‘When he returned to school after the holidays, he listed retrenchment and reinstatement among the new words he had learnt during the Christmas break.’

In the much-anticipated second novel from Ayòbámi Adébáyò, we follow the lives of Ẹniọlá and Wuraola, two people from different backgrounds whose lives come together as they are impacted by the political changes in Nigeria at the turn of the millenium. We introduce you to Ẹniọlá in this extract.

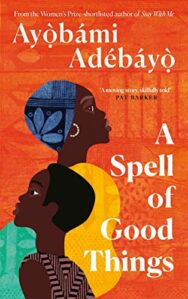

A Spell of Good Things

By Ayòbámi Adébáyò

Published by Canongate Books

It did not make a difference if Ẹniọlá reminded her that their classrooms were not even in the same building. His mother would still make him wait for Bùsọ́lá before leaving home. She wanted them to walk to and from Glorious Destiny Comprehensive Secondary School together every single day when possible and had even forced Ẹniọlá to promise that he would always follow his younger sister to her desk before going to his classroom.

On most mornings, as they approached the first school building, their white socks already coated with red dust from what was not even a ten-minute walk, Ẹniọlá often thought about the secondary school his father had promised Ẹniọlá would attend. He was sure there was no red dust on the way to that school. It probably had pavements, walkways and grassy lanes leading from its hostels to its laboratories and classrooms.

Ẹniọlá was nine when his father made that promise. He could not imagine then that anything would cause him to end up in this stupid Glorious Destiny school. He had been in primary five at the time, and all his classmates were preparing to write common entrance examinations. Meanwhile, his father insisted that, since the primary school system was designed to go all the way up to primary six, Ẹniọlá must move on to that class instead of secondary school like most of his classmates.

Ẹniọlá had spent weeks thinking about how he could convince his parents that he was ready for secondary school. He was taller than most of the JSS1 students he ran into on his way to and from his primary school, and he always scored higher than at least half of his classmates in tests and exams. He had memorised all the conversions and tables on the back of his Olympic Exercise Book and could recite the times table from one times one, which equalled one, through twelve times twelve, which equalled one hundred and forty-four, all the way to fourteen times fourteen, which was one hundred and ninety-six. During the weeks that led up to his ninth birthday, Ẹniọlá swept the living room before his mother got to it in the mornings, stopped complaining about not being allowed to go outside and play football with their neighbour’s children when he was asked to watch Bùsọ́ lá, and since he wasn’t tall enough to wash the whole car, spent his Saturday mornings scrubbing the tires of his father’s blue Volkswagen Beetle. Worried that all his goodness would go unnoticed by his parents, even as he suspected that he might be close to qualifying for sainthood, one Sunday on the way to Mass, Ẹniọlá announced that he wanted to become an altar boy. He was relieved when his mother said she would not allow it because it might distract him from his studies. Throughout that week, he lied often about how much he wanted to be an altar boy, making a good impression on his father, who thought such intense desire showed he was growing up in the fear of the Lord.

…

After his father’s promise, it was easier for him to listen as his classmates bragged about secondary school. He could also tell them about how he would attend a Federal Unity school. A year after they all went off to secondary school, yes. But was any of them even going to a boarding school? A Unity school? Ẹniọlá found a way to bring up the Unity school almost every day, retelling the stories Collins had shared with him until he could see that some of his friends had become jealous. Their envy was a comfort as they wrote their common entrance exams and went away to different schools, while he was left behind to complete primary six with two boys who had failed every common entrance exam they wrote. He was going to be like Collins soon. He too would return home thrice a year, and other boys in the neighbourhood would gather around him as he told stories of all he had been up to without his parents monitoring him. He thought about this every day as he walked to and from school alone. The friends he used to make the trip with were no longer his schoolmates, and though he missed them, it did not matter. He was going to be like Collins soon. That would make up for everything; all he had to do was wait.

And then, at the end of his first term in primary six, just a couple of weeks before Christmas, his father and over four thousand teachers in the state were sacked. At first, everything at home went on as usual. His father continued to leave the house at seven in the morning on weekdays, tie knotted, hair shining where globs of Morgan’s Pomade had not been combed in thoroughly, side parting still in place. Ẹniọlá went on believing he would still proceed to the Unity school in Ìkìrun as planned. After all, it was only a matter of time before the governor realised that he was destroying public schools and all the teachers would be reinstated with a personal apology from him. At the very least, some teachers had to be reinstated, and Ẹniọlá’s father, with his experience and qualifications, would definitely be one of those who would be called back because they were needed. It had to happen soon. How would the school run its syllabus without history? How? Night after night, Ẹniọlá fell asleep next to Bùsọ́lá on the sofa while their parents continued this conversation instead of saying the bedtime prayers.

On the radio, one of the governor’s aides explained that most of the teachers who had been retrenched taught subjects—fine arts, Yorùbá, food and nutrition, Islamic and Christian religious studies—that would do nothing for the nation’s development.

What will our children do with Yorùbá in this modern age? What? You see, what we need now is technology, science and technology. And how will watercolours be useful to them? Isn’t that what the fine arts teachers teach them about? Watercolour.

The man on the radio laughed.

Christmas had come and gone. It was the first day of the new year, and some of his parents’ friends, many of whom had also lost their jobs, had come over for dinner. As the man continued to laugh, Ẹniọlá found that although the bowl in front of him was filled with pepper soup, he could no longer feel the sting from the peppers or taste the meat. He felt as though he was drinking water with a spoon. When he returned to school after the holidays, he listed retrenchment and reinstatement among the new words he had learnt during the Christmas break.

A Spell of Good Things by Ayòbámi Adébáyò is published by Canongate Books, priced £18.99.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

David Robinson Reviews: Elixir by Kapka Kassabova

David Robinson Reviews: Elixir by Kapka Kassabova

‘Somehow, in an alchemical process that involves stirring together vast knowledge of plants, history …

The Rymour Effect: Showcasing Glasgow Scots

The Rymour Effect: Showcasing Glasgow Scots

‘There’s wan shinin light though, ma young grandson. Twinty years auld he is, a strappin big lad. Ma …