‘ McBey – an international Scot par excellence who lived in London, the US and Morocco – largely shunned the Establishment, and lived according to his own rules.’

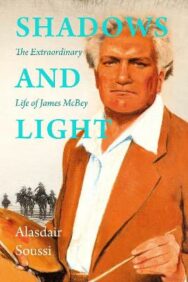

Creative genius, war artist, adventurer: these are just some of the descriptors attributed to Aberdeenshire-born painter and printmaker James McBey. Alasdair Soussi, author of the biography Shadows and Light, tells Books from Scotland about McBey how the creator’s work has come to mean so much to him.

Shadows and Light, The Extraordinary Life of James McBey

By Alasdair Soussi

Published by Scotland Street Press

As I stood over James McBey’s gravestone in Tangier, Morocco, during one parched afternoon earlier this year, I couldn’t help but think of the words the Scottish artist-adventurer had written to his American wife, Marguerite, some ten years before his death in 1959:

’If anything should happen, and if it be possible without much trouble, I should like to stay in the lower property, on the high bit, just beneath the Cherifian Garden. It is still, to me, a heaven down there.’

Today, on Cherifian Rocks, a steep tract of 30 acres which twists its way down to the ocean through sprawling woodland and brushland, one can still experience the reverent silence which has cocooned McBey’s place of rest for more than 60 years. The land, once owned by the McBeys themselves, but for many years now under the ownership of the American School of Tangier, enjoys views over the Straits of Gibraltar, and, just as in the artist’s time, remains impervious to the hustle and bustle of the city.

For me, as his biographer, visiting McBey’s graveside was a pilgrimage, a chance to pay homage to one of the greatest – and today most underrated – artists in Scottish, British and European history. But while he ended his life amid the sun-kissed surrounds of north-western Morocco – he began it in 1883 as the illegitimate son of a blacksmith’s daughter in Foveran, Aberdeenshire, on the edges of the icy North Sea. His was not a young life spent in grinding poverty, but neither was it one filled with riches, all-consuming love and emotional stability: he endured an uneasy relationship with his mother, who forced him to give up school at 13 to begin work as a bank clerk, and who, going prematurely blind and suffering mental health issues, tragically hanged herself in the basement of their Aberdeen tenement. As a child, he met his father only once – and, lacking any kind of emotional support from his parents, found it with his maternal grandmother whom he cherished.

McBey’s bleak beginnings were to haunt him for the rest of his days – but it would also set him on a path to independence that would become the hallmark of a stellar artistic career. Yet it was McBey the man – his eventual severing of ties with a banking trade he had come to loathe, his largely self-taught status as an artist, his decision to leave Aberdeen for the bright lights of London and his global adventures – which first compelled me to document his extraordinary story. But it was his art – and particularly his etchings in which he was regarded as a bona fide genius – that gained him celebrity status on both sides of the Atlantic during the inter-war years.

Indeed, McBey’s many prints, watercolours and oils, from his travels in the Arabic-speaking world, the US, Europe and elsewhere hang in museums worldwide. In London’s Imperial War Museum is his portrait of a gaunt and exhausted T. E. Lawrence (aka Lawrence of Arabia) whom he painted in war-torn Damascus during his swashbuckling stint as Britain’s official war artist in the Middle East during World War I. In the US the Cummer Museum of Art & Gardens in Florida, just one of several museums in America which honour McBey, boasts one of the largest collections of his work outside Scotland. Among the McBeys on display at the Tangier American Legation Museum in Morocco is his hypnotic oil painting of Zohra, his domestic servant in Tangier during the early 1950s, which is widely-known as the ‘Moroccan Mona Lisa’. And at Aberdeen Art Gallery, the Scotsman’s spiritual home, which hosts the world’s largest archive of his work, one can visit its McBey Gallery and enjoy a taste of the man once celebrated as the printmaking heir to Rembrandt and Whistler.

McBey – an international Scot par excellence who lived in London, the US and Morocco – largely shunned the Establishment, and lived according to his own rules. As one of his (many) lovers suggested in a poem, McBey’s propensity for good fortune (and success) was almost heaven-sent:

The wonder grows from day to day

How God can look after James McBey

When as the Bible says he oughter

He casts his bread upon the water

Lo! It returns upon the tide

Well buttered on the other side

When servants leave him is he stranded?

No God is much too open handed –

He takes two angels from the Host

And sends them via The Morning Post

No wonder France is still in debt

And baulked the Balkans fume and fret,

And trade is in a dreadful plight –

God has no time to put things right:

He’s far too busy, night and day,

In doing things for James McBey

Shadows and Light, The Extraordinary Life of James McBey by Alasdair Soussi is published by Scotland Street Press, priced £29.99. It will also be the subject of an exhibition at Aberdeen Art Gallery between February and May 2023.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

The Book…According to Ever Dundas

The Book…According to Ever Dundas

‘I want readers to be swept up in the story, so I hope I’ve achieved that.’