‘Whit am I gaunny dae like? Trail round the charity shops for tae get some crap tae resell on eBay, get a few quid in ma PayPal account’

It’s September 2014 and Mickey Bell is in crisis. He has HIV, is on the dole, and dwells in the high flats in Drumkirk. Unsure of where his life is heading, will he be able to turn things around and look towards a brighter future?

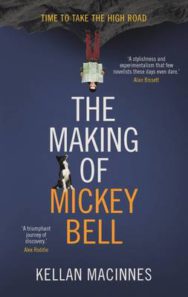

The Making of Mickey Bell

By Kellan MacInnes

Published by Sandstone Press

He’d been in the huddle of people crowded round the Reduced shelf of the chiller cabinet in the Morrisons on the corner of the Crow Road, trying to see the prices on the yellow stickers on plastic packs of mince, paper bags of mini beef pasties, tubs of cottage cheese and grey-looking lamb chops.

The old guy in the woolly hat was there of course.

He must live in the supermarket.

He’s there every time Mickey goes in, standing chatting to the staff as they fill the shelves with bags of wild rocket and spinach, cartons of cherry tomatoes and cellophane packets of beansprouts. He overheard him asking the woman stacking the shelves in aisle one with red-stickered Two for £5 ready meals, what time she finished at. Then he felt guilty, silently chastised himself, thinking of the old man’s cold, empty flat, his loneliness showing through in the endless, empty days spent pacing the aisles of the supermarket.

When they sat in rows in school on plastic chairs at metal-framed desks with Formica tops and looked at books, the pages were full of pictures of what people did. Pictures of firemen, postmen, dustbin men, nurses, bus drivers, teachers and airline pilots. There was a sense back then the children could be anything they wanted. No pictures in the books of childhood of people jostling round a chiller cabinet in a supermarket aisle scrabbling to buy yellow-stickered, reduced-to-clear food items.

MICKEY: I’m one o’ the lucky ones but. I know I am. I know that fine. ‘Your HIV’s very stable,’ ma doctor at the clinic told me last week. My GP’s the same: CD4 count in the low hundreds – below average but nothing tae worry about, she says. My life’s been saved by twenty-first-century medical science. The meds and the NHS and all that wis there for me when I needed it. But sometimes I get tae thinkin’ like whit’s the fuckin point? WHAT IS THE FUCKIN POINT? It all seems kindae lacking in meaning sometimes.

I mean – whit am I on the fuckin planet for but?

Tae lie in my bed wanking and fartin’ till three o’clock in the fuckin afternoon?

I dinnae think so.

Some mornings jist in case the DSS are watchin’ like, I’ll get up early and open the blinds and then go back tae bed.

Ha ha ha!

That’s a joke – right?

OK, so I’ll get up then. Whit am I gaunny dae like? Trail round the charity shops for tae get some crap tae resell on eBay, get a few quid in ma PayPal account. I’ll be fuckin minted then like, aye right – then stay up all night talkin’ tae folk in America and makin’ non-friends on fuckin shite Facebook. Fuckin pointless but! Whit the fuck am I daein’ with my life that I’m taking fuckin six tablets a day to keep alive? Maybe I should jist have a wank in the bath wi’ a polybag over ma heid and fuckin be done wi’ it. That’s what I think – sometimes – in the long afternoons on the dole as the rain pours down on Drumkirk.

Outside the supermarket, he waited at the bus stop in Great Western Road. It was a hot day in the city and a balding long-haired man in filthy combat trousers and a worn leather jacket pedalled slowly by on a racing bike.

Across the street he watched a bare-chested, young guy with tattoos and white trainers and an inch of stripey boxer shorts visible above the waistband of his jeans, being dragged along the pavement by a huge Alsatian on a chain lead.

MICKEY: Scottish people go fuckin mental when the temperature rises – it’s like the weather triggers something and they go back in time tae when Scotland wis near the equator and there were palm trees in Motherwell and fuckin dinosaurs in Fife.

Aw fuck. The bus pass routine: hold yer national entitlement card in front of Perspex screen protecting driver. It saves a fuckin fortune in bus fares – be stuck in the flat all day without it but never run for the bus mind. You’re supposed tae be disabled but. That’s why I’ve got a bus pass – right? The driver’s looking at me. He’s thinkin’ I’ve seen him oot walking his dug. He’s no disabled. He’s no in a wheelchair. How come he’s got a bus pass? Now walk slowly upstairs and sit down in the front seats where you used tae sit tae drive the bus when you were a kid. Sunlight shining on faded fabric seats. Dust specks floating in the air. Then get up again and open all the windows on the empty top deck of the bus.

The sun was beating off the pavements in Douglas Street in the centre of Milngavie when he stepped down from the bus in a haze of hot diesel exhaust and hissing air brakes. He stood, watching as the bus pulled away and, orange indicators flashing, turned right into Campbell Avenue.

He looked around at the 1930s bungalows, each one white-painted and well maintained, the gardens with lawns cut and hedges trimmed. A blue hydrangea flowered on a striped lawn among lazily swaying clumps of pampas grass.

Only three miles but it was a long, long way from the dandelions and knee-high grass littered with crisp packets, polystyrene fast-food cartons, Coke cans, empty torpedoes of cider and dirty plastic syringes choking the abandoned front gardens of Drumkirk.

He wandered along Craigdhu Road.

A woman walking a golden retriever passed him. ‘Good morning!’

He smiled back at her.

Nae Staffies and Rottweilers and guys wi’ biro tattoos here then.

Craigdhu Road broadened out into a wide semi-pedestrianised street. He walked past RS McColls, the British Heart Foundation shop and Costa Coffee. None of the shop windows were boarded up. And there was a Greggs. Mickey hadn’t eaten that day and he headed straight for the shop with its inviting smell of lentil soup and pastry.

A black Labrador-like dog with strange orange highlights in its thick, curly coat was tied to a park bench outside Greggs. The dog watched him disappear through the glass doors of the baker’s. The dog remained in a sitting position for about sixty seconds then its front legs slid slowly forward and it lay down, head resting flat on the pavement, staring at the door of the shop.

Five minutes later the dog wagged its tail as Mickey reappeared clutching a paper cup of soup and a steak slice and a sausage roll in a white paper bag already turning translucent with yellow grease. He sat down on the bench and tore a corner of pastry off the steak slice and dropped it at the dog’s paws.

A grey-haired man in walking boots and a red North Face T-shirt came across and made a fuss of the dog. It rolled on its back, wriggling and wagging its tail.

‘What kindae dog is he, pal?’ asked Mickey through a mouthful of sausage roll.

‘Labrador crossed with a poodle,’

The man rubbed the dog’s tummy.

‘Great dog,’said Mickey and he watched as the man picked up a large, heavy-looking rucksack and a pair of walking poles and, with the dog following at his heel, walked away, past the bench where Mickey was sitting.

Mickey looked round. Behind him a paved path led into the trees and above his head, spanning the gap between the brick buildings, was a steel archway. He twisted his head round to read the words on it.

When he’d finished licking the last flakes of puff pastry from his fingers, he got up from the bench and stepped through the archway.

And then everything was different.

The Making of Mickey Bell by Kellan MacInnes is out now (PB, £8.99) published by Sandstone Press.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

A Happy Little Island

A Happy Little Island

‘The scribe needed a piece of dry land to anchor his story and so he wrote in a skerry in the sea’