‘The book gives a voice to a girl forgotten by history’

I Am Not Your Eve is a polyphonic novel of Teha’amana, Tahitian muse and child-bride to Paul Gaugin, from her point of view conveyed through the myths and legends of the islands. Author Devika Ponnambalam talks to BooksfromScotland about the debut novel, route to publication, and what lies next.

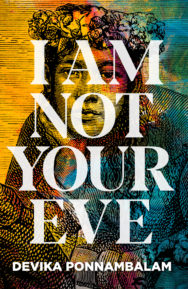

I Am Not Your Eve

By Devika Ponnambalam

Published by Bluemoose

Could you give our readers a wee summary on what to expect?

This is a book that defies narrative convention, whilst telling a story that has never been told. This is the story of Teha’amana, who became the lover and muse of Paul Gauguin on his first trip to Tahiti in 1891. The book gives a voice to a girl forgotten by history. It also incorporates a host of other voices, which lead back to the main character.

What was it that drew you to tell this story?

It was Gauguin’s masterpiece that lies at the heart of the narrative and from which everything revolves: The Spirit of the Dead Keeps Watch. I first saw the image in a magazine and it was the painting that drew me in. I immediately connected with Teha’amana’s image as a woman of colour. I wanted to know who Teha’amana was and what had been her story, but what I found out was minimal. I understood from the article in the magazine that Gauguin had died of syphilis. It made me more determined to create a narrative for her and a truth. It became important to me to tell the story buried beneath Gauguin’s Art and his journey, which has been glorified and presented to the world through his diaries, letters, and biographies.

The novel features the voices of Teha’amana and of Paul Gaugin’s daughter, Aline, through her diaries. How did you tackle juggling the voices of these characters?

Aline’s voice came easily – innocent, child-like, and at times playful – revealing her character through diary entries made it more immediate. It was a channel through which she could express her thoughts – her conflict was clear – she had an unfulfilled longing for her father and his return to Europe. It was Teha’amana’s voice that took longer to figure out. I grappled with it for many years and the conflict in her relationship with Gauguin. How would she feel about sleeping with a man who was nearly three times her age? It was a complex subject matter. I wrote her in the third person for ages but it was only when I wrote her in the first person, addressing Gauguin directly, that it all came together. At times in the book, it is as though she is looking back at her version of events. Even though Teha’amana was a ‘child’, she had to speak with wisdom and lyricism for it to work in juxtaposition to Aline’s.

As well as exploring themes of power and colonialism in your novel, did writing the novel make you think about the role of the muse?

I thought about the painting being painted from Teha’amana’s point of view and what that meant to her. She would have been bored having to sit for Gauguin day after day, and she would never know people’s reaction to the ‘work’ or its value. She would not have understood the importance of the role of muse to the painter. Even though she was a still a girl in our eyes, she would have been prepared by her community to take on the role of the wife, partner, lover, at that age. The finished painting was shipped off to another part of world, and the way she was ‘seen’ in Europe – as a brown nude not considered the epitome of beauty but the subject of curiosity – she would not have known that. I explored these ideas through a third person voice because they were important to me. She does, however, consider the role of the muse (in her own way) through the postcards that Gauguin pinned up on the walls of his hut for inspiration. I explore this through the imaginary conversation she has with Manet’s Olympia, whose image hangs above the doorway.

Paul Gaugin’s art is an influence on the novel. Did you have other inspirations behind writing the novel?

Myths and legends form an intrinsic part of the novel. Teha’amana’s story is intertwined with the stories of ancient characters that belong to Tahiti’s dramatic landscape and its sister islands. I wanted to create something truly mythic that worked as a whole, combining the old world and the new. And of course, other paintings influenced my writing, like Dorothea Tanning’s ‘Tableau Vivant’ and Pieter Bruegel’s ‘Hunters in the Snow’. I wanted to create my own reference points, as well as Gauguin’s. My filmmaking background also had a huge influence on the novel’s narrative structure. Some chapters are presented as a brief exchange of dialogue between two characters. The novel moves back and forth in time like a Nicolas Roeg film.

You have worked in film and television, other visual mediums. How do you view the relationship with the visual arts and literary art? What do you feel are their important distinctions or similarities?

There is definitely an overlap (for me) between writing for film and writing fiction. They inform one another. I’ve tried, on numerous occasions, to turn the story into a script but British film producers couldn’t identify with that world or found it too ambitious for a first feature. And there was always so much more I wanted to say. Fiction allowed me to enter Teha’mana’s inner world more readily and go anywhere I wanted to go. I have, however, made a short film, which takes snippets of narrative from the book to tell Teha’amana’s story in the form of a voice-over. A film requires its own narrative structure and is a team effort. It’s not just about your vision. The initial script is usually unrecognisable at the end, after the final edit. Shot entirely on location (by Graham Clark) in Tahiti and edited back in the UK (by Angela Leskovics), the film ‘Spirit Of The Dead’ can be viewed here.

But I think ultimately writing for film is harder because one always has to consider the budget, the audience, the producers, whereas in fiction, I don’t have to consider anything but the voice, make no compromises, just tell the story that needs to be told. I lean more towards the visual and the surreal, and fiction allows me to transition from one world to another, without having to consider the practicalities.

This is your debut novel. How have you found your journey into publication?

The journey to publication itself was quick but the writing took 17 years. I lived in London for 10 years after my MA (where I began writing the book) but it was not a productive period. It was only when I left London and came to live in Scotland that I found the space, time, and opportunity to finish the book. Creative Scotland gave me a research and development grant, which enabled me to travel to Tahiti to put all the pieces of the book puzzle together. This was the turning point for me. The book is in the same form as it was when it was submitted, first to my agent, then to my publisher. I am grateful to the both of them for not altering my vision in any shape or form. They believed as passionately as I did about getting Teha’amana’s story out into the world.

Other than promoting I Am Not Your Eve, what’s next for you?

I am in the middle of writing my next book, which I’m really excited about. It spans the 70s, 80s, and 90s and tells the story of an Indian family, and their journey from India to South Asia, and the UK. Told through the eyes of the daughter, Uma, it is a tale of migration and disintegration, exploring themes of identity and belonging within Indian patriarchy and British nationalism.

I Am Not Your Eve by Devika Ponnambalam is published by Bluemoose, priced £12.99.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

The Book… According to T. L. Huchu

The Book… According to T. L. Huchu

‘I have fond memories of my childhood, tucked in bed with my mother reading A Kiss For Little Bear b …

All the Way Home

All the Way Home

‘I wis jist aboot awa when sumbdy I didnae ken flopped doun aside me in the daurk, and I woke up aga …