The Many Worlds in Edinburgh

‘In fact, I would argue a single, unitary Edinburgh doesn’t exist. What you have are multiple Edinburghs, grosstopically linked (to use a China Mieville formulation), different cities existing within the same space but out of sync spatially and even temporally.’

The Library of the Dead is the first novel in T. L Huchu’s Edinburgh Nights series, and will show you the city in an entirely new and fantastical way. Here, Jeda Pearl discovers the influences that fed into T. L Huchu’s writing.

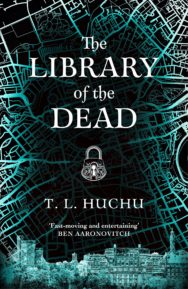

The Library of the Dead

By T.L. Huchu

Published by Tor

Content warning: death

With a bevy of entertaining and disturbing supernatural characters; a dystopian near-future Auld Reekie; and a plucky, young, ghost-talking detective named Ropa at the centre, The Library of the Dead by T. L. Huchu is an unflinching rollercoaster ride of a novel.

Ropa Moyo is a decisive and cynical teenager, who dropped out of high school so she could contribute to the household bills. Walking the outskirts of Edinburgh and educating herself with pirate podcasts, she plies her trade relaying messages from the dearly departed to their living descendants, occasionally performing exorcisms and helping spirits move on to ‘the land of the tall grass.’

We follow Ropa as she traverses the spectral everyThere, gains access to an elite occult library and sleuths through the stinking streets of Edinburgh trying to find missing children. Although she drops quotes from Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, Ropa has to evade and deal with some pretty terrifying beings. I spoke with Huchu to delve into Ropa’s Edinburgh and her extraordinary world.

Set in an eerily familiar Edinburgh, the effects of climate change and difficulties faced by much of the population – severe economic inequality, police brutality, corruption, exploitation – are simply facts of life and our protagonist Ropa’s environment. Did you originally plan to set the book in this near-future Edinburgh or did the setting and the related themes of inequality happen organically?

Every book has numerous moving parts that serve the whole and the setting is a critical component of that. It serves a greater purpose than is often paid attention to. A story that works excellently in twentieth century Harare may not necessarily play out to the same effect in twenty-first century Edinburgh. What you see in The Library of the Dead is a ‘third world’ Edinburgh, which doesn’t make much sense until you realise that prior to the Union of 1707, before Scotland benefited from the global plundering of the British Empire, it was the poorest nation in Western Europe. Therefore, this setting is designed to be jarring for the reader and to make them realise that in this universe the advances Scotland has made over the last 300 years are in the process of reversal. The chickens have come home to roost, in a sense. The book’s opening scene is in a house the historian Thomas Carlyle honeymooned in. This serves as an overt signal to the reader that we are telling a history of the future — the honeymoon is over.

With Ropa, her family and her friends Jomo and Priya, you’ve turned the idea of who gets to claim Scottish identity on its head. This is subtly and beautifully done – the streets of Edinburgh feel inseparable from Ropa and there are no ‘Where are you really from?’ moments. Her Shona heritage, culture and language are also woven with Gaelic, Scots and local slang. How deliberate was exploding the current assumptions around Scottishness and did your experience as a Black person living and working in Scotland influence these aspects of the culture in the book?

In a book like this, I suspect people would expect the characters to question their identity. Identity quests are, after all, an entire genre in their own right, and you’d be hard pressed to find a contemporary novel with a brown character in the west where the identity game isn’t playing out. But when I wake up in the morning, I don’t look in the mirror and think, ‘Oh my God, I’m Black. How did that happen?’ This is my default position, my factory settings, as it were. I choose to express my characters in terms of their core characteristics. Ropa is a strategist and a leader, Priya is an adrenaline junkie, Jomo is a beta male and insecure. The book is character driven and the characters take their heritage for granted, which I think is the way it should be when you’re a teenager. Because of this, what, I hope, you end up finding is that there are so many layers to their personhood, which I think is ultimately that which is universal about human beings.

Ropa knows Edinburgh better than any taxi driver! Did you regularly walk the neighbourhoods and landmarks featured in the book?

Edinburgh is such a small city and I’ve tramped through it for over fifteen years now, but each time she surprises me with something new. Most people think the historic centre of Edinburgh is all there is – that and a few touristy spots like Cramond or Portobello. You don’t really know this place unless you’ve been out to Wester Hailes, or Niddrie, or wound up at a random party in Liberton, or took the wrong bus and ended up in Trinity. If you wander with your eyes open you will see the city change with the seasons, old buildings torn down, new housing developments going up, businesses shut down and new ones taking their place. Edinburgh undergoes constant evolution – she is never the same city two days in a row. In fact, I would argue a single, unitary Edinburgh doesn’t exist. What you have are multiple Edinburghs, grosstopically linked (to use a China Mieville formulation), different cities existing within the same space but out of sync spatially and even temporally.

The cast of ‘deado’ ghost characters were really entertaining. Did you spend a lot of time in Edinburgh’s graveyards?

There’s a lot of fascinating history to be unearthed in those old graveyards. Reading the headstones will teach you things you never knew about life, love and loss. These are peaceful places with interesting flora and fauna. But, ultimately, when you visit the graveyards of Edinburgh, you’re confronted with your own mortality, which is what all great literature is really about.

Ropa can communicate with deados through playing her mbira and there are references to Shona and Zimbabwean music throughout the book. Do you play the mbira and is it part of your spiritual practice? Who are your top five mbira musicians to listen to?

I peaked at playing the triangle in nursery school and my sense of timing and rhythm is rather poor, so I don’t play any instruments. I’m a cultural Catholic hovering between agnosticism and atheism, but I have an interest in spirituality because of how central it is to the vast majority of people I share the planet with, including my own family. I believe it exists as an attempt to answer the really important questions about the nature of existence which plague us all, and so one cannot dismiss it outright. The mbira plays a central role in traditional Shona religion and there are many fine musicians who employ it in their craft. If I want to listen to a more traditional sound that draws deep from the culture, I turn to Mbuya Stella Chiweshe, Sekuru Gora, and the outstanding folk ensemble Mbira DzeNharira. If I feel like listening to a more contemporary sound, then I turn to the late Chiwoniso Maraire and the dazzling Hope Masike – they make it fresh and cool.

With nods to disturbing elements, such as women and girls being permitted to carry knives up to six inches long for self-defence, plus references to the scrap metal rush and times before and during the cataclysm, Ropa doesn’t hold back on the realities of living in her world. How important was it to you that these aspects weren’t glossed over and that Ropa would just get on with living her life (while investigating why kids are going missing)?

Ropa is your archetypal reluctant hero. She’d rather be getting on with her life than chasing villains around Edinburgh. And so, she is immersed in the day-to-day problems of the world she lives in. This is not Bruce Wayne going out to kick arse and then retreating to his comfortable mansion after the deed is done. For Ropa Moyo, heroism comes at great personal cost because her life is precarious, she lives from hand to mouth. And because she is from the underclass, bearing the brunt of the reality she lives in, these problems are an unavoidable part of her quotidian experience. For her there is nothing special about these things. That is why her tone is very matter of fact.

As well as funny and poignant moments, there are some chilling supernatural experiences in the book. Does this come from a personal tradition of folklore or storytelling and what folklore traditions inspire you?

I draw from so many sources, it is hard to even keep track of it all. If you know the history of Edinburgh, you will know there’s a lot of spooky shit that’s gone down through the ages. But because of Ropa’s heritage she is able to fuse this stuff with things she’s learned from her nan who is Zimbabwean. Some of the stuff I made up for myself, e.g., the Midnight Milkman. . . or did I? RIP Sean Connery. The spooky house in the novel came from a strangemare I had a few years ago. Greek mythology, which I’ve been interested in since primary school, also plays a very important role in all of this. And so, when you play around with all these things you, insha Allah, come up with something fresh, maybe even original.

Maternal bonds run deep throughout the book and, The Library of the Dead is dedicated to your mother, Josephine Huchu. Would you be open to sharing how your mother inspired and still inspires you?

Everything I am today is because of her. I work with words, but they are inadequate as a medium to convey anything truer than that.

Can you share any information about book two in the series?

Book two is currently on the hob. It’s titled Our Lady of Mysterious Ailments and you can expect even more thrills, unearthed histories, villains, and changes in Ropa’s life! Anything else about this manuscript is currently only accessible to high level security cleared spooks at GCHQ and, begrudgingly, the NSA — what can you do, hey?

Which Scotland-based Black writers and writers of colour are you excited about right now?

You’ve got very established authors like Zoe Wicomb and Leila Aboulela working in literary fiction. Or if you thinking of tartan noir then you want to read Leela Soma, author of the brilliant Murder at the Mela. But I also feel that beyond the writers of colour already working here, publishers like Canongate who have great editors like Ellah Wakatama Allfrey are going beyond that to publish exciting diverse authors from around the globe. From that catalogue alone I’ve already read Taduno’s Song by Odafe Atogun, A Tale for the Time Being by Ruth Ozeki, Stay With Me by Ayọ̀bámi Adébáyọ̀, and I’ve got Courttia Newland’s A River Called Time on my bedside table. It’s this sort of mix that fills me with hope for the future of literature in Scotland.

Jeda Pearl Lewis is a disabled Scottish-Jamaican writer and poet. She’s performed at StAnza, Event Horizon, Inky Fingers and Hidden Door and was awarded Cove Park’s Scottish Emerging Writer Residency in 2019. Her writing is published by Black Lives Matter Mural Trail, New Writing Scotland, Not Going Back to Normal, Tapsalteerie and Shoreline of Infinity. @jedapearl jedapearl.com.

T. L. Huchu is a writer whose short-fiction has appeared in publications such as Lightspeed, Interzone, AfroSF and elsewhere. He is the winner of a Nommo Award for African SF/F, and has been shortlisted for the Caine Prize and the Grand Prix de L’Imaginaire. Between projects, he translates fiction from Shona into English and the reverse. @TendaiHuchu

The Library of the Dead by TL Huchu is the first book of the Edinburgh Nights series, and is published by Tor, priced £14.99.

The Scottish BAME Writers Network (SBWN) provides advocacy, literary events and professional development opportunities for BAME writers based in or from Scotland. SBWN aims to connect Scottish BAME writers with the wider literary sector in Scotland. The network seeks to partner with literary organisations to facilitate necessary conversations around inclusive programming in an effort to address and overcome systemic barriers. SBWN prioritises BAME-led opportunities and is keen to bring focus to diverse literary voices while remaining as accessible as possible to marginalised groups.

Web links: Website | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter | Newsletter

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

Eat Bike Cook: Food Stories and Recipes from Female Cyclists

Eat Bike Cook: Food Stories and Recipes from Female Cyclists

‘There is no cream in a classic carbonara but its addition is merited by any cycling cook looking to …

Islands of Abandonment

Islands of Abandonment

‘But over time, species accrue, bed down. And now, the bings come to act almost as an archive of bio …