‘Supporting bilingualism is crucial in allowing a child to connect with that side of their heritage and culture.’

Amy Moreno writes an exclusive piece for BooksfromScotland about growing up bilingual, and the beauty of bilingualism, ahead of publication of her book A Billion Balloons of Questions, which publishes next month on 16th June.

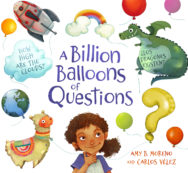

A Billion Balloons of Questions

By Amy B. Moreno, illustrated by Carlos Velez

Published by Floris Books

The Beauty of Bilingualism

The teetering stack of picture books beside the couch reminds me that we need to squeeze in another bookshelf. My children and I love reading books together in English, Spanish, and Scots, including side-by-side and traditional translations (my personal favourite is James Robertson’s Scots translation of Julia Donaldson’s The Gruffalo).

But it wasn’t easy to find children’s books showing the way we use our languages at home. The exceptions I found were I love Saturdays y Domingos by Alma Flor Ada; Margarita y Margaret by Lynn Reiser; Besos for Baby by Jen Arena; and, for Scots/English, the Thistle Street series by Mike Nicholson. These books use both languages to enhance the story, and the mixing style felt familiar. Outside of these, my children didn’t see themselves represented in many books. This was one of the reasons I wrote A Billion Balloons of Questions – a picture book about a little girl called Eva from a Scottish-Peruvian home who has lots and lots of questions.

The somewhat chaotic scene at the start of the book, when everyone is getting ready to leave the house in the morning, is brilliantly illustrated by Carlos Vélez. It will likely resonate with many parents of young children. In our case, I’ll be asking if they’ve brushed their teeth, while their dad asks “¿Dónde están tus zapatos?”

Like my own family, and Eva’s, the majority of families worldwide are bilingual. It might seem less prevalent in Scotland, but numbers increase when we take families using Scots and its dialects into account. We also have communities from all over the world, bringing their languages with them.

I speak Scottish English and Peruvian Spanish daily, and bits of Scots. In the Andes and some coastal regions, Peruvian Spanish includes many Quechua words, so they pepper our Spanish. I’ve been interested in languages and bilingualism for several years, particularly since becoming a parent.

In the 1950s, bilingualism was seen as a disadvantage as it was believed to cause delays in childhood language development. Families were encourage to use only the community language at home. Tragically, this caused children to lose their connection to their parents’ language, culture, and heritage. Fortunately this is no longer advised, and current research shows an array of benefits to being bilingual, and to language learning in general.

Any language learning exercises the area of the brain responsible for executive functioning, problem solving, task switching, and focus and it’s often noted that bilingual children tend to find it easier to pick up additional languages than their monolingual peers. However, the lack of representation of their language and culture in books and media can lead to children rejecting the home language, causing conflict and disconnection. Bilingual young people sometimes talk of feeling they belong to neither language or culture, rather than both.

Supporting bilingualism is crucial in allowing a child to connect with that side of their heritage and culture. If a child is unable to visit the homeland of their parent(s), speaking that language, reading stories, naming and eating their cultural foods, all weave in the links they would otherwise have missed out on. And, on a lighter note, bilingualism in children also leads to some funny mistakes and playing with language. My daughter, age two and a half, told me her favourite dog was a ‘sausage perro’. It also leads to interesting questions, like Eva in the book wondering if her abuelita’s dog barks in Spanish.

Bilingual families may mix or separate their languages in different ways. Many bilinguals ‘code switch’, flipping between languages – this mixing style is named ‘Spanglish’, ‘Chinglish’, ‘Franglais’, and so on. It is sometimes looked down upon and seen as ‘messy’. There is also valid concern about language conservation when the dominant language replaces words unnecessarily. However, there is an argument that this mixing is a natural part of the development of languages. That it could, in fact, be a way of preserving non-community languages. It is certainly the lived experience of many bilinguals and multilinguals.

In bilingual families, sometimes we ask a question in one language, and receive an answer in another. Other times, the concept may not exist in one language or translate well, so you get ‘este niñito es recontra cheeky’ (‘that wee boy is right cheeky’). I don’t think the words available in Spanish quite encapsulate ‘cheeky’ as naughty but also potentially funny. Other words translate surprisingly well – ‘recontra’ is a colloquial ‘really’ emphasis word.

Taking this language mixing one step further, I’ve even heard bilingual children conjugate a verb from one language based on the rules of another language. My favourite example was ‘Il m’a kické’ (‘He kicked me’). In French, the verb ‘to kick’ is long – donner un coup de pied, so the boy conjugated the English verb ‘to kick’ into French first person present tense, and made up a short-cut in the moment!

In A Billion Balloons of Questions, Eva’s family use a mixture of English and Spanish, in a way that reflects how we speak at home, and how bilingual children think and process language. In one scene, Eva is talking to her abuelita in Spanish by video call, but at the same time wondering ‘When will abuelita visit us?’. I think bilingual children’s creative use of two languages is fascinating – they are showing us, verbally, how the languages relate and connect in their brain. It seems like they don’t simply translate, but merge, link, and create new rules and combinations.

Parents and teachers play a vital role by supporting bilingual children to explore and share their language and culture, providing them with a safe space in which to make mistakes and to use their languages in ‘untraditional’ ways, such as ‘Spanglish’, if that feels authentic to them. Authors and illustrators let children recognise themselves and their languages in books, comics, and graphic novels. For me, it’s a great privilege to help my children, and other English-Spanish bilingual children see themselves represented in a picture book with A Billion Balloons of Questions. I hope, as families read it together, it helps instil pride in their language mix. There are so many ways we can celebrate and recognise the – at times messy – beauty of bilingualism.

A Billion Balloons of Questions by Amy Moreno, illustrated by Carlos Velez is published by Floris Books, priced £12.99.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

Modren Makars: Yin by Irene Howat, Ann MacKinnon & Finola Scott

Modren Makars: Yin by Irene Howat, Ann MacKinnon & Finola Scott

‘Ower excited, he waaks at crack o dawn, grabs farls fresh frae the fire, an awa til moon-rise.’

Uncle Pete and the Forest of Lost Things

Uncle Pete and the Forest of Lost Things

‘Along the way they encounter some scary, gigantic cats, a rogue tidal wave and other dangerous dile …