‘Despite the hardships and horror, the fear and danger present in the novel, Stuart has captured what it is to love, in all its complex glory – and more importantly, what it is to hope.’

The highly anticipated follow up to Douglas Stuart’s Booker Prize-winning Shuggie Bain is finally here, following the moving story of the dangerous first love of Mungo and James, two young men sitting on opposite sides of Glasgow’s Protestant and Catholic divide. Nasim Asl reviews Stuart’s latest for BooksfromScotland below.

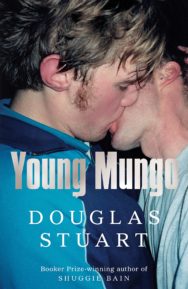

Young Mungo

By Douglas Stuart

Published by Picador

Two years after shaking the literary world and winning the Man Booker for his debut novel, Douglas Stuart’s highly anticipated second outing, Young Mungo, has arrived. It’s an accomplished, moving, and touching story of class, loneliness, addiction, violence, queerness and love, and cements Stuart’s status as one of the most gripping fiction writers of our moment.

From the outset, his language is laden with poetry and heady with metaphor. Stuart recreates the city of his youth in intricate detail, so that both Glasgow and the characters that inhabit it rise from the page in alarming vividness. So incredible is the realism of Stuart’s work, so natural is his use of dialect in dialogue, that it’s easy to forget Young Mungo is a work of fiction.

Given their similar subject matter, it’s inevitable that considerable comparisons will be made between Young Mungo and 2020’s Shuggie Bain, especially when Stuart’s debut moved so many. Both stories follow teenage boys coming to grips with their homosexuality while navigating life in a Glasgow scheme and a family crippled by alcoholism. The eponymous Shuggie and Mungo do feel as though they’re made from very similar models, at least at first. They both come to realise their own sexuality as their narratives progress but struggle in the meantime with notions of gender and what it means to be a man as they navigate their loneliness. Mungo is undeniably a victim, but there’s less victimhood in his construct. He’s bolder, less alienated, and frankly more likeable than Shuggie.

Young Mungo deals with violence in some of its most extreme forms. It’s upsetting, graphic and unconscionable at times, but Stuart uses it to unflinchingly address and confront the acts of aggression that too often are faced by queer people, and the prejudices faced by members of the community – as well as to highlight the impact of sectarianism on communities in Glasgow.

It’s a sign of Stuart’s masterful craft that Young Mungo doesn’t feel at all like a retelling of its predecessor. There’s a freshness of plot, structure and characterisation that will leave those already familiar with Stuart’s work feeling fulfilled and will punch those new to him straight in the gut. Young Mungo feels less bleak. It’s harrowing, heart-breaking, and graphic, and the world of Young Mungo is still cruel, but there’s a lot more love in this version of Glasgow. There’s hope that the characters and their patterns of violence and neglect can be broken.

Young Mungo is a coming-of-age story. Narratively, it’s gripping – the plot fluctuates between a present where Mungo has been sent on a fishing trip with two strange men his mother knows, and the recent past in which Mungo falls in love. It’s this love between Protestant Mungo and Catholic James in ‘90s Glasgow that drives the events of the novel, and their every interaction is rich with tension. No wonder then, the boys dream of a world and a future together away from their scheme, where they can live without fear or threat.

While the plot differs, there are resemblances still between Young Mungo and Shuggie Bain, in the alcoholic single mother, and the relationship between siblings. Mo Maw, Jodie and Hamish all jump off the page and resist being typecast by their creator’s previous work. They’re fully fleshed out characters, with their own clear identities, motives and struggles, and there’s a depth, complexity and warmth to the family that was missing slightly in Shuggie Bain. Stuart has created a family that is unwaveringly and depressingly human, a family with flaws and conflict, but ultimately a family that has a future that the Bains did not. It’s this touch of agency that weaves possibility into Young Mungo. These characters are in control of their actions and their destiny and feel less like victims of their unfortunate circumstance.

Some of the novel’s most moving scenes are those between Mungo and his gang-leader brother as Hamish tries to mould Mungo in his own image. Their interactions are charged, tense and revealing, but humour flashes between them too. Especially heartfelt is the relationship between Jodie and Mungo. I found it more developed, more compelling, deep, and nuanced than that between James and Mungo. Still, we can’t help but fall in love with the young couple too in the doocot – the images of Mungo cradling James’s pigeons in his hands are clever nods by Stuart towards the tales of St Mungo.

There are other powerful images connecting Mungo to his namesake. So too, do the themes of justice and faith, and Glasgow – which operates as a character in its own right. The streets curl across the pages as Mungo wanders them. Young Mungo is another glorious tribute from Stuart to the city, but he doesn’t sugar-coat the violence that sectarianism has been responsible for. Through both Mungo and James’s relationship and Hamish’s Protestant gang waging war on Catholics, Stuart explores the impact of this division, one that still echoes in Glasgow today, while lamenting the loss of industry and its impact on multiple generations.

Fittingly, I finished Young Mungo while returning to Glasgow by train. As our cities blurred in my head and I reflected on what I’d just read, the woman sitting across from me had noticed what I was reading and asked me for my thoughts. She loved Shuggie Bain and was clearly still affected by it. This is something I’ve been struck by since Stuart’s debut was published – I’ve never met anyone who has read it and not been desperate to talk about it. His work is poetry, it’s tender, it’s beautiful in isolation, but I think it strikes a particular chord for people who know and love Scotland and especially those who know and love Glasgow.

Readers see their families, their queerness, their struggles, and their city revealed on the page by Stuart. It’s tough but rewarding in equal measure. In both his books, Stuart tells stories that have been missing from the canon. He clearly cares about the world he’s creating, a world filled with characters and protagonists that are hard to forget, none more so than Young Mungo. Despite the hardships and horror, the fear and danger present in the novel, Stuart has captured what it is to love, in all its complex glory – and more importantly, what it is to hope.

Young Mungo by Douglas Stuart is published by Picador, priced £16.99.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

The Arena of the Unwell

The Arena of the Unwell

‘Am I paranoid, or are they really after me? I feel like we’re being hunted in here. This song has t …

Q&A: Jim Byers and Jonathan Trew on Edinburgh’s Greatest Hits

Q&A: Jim Byers and Jonathan Trew on Edinburgh’s Greatest Hits

‘I think one of Edinburgh’s strengths is its creativity and eclectic spirit.’