lichtenberg figure on my back.’

‘A kind of scar?’ Zach asked.

‘Yup. The capillaries got fried under the skin. Sometimes they fade. But mine is still here all these years later. I guess it’s part of me now.’

‘When you were thirteen,’ Babs repeated ruminatively. ‘You’re certain?’

‘Day after my birthday. You don’t tend to forget a present like that.’ Her brow crinkled. ‘Why, is it significant?’

‘It depends. Had you started your menses?’

‘Now, wait a minute!’ Peter jumped to his feet. Things were getting out beyond a joke. But Ellisha put out a restraining hand. She seemed fascinated. A mongoose caught in the thrall of a python. Or perhaps, he thought uneasily, a pythoness.

‘I’d started the week before. It was kind of a big deal because I was first out of my friends.’

‘I see. I see. A moment of transition. A rite of passage. Mutatis Mutandis if you will. Plenty of resonances in the mythic scheme of things. Lightning is divine. It purifies. Herakles, Asclepius, Semele were all struck by holy fire before they were deemed worthy of heroic status. The Incas laid out child sacrifices on mountain peaks to be struck by lightning because they thought it made them divine. All are mortal before the touch of the celestial.’ She took a long meditative sip from her cup. ‘The gods singled you out.’

Ellisha laughed. ‘I don’t believe in the gods.’

‘Immaterial if they happen to believe in you. But, of course, I use the term figuratively. Gods is just a word for opening up the dark places in consciousness. Mythology, that’s the key to everything. Ignis Dei.’ She rounded, without warning, on her students. ‘Ignis Dei. No idea what that means, eh?’

Her smugness was irritating. Feeling side-lined, Peter racked his brains for a pithy putdown. But his schoolboy Latin wasn’t up to the task. Dei, something to do with God. But Ignis? Ignorant? Ignoble? Ignominious? Nothing quite fit.

‘The spark of God maybe?’

Ellisha had spoken softly, so softly that Peter wasn’t sure she had spoken at all, but Zach slapped his hand on the desk. ‘Of course. I was thinking fire. But ignis in the sense of ignite.’

Babs sat upright, the reanimated corpse in a horror movie. She glanced narrowly at Ellisha, her face a peculiar mixture of anger and fear. ‘Who told you? You didn’t get that on your own.’

Ellisha laughed gracefully. ‘Why is it no-one believes that Americans can know Latin?’

For a tense instant, things might have gone either way, but then Babs recovered herself. She turned back to her students, swerving off in a new direction. ‘Religion has had millennia to create a satisfying system of belief. Yet the best the great theological minds of the world have come up with so far is God loves us, which is, of course, in patent contradiction to everything the universe is telling us. So, what’s missing? What do we really need?’

‘More sex,’ Zach suggested.

‘A man’s answer.’

He came back with, ‘No more discrimination. If we all learned to see each other as equals there might finally be peace in the world.’

‘Terrible idea,’ Babs snorted. ‘The purpose of religion is to make people feel special, unique, chosen by God. Without discrimination there is nothing to separate the elect from the herd. Humans will forgive their fellows all sorts of sins; theft, war, destruction. But not the sin of equality. It stifles us. Petrifies us. Not in the sense of filling us with fear, but the old use of the word. Same root as stone-man here. Petra, Latin for rock or crag. Literally to turn to stone, to be inert, paralysed.’

‘We need a better story.’ Suddenly all eyes were on Peter, and he looked at Babs defiantly.

‘Ah, our stone-man has it.’

‘What do you mean, Peter?’ Ellisha asked.

What did he mean? For an instant intuition had flashed inside his head, brilliant, blinding. But now it was gone. He stumbled over his tongue, trying to mould the heavy clods of words into a recognisable shape. ‘A religion needs to tell a story, to … to appeal to some forgotten longing buried deep down in the subconscious.’ It was hopeless. He was using clay to depict light, but Babs was pleased.

‘That’s it, Stone-man.’ She gave a rasping, smoker’s laugh. ‘Humanity loves a story. Give men philosophy and they’ll learn to think. Give them a compelling mythology and they’ll change the course of the stars. Forget sex. Narrative’s the real generative force guiding mankind. It wasn’t a foetus the Angel of the Lord deposited in Mary’s womb. It was a legend. Fons sapientiae, verbum Dei, as they say.’ She rolled an eye towards Peter. ‘Get your wife to translate that one.’ She began to cough, a deep, dragging sound, like the sound of the tide draining over gravel. The coughing went on and on. She banged on her chest with her fist several times to no obvious effect. Ellisha jumped to her feet. ‘I’ll get water.’

Babs swatted a hand at the air to indicate that it wasn’t necessary, but Ellisha had already gone. Peter watched, half in horror, half in fascination until the spasm wore itself out and Babs relaxed.

‘Fine now. Just something caught at the back of my throat.’

Peter nodded. From the corner of his eye, he noted that the students were trying surreptitiously to clear away their things. Babs noticed it too. ‘Yes, yes. Run along, children. You are in grave danger of having a thought enter your heads.’ She was pouring herself another drink from the flask. Suddenly she slammed the cup down, sending a little tsunami of liquid across the desk. ‘Don’t think I don’t know what they ask you. What’s the old witch up to, eh? What’s she cooking up behind closed doors? Ignis Dei. That’s what they want to know. Ignis Dei! But the old witch won’t tell.’

The students gave a last frightened glance at their mentor then fled the room. Babs looked into the dregs of her cup then said in a softer voice. ‘Old witch, one of their kinder nicknames for me.’

American Goddess by L. M. Affrossman is published by Sparsile Books, priced £10.99.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

Tenement Kid

Tenement Kid

‘She’s a hell raiser, star chaser, trail blazer Natural born raver, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah’

Blood and Gold

Blood and Gold

‘She heard of talking chickens, eagles with sparkling, vibrant feathers and a magic needle to whom t …